Chillzone by HANDJOB Gallery

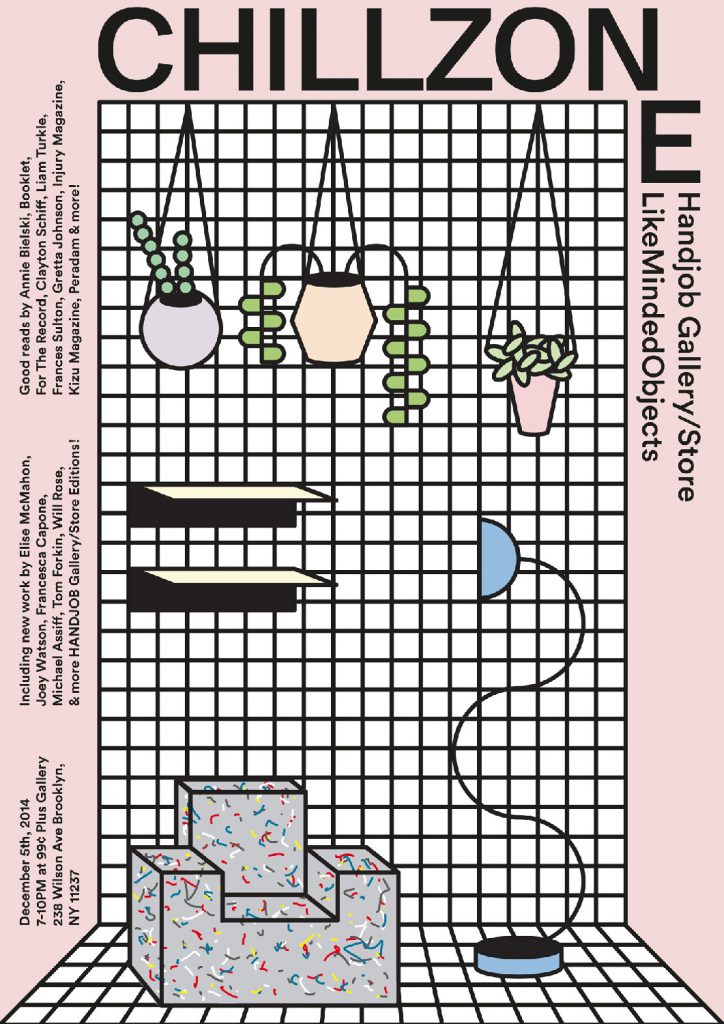

CHILLZONE was an experimental living room installation co-curated by Zoe Alexander Fisher and Elise McMahon, which took place December 5th, 2014 to January 25th, 2015 at 99¢ Plus Gallery.

Zoe, founder and curator of HANDJOB Gallery/Store and co-curator of 99¢ Plus Gallery, works toward dissolving traditional contexts for viewing and consuming art and design by creating alternative contexts and spaces for objects, such as HJGS. HJGS is a storefront and online commercial space that sells exclusive limited editions of handmade and “functional” objects handmade by contemporary artists. Elise is the creator of LikeMindedObjects, a Furniture/Sculpture concept brand which is also used as a platform to create situations exhibiting other artists’ (often semi-functional) work.

Among other collaborations, Elise is also a co-creator of Petrella’s Imports, an ongoing project which began by distributing art content via the newsstand at Canal and Bowery, and continues to explore art consumption and distribution through self-generated digital and physical outposts.

