Field Experiments

FC: Will you share with us a bit about Field Experiments, for those who don’t know—How did the three of you band together? Where were you each coming from? What are your objectives? Where do you see it all going?

FE: We are a nomadic design collective that explores traditional crafts by engaging in collaborative making with local craftspeople in diverse regions around the world. Underpinned by cross-cultural exchange, we produce projects, products, and ideas across multiple formats including furniture, clothing, video works, publications, exhibitions, interiors, installations and printed materials.

We come from various backgrounds and places but all met in 2009 while working with Stefan Sagmeister on his yearlong sabbatical. Paul is a Melbourne-based graphic designer and runs a studio called U-P, Karim is from Montreal and works around the world as a designer and commercial director, and Benjamin is an event and production designer working out of New York.

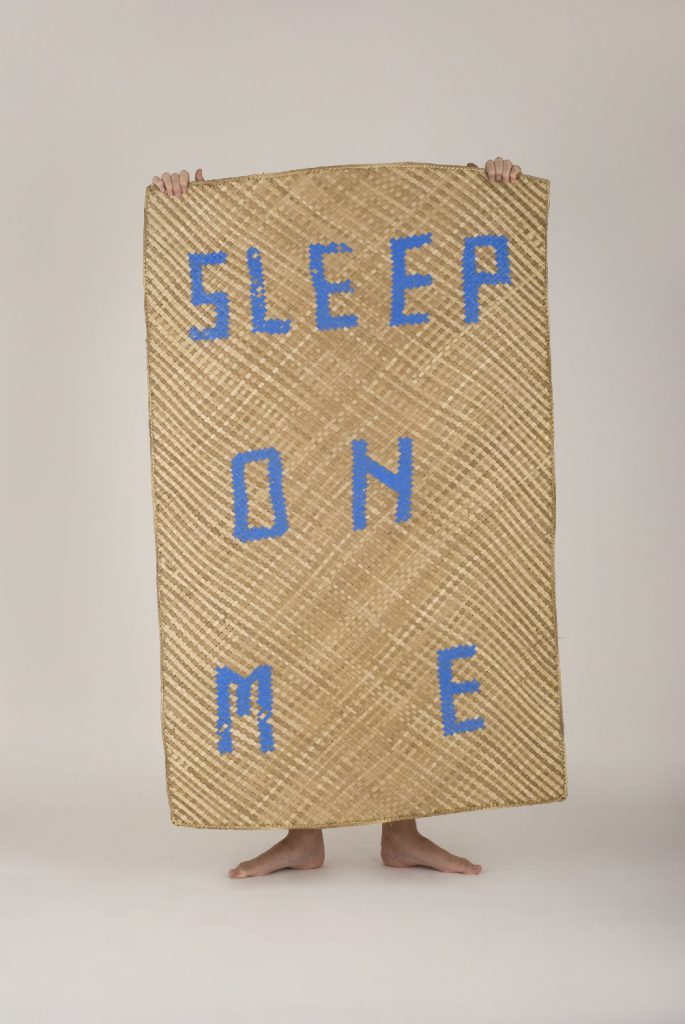

The inaugural Field Experiments project was conducted over three months in Bali Indonesia. From June-September 2013, we set up a studio and home in Lodtunduh, a farming community situated on the outskirts of Ubud. We collaborated together and conducted daily experiments in stone masonry, wood carving, batik, painting, basket weaving and kite-making with local craftspeople. The project explored the re-assemblage of cultural craft objects in a tourist-driven economy. It resulted in the making of more than 100 one-off objects that examine the influence of transnational exchange in the making process. We wanted to propose how a souvenir can manifest and encourage cross-cultural learning and understanding.

Although many of the creations are happily nothing more than ideas or expressions, a selection of objects become prototypes for future products. Our goal was to bring new credence to the concept of "Made in Bali," highlighting the skill and ingenuity of the Balinese people, to foster a renewed appreciation for Balinese craft and culture. We were committed to giving back more than we had taken from the Balinese and we hope to inspire a more responsible traveler, one that has a deeper thirst to interact with the Balinese people and their culture, ultimately creating a new platform for the economy of Balinese craft makers that extends well beyond the life of this one project. This model perfectly exemplifies how we envision moving forward with Field Experiments in other places.

FC: A big part of the concept for your projects is the process of on-site design research done abroad with local designers and craftspeople. How do you choose the site? You’ve worked extensively in Indonesia… where else? What are some of your dream sites?

