Memphis group

Text by Claudia Eve Beauchesne

Photography by Dennis Zanone, Thanh Truc Trinh & Courtesy of Memphis-Milano.org

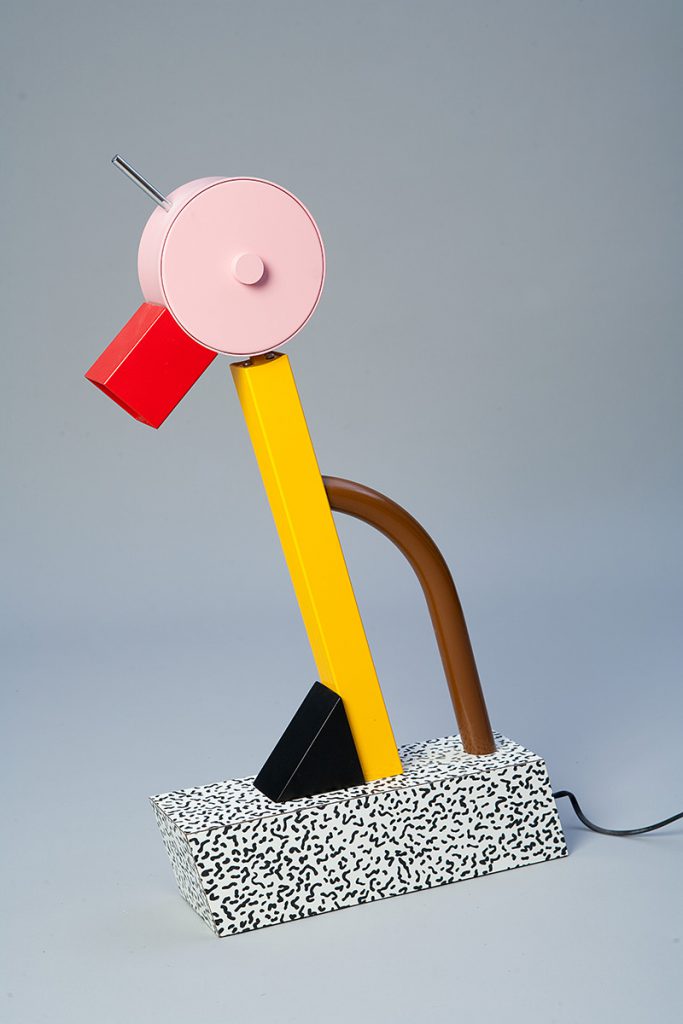

Memphis was a groundbreaking and influential design collective founded in Milan in the early 1980s around the celebrated architect and designer Ettore Sottsass. Its large cast of international designers shared a common attitude that could accommodate each designer’s unique set of cultural references while remaining cohesive. Between 1981 and 1987, the group produced seven collections of instantly recognizable furniture and housewares that soon became icons of postmodern design, combining bold geometric forms, bright colors, and hyperkinetic patterns. Memphis was so of-the-moment that the striking look of its anthropomorphic bookcases, oversized chairs and toylike lamps was quickly perceived as dated, perhaps a sign that the group had succeeded in creating objects that had the same immediacy as snapshots. Now, almost thirty years after the ephemeral movement ended, Memphis has been rediscovered and reinterpreted by young designers and artists.

Born in Austria in 1917, Ettore Sottsass Jr. grew up in Milan and was trained as an architect, but became a prolific product designer and cultural theorist. He first made his mark on the design world in the 1960s when he designed a series of lightweight portable typewriters for the Italian firm Olivetti. Sottsass saw electronics as mysterious, futuristic objects, and wanted to show that they could be more than purely utilitarian tools for secretaries with humdrum lives. In 1969, he designed the Valentine typewriter, whose sleek, bright red plastic case set it apart from the bulky, greige office equipment of the time. Evocative and sexy, the Valentine boldly questioned the validity of the modernist approach to product design.

Modern design (exemplified by the work of the Bauhaus school, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, among others) attempted to (re)form the world in accordance with a strictly rational, utopic model. For modernists, form must follow function, so purity of intent is essential, hybrids must be avoided, and designs need to lend themselves to cost-efficient, democratic mass-production methods. As a result, modern furniture is simple, symmetrical and unadorned, usually done in neutral shades with an occasional pop of color intended to draw attention to the piece’s functional structure. Sottsass felt that design should reflect the fact that humans experience the world through their senses before they can order and intellectualize it. He wanted not to overthrow modernism, but to go beyond it; to approach function like a sociologist rather than like an engineer in order to explore the potential impact of a richer design language.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Sottsass traveled to India, where he was inspired by the geometric shapes and bright colors of the buildings. He also studied Asian traditions, as well as the bold architecture and design of the American suburbs, which celebrated technological progress and consumer culture with day-glo colors and dynamic forms referencing cars, exotic destinations and space travel. These new inspirations would soon inform his designs, and eventually become part of the Memphis aesthetic.

In 1977, Sottsass joined the experimental Milanese design collective Studio Alchimia, which was part of a larger movement of Italian designers intent on coming up with strategies to dismantle the rigid ideology of modernism—they called their alternative “Nuovo Design.” Alchimia’s furniture, housewares and decorative objects borrowed the colors and design vocabulary of the 1950s to explore the idea of banality and kitsch in everyday life. The pieces were functional but featured seemingly arbitrary decorative elements meant to stimulate the senses and rouse the imagination. They offered riddles rather than sensible design solutions.

More like an art movement than a design studio, Alchimia organized exhibitions, issued manifestos and took part in demonstrations. Its unique, handcrafted pieces were made to spark debates, not to sell. Sottsass felt that, in an industrial society, the most effective way to remain culturally relevant was to engage with the market by making products to be sold in stores, not put on a pedestal. He wanted to develop a commercial business model for these innovative designs. In the fall of 1980, he left Alchimia to concentrate on a new initiative: Memphis.

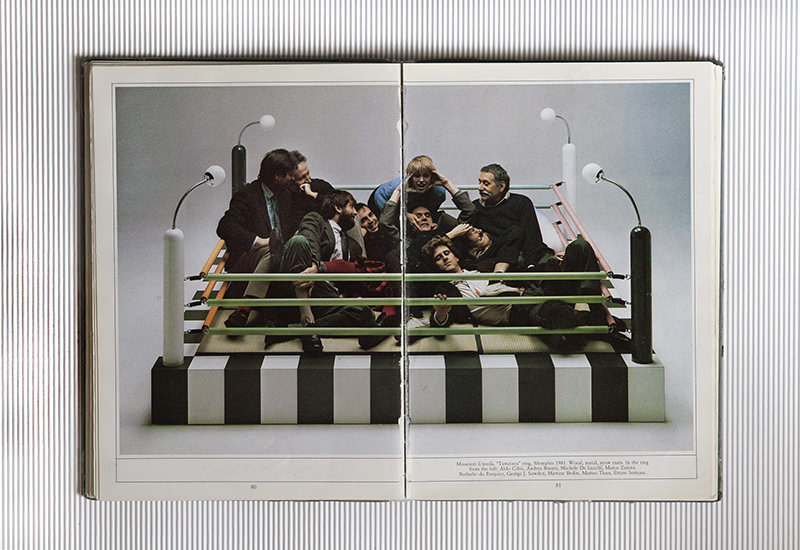

Sottsass had been invited by the owners of the Arc ’74 showroom to design a collection for the 1981 Milan Furniture Fair. Instead of working alone, he suggested the idea of a collective project involving some of the young protégés with whom he had recently founded an architecture firm. In November 1980, he gathered his business partners Marco Zanini, Aldo Cibic and Matteo Thun, as well as Michele De Lucchi and Martine Bedin, at his apartment to discuss the new venture. With them was Barbara Radice, a design critic who would become the group’s spokesperson and Sottsass’ wife.