FE: Collectively we’ve spent two years in Bali building relationships with local craftspeople, observing and participating in Balinese culture, and creating propositional work. Removing ourselves from our respective environments in Melbourne, Montreal, and New York, was an important first step, and proved that a simple relocation immediately encourages new perspectives on creating. In our cities, design is fast and industrial. It is consumed around-the-clock on blogs, social media, and in galleries, shops, books and magazines. While working at home, we notice we are working with our hands less and less and are increasingly disconnected with the makers of our work. By breaking away from the overwhelming speed of design consumption and by setting up a studio together in a more tranquil setting, the intention was to slow time and create some much needed breathing space to contemplate ideas and create.

As for future sites—there are just too many! We have set our eyes on Athens, Greece for 2016 and think it will be a dynamic place to be able to dive back into an ancient culture and yet today is experiencing a defining and critical role in the EU.

FC: Can you talk about souvenirs? It’s a really interesting phenomenon in general, and you are using it in an unusual way. My understanding of a souvenir is that it’s specific to a time, place, or event, and the driving force to buy a souvenir is that you can only get it in that place and moment. It serves as a reminder… there’s a certain nostalgic quality to souvenirs, and typically a kitschiness. Field Experiments does a lot to evolve the meaning of souvenir. What are some of the principles behind this?

FE: While working in Bali the souvenir emerged as a central concept, linking our interests in travel, design, everyday objects, craft, and culture. Souvenirs are an important part of any tourist economy and are traditionally small mementos. Typically they are mass-produced and sold by middlemen in gift shops and markets. In Bali, the souvenir market is often associated with the degradation of authentic local art and craft, as more and more artists and makers dedicate their creativity into the creation of these commercial objects.

FC: Do you want to talk a little bit about tourism as well, and the tourist’s typical relationship to the souvenir? Is your work trying to subvert expectations in a more commonplace tourist/local craftsperson/souvenir relationship?

FE: Field Experiments considered the souvenir with a new optimism. The project challenged the conventional notion of a souvenir and presented a new opportunity for what a souvenir could be. By working directly with the local craft communities and by creating a collection of one-off objects infused with a story of Balinese life, the project explored how an object could become more deeply connected to a place.

It’s a tragedy that tourists come with preconceived ideas of a place and what that place has to offer—a souvenir is just one area where objects get caught up in that same expectation. So why not flip it on its head and challenge why American bald eagles are being carved in Indonesia. Finding a contemporary voice for a souvenir is part of the challenge.

FC: You often work closely with local craftspeople, which must be incredible—especially in such remote places, where the design isn’t typically influenced by global trends, but rather a kind of ingenuity that develops over generations and is usually based on particular resources and needs. How do you connect with these people? Will you tell us about some of these individuals? What is your relationship like with them?

FE: It is quite simple—we are looking for things that speak to us, diving into the local vernacular, whether it is a material or a technique. Something always stands out to us and informs our process. Once we define what that is, we stop by local studios or workshops and ask if they are interested in collaborating with us. Not all relationships work out, but having more than a few days in a location really helps them see that you are not stopping by for a quick fix. In Bali, we worked closely with about nine artisans and they all became such dynamic partners, far beyond any vendor relationships we have in our respective cities.

One relationship that particularly stands out to us is a husband and wife, Bapak Agung and Ibu Antik, that run a batik workshop in the old village of Pejeng. They collaborated with us to create experiment 066 - 070. We supplied them with tailored temple shirts and asked them to use these as rags to wipe their wax tools, while chanting other works. The shirts were then dip dyed in natural indigo.

Their workshop is a reminder of the ingenuity and communal spirit of the Balinese people. They used the downtime after the Kuta bombings, when the economy was suffering, to study batik making. Agung travelled to Jogyakarta to master the craft at the Balai Pelatihan Batik. When the economy began to recover and tourists started to return, they mobilized and established their unique batik workshop fusing his knowledge gained from Jogyakarta with self-teachings on natural dye (their workshop is the only one in Bali using natural dyes). Agung brought indigo plants from Thailand to complement the limited supply of foraged wild indigo found on the east coast only during rainy season. They distributed the plants out to the villagers to grow and now buy them back from community-managed plantations. Agung and Antik only employ women from Pejeng, which allows them to remain close to their families. Keeping the traditions of the village protected, they provide all staff with two paid days off per year for fulfilling temple duties. This is extraordinary for Bali—typically for any amount of time a worker is not producing, they are not paid at all.

Agung and Antik never take on private commissions. Agung firmly believes this is a distraction that takes away from their own creative direction. We took a daylong batik workshop with Antik and she became curious of our experimental approach, commenting that our creative spirit mirrored that of her young husband. After many lengthy discussions she convinced Agung to take on our work and he now agrees that both sides had a lot to learn from this creative exchange.