Sottsass was 63 years old at the time, but all of his collaborators were in their twenties, some of them still students or freshly out of architecture school. Sottsass chose to work with younger designers because he found them more honest and sensitive, and wanted to help kickstart their career: “When I was young, nobody gave me any work opportunities,” he explained in 1988. “I knew I could have done outstanding things... I have always remembered that.”

As the group fleshed out their project, Bob Dylan’s single, “Stuck Outside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” was playing on the turntable. After hearing the song many times in a row, Sottsass suggested calling the new venture “Memphis” as a reference to both the birthplace of Elvis Presley and the ancient capital of Egypt’s Old Kingdom. It was an aptly strange combination of ancient history and popular culture, made even more intriguing by the fact that the group was based in Italy. At the next meeting, the British designer George Sowden and the French illustrator Nathalie Du Pasquier were invited to join the group. Together, this small team of like-minded designers developed the Memphis ethos.

In the following months, Sottsass invited several architects and designers whose work had affinities with the Memphis sensibility to suggest designs for the first collection. Among them were the Californian artist Peter Shire (who made teapots that Sottsass found “fresh, witty, and full of information for the future.”), the Spanish cartoonist and product designer Javier Mariscal, the Japanese designers Arata Isozaki, Shiro Kuramata and Masanori Umeda, and the world-renowned American architect Michael Graves. Memphis became a large, international collective of emerging talents and “big names” supported by Ernesto Gismondi, the founder of the Italian company Artemide, who agreed to manufacture and distribute the group’s designs.

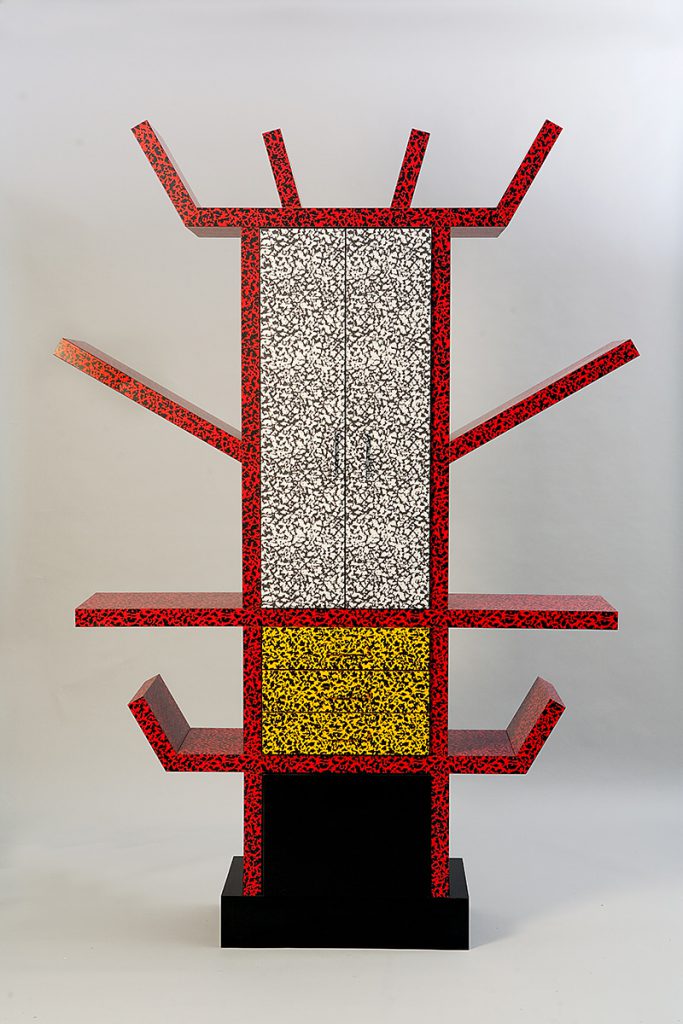

The first Memphis collection was launched in September 1981 at the Arc ’74 showroom during the Milan Furniture Fair. It included 55 undeniably innovative pieces (furniture, lamps, clocks and ceramics) that bore the names of luxury hotels and exotic destinations, like the Tahiti lamp, Fuji cabinets, Brazil table and Riviera chair. Although over twenty international designers had contributed pieces, the collection had an impressive stylistic unity, in part because Sottsass reviewed every proposal, but also because each designer brought his or her own culturally-specific influences to the mix.

The packed opening party and hip, international designers proved irresistible to the mass media, and although reactions from the press were far from unanimously favorable, the polarizing new style did not leave anyone indifferent. Barbara Radice soon published a series of articles celebrating Memphis as a groundbreaking new movement, and Sottsass’ friend, the fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld, had his Monte Carlo apartment furnished with Memphis pieces, sparking another stream of press coverage. Memphis became the world’s most popular avant-garde movement.

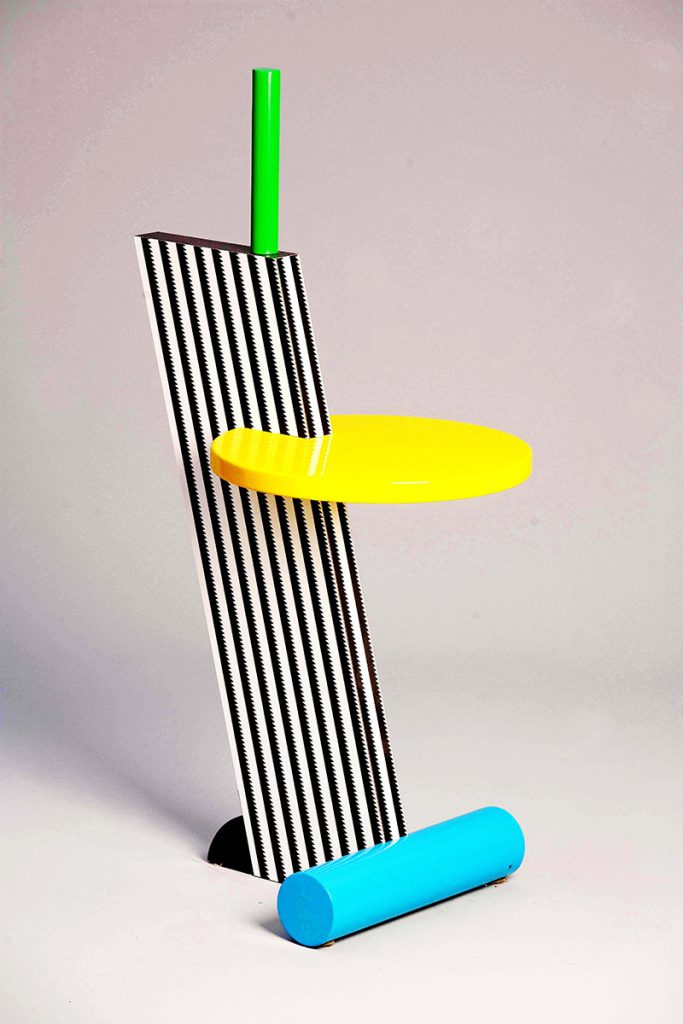

Memphis designs raise questions but refuse to answer them. Instead of building objects around a pre-determined structure, the group deconstructed both the objects and the structure in order to explore the ways in which they can communicate meaning. This intentionally nebulous ideology allows for a variety of interpretations.

It seems that one of the group’s main goals was to create products that merge structure and decoration, giving a physical form to abstract ideas and provoking an emotional response. Sottsass saw objects as physical manifestations of their designers’ worldview, and of the relation between an individual and society. In this optic, a new interpretation of the potential of life would inevitably lead to a new kind of design, which might itself inspire a new way of looking at the world. Memphis wanted to blur the lines between subject and object, to make objects that could potentially choose their own users, fostering a reciprocal relationship between people and their belongings.