FC: Will you elaborate on the kinds of cross-cultural exchange that are happening in your process? I love the idea of having a conversation through design objects, since design is so personal and expressive of particular wants or needs, as well as experience. Obviously your perspectives are quite different from one another, each of you coming from Montreal, Melbourne, and New York, but then those varying perspectives are compounded by the differences with the local craftspeople you are working with. How do you reconcile these differences? What are some valuable lessons you have learned?

FE: Between the three of us it is quite amazing to have different perspectives and yet completely trust in each other—we have always been this way and it must come from the fact that we met on such common ground. Operating as a collective allows for there to be anonymous authorship and no one is held to a specific piece. We all have a concrete understanding to make sure we push each other into unseen directions and territories and actually allow for them to affect our outcomes. Having three in a collective is challenging but also incredibly fun—it’s easy to have two of us gang together and really push the third.

It’s all one big experiment and we are continually evolving.

FC: Will you also tell us about the economics of your studio—does a percentage of the sales for some of these objects go back to the craftspeople you collaborated with?

FE: The day we find a way to make some profit from all this will be the day we find a way to give back. Field Experiments has been funded by our separate design practices. We are far from a studio or business that has a steady income. Part of us wants to keep it unconnected to the world of commerce or at least beyond our little online shop. But we also want to continuously grow.

To be honest, we see working with them and sharing their story as the most honest route to sustaining their craft and livelihood. The reality of it all, is that we have a lot to learn from them—in our eyes, they are living a desirable life of simply supporting their families through their craft, and they are happy. That's all were are looking for too.

FC: So you’ve all been working at Otis in LA this week, extending your design practice out to students. Is pedagogy something you see fitting into the Field Experiments conversation moving forward?

FE: Teaching is a great way to share our experiences and stories beyond making objects. This year, we all made a clear decision to teach more and seek out these opportunities. This is something we all have done individually in the past but not as a team of three and it is much more exciting teaching as a collective. We are exploring ways to have friends and students join in on our projects around the world and so any opportunity to have a workshop or teach in this capacity is something we will say yes to. It’s a great way to give back and share all that we are so lucky to see in the world.

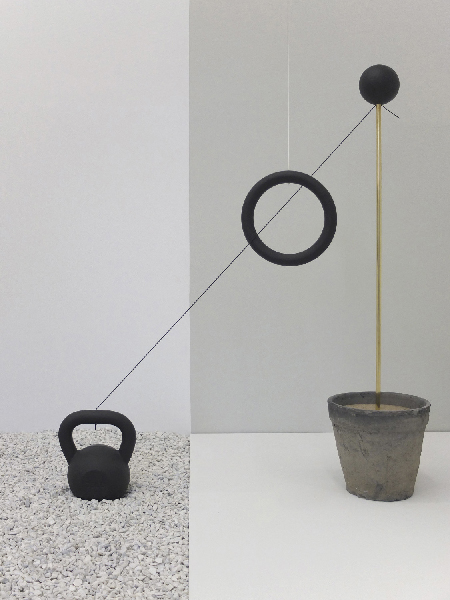

FC: Much of your work does a fine job at dancing the line between design object and art object, but design typically comes first. That is, though the objects could stand alone and be regarded, one could also immediately imagine how the object might be used. This new show at Moiety is more enigmatic—the work suggests function, but tilts towards formal qualities. The inspiration for the show was playgrounds, which are often abstract landscapes. The design of a playground might suggests how one could play, but the play itself stems in the imagination and the playground primarily serves as a site for play. In this case, the play happens mainly in the imagination, as the eye jumps or swings from one form to the next. Where did these forms come from? Do you see them as sculptures, design objects, both?

FE: Grounds for Play, was part of a continued study into the process of play for making and thinking. Springing from a five-year photographic documentation of the New York City playground, it explored the materials, shapes, structures and spaces that signify play.

The show was a very small lens into one place and time that we all thought was worth investigating on a deeper level. We find pleasure in making functional things or at least things that juxtapose a function, but it's also very satisfying to let it be open-ended and not have a definitive outcome. Yet, keeping something open-ended is hard for us as we are all trained in some form of design problem-solving. Seeing that this was a gallery atmosphere, we felt we could cut loose and let the forms do just that—suggest a function. We like to keep things at a tangible level to a person that is far from savvy with the art world and we would rather keep it accessible to the common eye.

FC: The "NO ENGAGING IN COMMERCIAL ACTIVITY" etched metal slab really caught my eye, and it’s the only text-based work in the show. The type tilts and slips out of place in a manner that behaves [playfully] in concert with the rest of the work. Will you unpack this piece for us?

FE: This piece is inspired by the list of rules that govern New York City playgrounds. Removing things from their context, whether that is objects or words, is something we're continuously exploring. We are exploring the same themes of tension and movement as the other displayed pieces but through type, not objects.