Memphis designs also appear to be critiquing social hierarchies and the (often capitalist) power structures on which those hierarchies rely. The Memphis designers were keenly aware of the cultural connotations that make a color, shape or material high or low class – for example, marble is commonly found in banks and corporate offices, while plastic laminate covers the tables of suburban fast-food restaurants, and a bright, diffused color looks like it could have come straight out of a South Bronx graffiti writer’s spray can. By scrambling those connotations, and combining expensive materials with inexpensive ones, Memphis pieces symbolically laugh off the distinction between socio-economic classes, inventing a new, democratic, stylistic syntax.

Existing in a grey area between art and furniture, a Memphis piece might also prompt questions or invite contemplation, its irrationality jolting us out of our everyday routine. Looking at a sculptural Ashoka lamp or at the alien-looking Cipriani bar can lead us to imagine other countries, other eras or parallel universes in which such unusual objects would have their place. Those daydreams have the potential to counteract apathy and to transform our lives by expanding our conception of society and of our role within it.

In fact, it seems like some Memphis objects (especially the teapots, vases and tableware) were made specifically to inspire their owners to dream up new rituals in which to use them. As Sottsass had learned through his exploration of Asian customs, rituals are an opportunity to pay attention to the present moment, and to remain aware of the passage of time.

Many have accused Memphis of being a novelty, and the group encouraged this view. Memphis aimed to be thoroughly contemporary and forward-looking, its mixture of colors, forms, and materials perhaps mirroring the overwhelming and absurd overabundance of Western society at the end of the twentieth century. The group knew from the start that its designs would soon go out of style, but instead of fearing obsolescence, they saw its inevitability as an opportunity to constantly come up with new ideas. To them, being seen as a fad was a sign of vitality.

As Richard Horn wrote in 1986, “to sit on a Memphis chair is to sit on a question mark,” each piece providing not only a solution to a practical problem, but also an opportunity to examine the ways in which we interact with the people and objects that surround us. For example, with its hard surfaces and strange angles, the Beach lounge chair might be perceived as an invitation to come up with a new way to recline on a lounge chair. Meanwhile, oddly-shaped storage pieces like the Carlton bookcase may prompt us to ask ourselves why we should order and display our possessions in the way dictated by mass-produced furniture. If civilization compels us to act out a comedy in our everyday interactions, how can we control this comedy, or at least try to learn something new about it?

Paradoxically, some Memphis pieces seem so concerned with communicating sensory and socio-cultural meaning that they may not provide a comfortable setting in which to communicate with one another. For example, the Agra marble sofa is visually striking but looks decidedly uncomfortable—it might makes us reconsider the idea of relaxing at home without actually letting us relax. Despite their visual and intellectual appeal, some Memphis pieces have been criticized for their impracticality by those who believe that good design should facilitate human interactions, not complicate them.

Although Memphis objects could be interpreted as pure decoration, status symbols, talismans, conversation pieces and/or works of art, every item also serves a basic practical function: a bookcase holds books, a cabinet holds objects, lamps provide light, and chairs and sofas can be sat on. For the Memphis designers, an object has value because we can touch it and use it in our daily lives. Its function might be manifold and not immediately legible, but it is necessary for a true connection to form between an inanimate object and life.

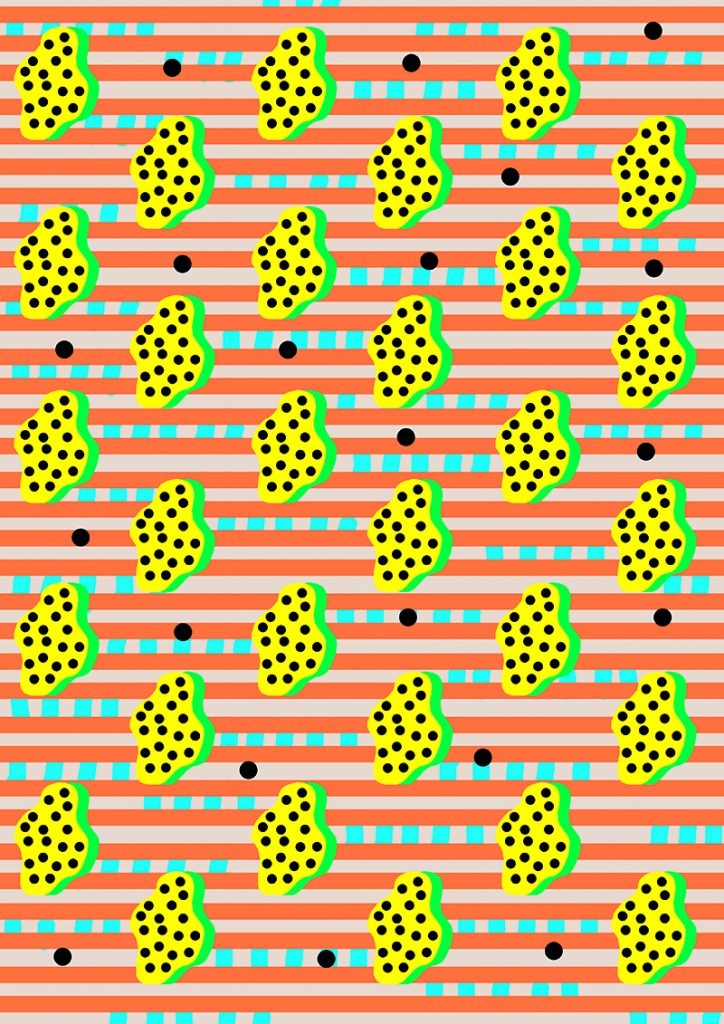

After Memphis’ initial success in 1981, the ever-changing collective released a new collection each year until 1987, moving toward more luxurious materials like silver and blown glass, and introducing a wide range of decorative objects like ashtrays, plates and vases. The group continued to produce new items even after Ettore Sottsass left the group in1985. Several international manufacturers (including Fiorucci, Esprit and Alessi) also commissioned designers associated with the group to create special collections of lamps, teapots, carpets or jewelry in the distinctive Memphis style. Nathalie Du Pasquier’s eye-catching patterns were especially important in the widespread diffusion of the Memphis look because they could be printed on various materials and turned into small items (clothing, dishcloths, pencil cases, plastic laminate sheets, etc.) that were more affordable than furniture, and within reach of a broader market.

The trickle-down effect was all-encompassing, with Memphis-inspired designs infiltrating every sphere of culture. As early as 1982, Crafts magazine proclaimed: “You don’t have to own, or even to have seen a Memphis design for it to affect you sooner or later.” In America, Europe and Japan, countless decorative objects showed an obvious Memphis influence. Meanwhile, Memphis’ official high-quality, handmade pieces were too expensive for most customers, and quickly became status symbols. Memphis designs straddled the line between precious, exclusive objects and mass commodities.

Memphis’ deconstructed aesthetic was initially a challenge to the modernist program, but it was eventually seen by many as a mere style statement, a way for the nouveau riche to simultaneously broadcast their sophisticated taste and their lack of pretension. This interpretation is evident in the 1986 black comedy film, Ruthless People, in which the home of millionaires Sam and Barbara Stone (played by Danny DeVito and Bette Midler) is entirely furnished in the Memphis style, with almost exact replicas of the Bel Air chair, Lido sofa, and Plaza dressing table. The Stones’ over-the-top décor is clearly meant to convey their shallowness and their preoccupation with displaying their wealth and keeping up appearances.

In the late 1980s and early ‘90s, the Memphis style became entrenched in youth culture, its bright colors and cartoonish shapes strongly influencing the aesthetic of toys, board games, and television shows like Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, Saved by the Bell, and the French-Canadian series Robin et Stella for years after the Memphis group itself had dismantled.

It’s been just over thirty years since the Memphis group came together, but many already regard its designs as contemporary classics. In the last decade, dozens of designers and artists (many of them born in the 1980s and early ‘90s) have been using a variety of strategies to bring the Memphis attitude, history and instantly recognizable style into today’s reality.

The 24-year-old Brooklyn-based furniture designer Misha Kahn shares Memphis’ interest in devising complex systems of sensory and cultural signs rather than “simple, smart solutions.” In his More Like You buffet, a pink neon tabletop balances on a wedge whose surface is inspired by one of Ettore Sottsass’ lesser-known patterns for Memphis. Sottsass’ patterns drew attention to the flatness of surfaces by giving them an artificial texture and dimensionality; Kahn did the opposite, gouging the pattern into ebonized wood in order to make the natural material look more like one of Memphis’ signature plastic laminates.

Today’s designers sometimes use new technologies to pay tribute to the pioneering designers and their work. For example, Belgian illustrator Tim Colmant recently created a series of patterns that commemorate Nathalie Du Pasquier’s hand-drawn designs, but were made with MS Paint. With names like Safari and Afrika, Colmant’s patterns are printed onto shirts and hats on-demand by the online design/retail platform Print All Over Me. For a total look, Coltman’s hat and shirt could be worn with Adidas’s 2005 limited-edition Sottsass-inspired sneakers, American Apparel’s multicolored Memphis socks, and a jacket and purse from Proenza Schouler’s/ Fall/Winter 2013 ready-to-wear collection.

Recent Memphis-inspired creations are even more aware of themselves than the original pieces were because, in addition to their striking appearance, these post-Memphis designs often comment on the original movement, its star designers and its many by-products. For instance, the Bacterio bookends by Portland’s Table of Contents Studio are made of wood covered with plastic laminate in the Bacterio pattern designed by Sottsass in 1978 (and used in many Memphis pieces). Table of Contents appropriates the well-known pattern to comment on its impact on design history: “We're fascinated by the process of dispersion: how an idea or symbol that begins in one place or among one small group finds its way into the minds of millions . . .What began as an expression of anti-design, of the miscegenation of high and low culture, now, 35 years later, stands as an iconic signifier of ‘important’ design.”

The 29-year-old Philadelphia designer Brendan Timmins has an equally conceptual approach, but one that brings into play his ’80s childhood memories. Timmins says that his discovery of the Memphis group's work in a design history class was a revelation: “Prior to that point, I had tried to reference the ‘Pee Wee’ style without knowing its name or the proper historical context. After I learned about it, a lot of self-prescribed limitations about ‘good design’ were lifted from my work, and I felt better about making work that might not be appealing to everyone.” Since then, Timmins has referenced Memphis’ “seemingly disjointed combination of shapes and materials” in many of his pieces, most recently by combining scraps of plywood, marble, and metal rods in his geometric Threshold bookends. He also uses parts from Zolo “playsculpture” toy sets to make lamps that highlight the group’s enduring influence on the design of everyday objects. “I like the idea of these toys, a distant echo of the Memphis group’s design experiments, being repurposed as a new design object.”

This is why the post-Memphis aesthetic has such a broad reach now, infiltrating every realm of design at once. It appeals not only to designers and consumers who know about the work of the Memphis group (and perhaps about the radical ideas behind it), but also to those who simply feel a connection with objects that evoke and reinterpret the Memphis-lite style of the ’80s and early ’90s. Memphis references in current design seem unanimously positive, embracing the original aesthetic earnestly, without irony. Maybe that’s because today’s young designers admire the Memphis group’s game-changing ideas about design, but also grew up in a period in which the once avant-garde style permeated mainstream youth culture. They now approach the Memphis aesthetic with a mixture of childlike wonder, reverence and, in many cases, nostalgia.