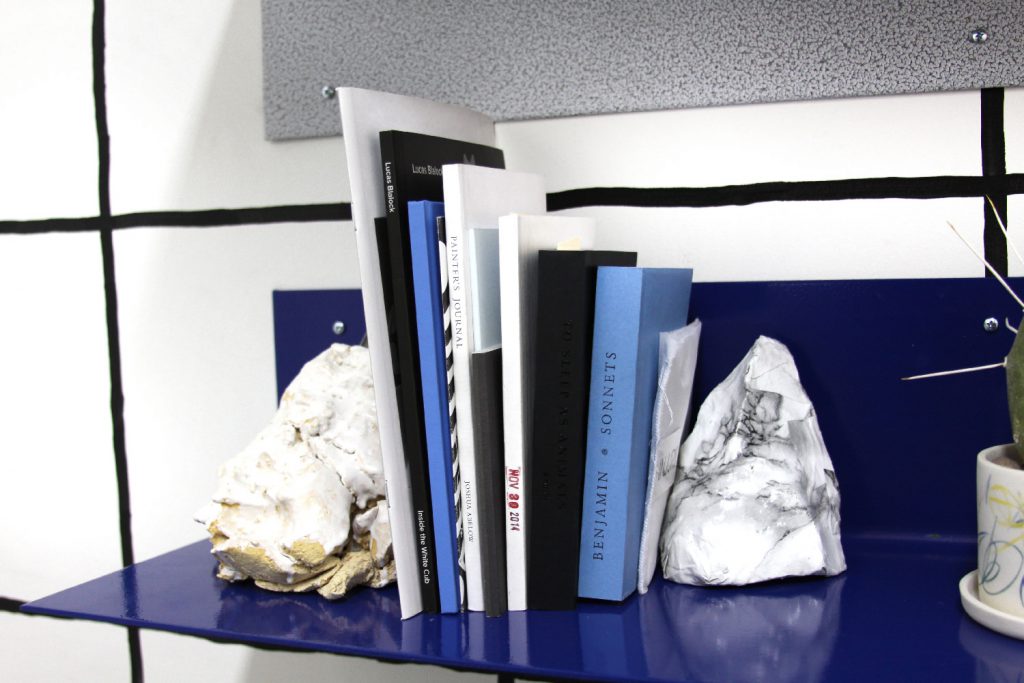

Upon meeting, Zoe and Elise quickly jumped into working together, realizing that their interests, goals, and beliefs surrounding art and design had much in common. The CHILLZONE installation was an opportunity for them to together explore the concepts of art, space, and interaction, creating a space which included the work of over 30 artists via books, furniture, sculpture, lighting, paintings, and more. The project’s success depended on not only the installation, but also the interactions that would exist within it. Thus began the CHILLZONE SESSION. The CHILLZONE SESSION consisted of an assembly of a diverse group of artist, designer, and organizer peers who Zoe and Elise personally note as having a unique take on approaching art and design.

The following is an excerpt of conversation from the CHILLZONE SESSION; including the voices and perspectives of Mike Assiff (MA), Anne Libby (AL), Chen Chen (CC), Jon Wang (JW), Yaron Pardo (YP), Misha Kahn (MK), Tommy Coleman (TC), Liam Turkle (LT), Nick Demarco (ND), Annie Bielski (AB), Zoe Fisher (ZF), and Elise McMahon (EM).

YP: I’m curious if artists making decorative objects see themselves as designers in those moments of making–if they take on different responsibilities and operate under that understanding, if the artist as designer perceives his or her own role differently or separate from “the real artist me.”

ZF: That’s something I am very interested in exploring with HANDJOB Gallery/Store. Maintaining this “artists’ autonomy” and confidence in work that is divorced from one’s typical artist practice is tricky and for me, it is about both the physical and conceptual context of the work’s presentation. How does one maintain that “artist” value across all practices, explorations, and collaborations? For me, by creating a physical space that immediately acknowledges that art and design/consumer objects coexist, the relationship/value is explicit. I ask artists who may or may not have ever made a “functional” consumer object to make something other than their “regular” art practice.

YP: Do you find that to be devaluing?

ZF: I think some people do.

YP: Well, do you?

ZF: No way! I think bringing art into everyday life is the most important thing you can do. I’d like to believe that HJGS creates both a conceptual and physical framework for these art/design objects that allows them to maintain a certain “autonomy” and value.

EM: Do the roles of artist or designer have any distinction for you and your work, Nick? Like, does making something functional or non-functional provide differing constraints or value systems?

ND: I definitely think about and approach art and design differently; to me there's a few key distinctions between the two. One separation are the internal or external constraints. Art is all about the internal world of the artist, and the only limitations are-self imposed (what the artist does or doesn't want to do) or what the artist is physically capable of. Design is about external constraints, from dry things like clients, marketplaces, and production, to more thoughtful things like how a chair feels on another person's heiney or what room to put it in. Art may deal with ideas and structures and whatever else in the larger world, but it is innately selfish, focused on whatever the artist wants to focus on. While design can be heavily authored, it is still intrinsically intended for use by another person, to functionally exist without any knowledge of why the designer made it. Another key difference is use and uselessness. What makes art so great is that it is completely useless, serving no purpose other than to exist, to communicate itself. Design, no matter how weird or unique, still has a use. A knife is not really a knife unless it can cut.

MK: I sometimes oscillate between wanting to be a designer or artist, and caring whether people consider me one or the other, but always try to fall back on that I don't value one higher than the other or bother to differentiate between the two when considering something I'm looking at.

LT: Art objects seem to have durability lasting beyond fashion or the momentary. It is very different to act as a designer for a client with a monetary exchange than the way that an artist would want to make self-motivated work or create personal functional spaces and life accessories.

ZF: Chen, out of everyone here I would say you play the “designer” role most clearly with your sort of more “mass-produced” products like the cement planters, but you also experiment and make small limited editions like the Utility Knife edition for HJGS. Do you place a different value on these objects and projects?

CC: I don't think there is a real difference in the artistic value of any of our output. To us, design is about problem solving. Our mass-produced products have many more problems to be solved, so they are restricted in what they can be. Our limited edition pieces or one offs have fewer things restricting them, so they can be a more free expression of what we find interesting. With the cast cement fruit planters, which we are producing 6000 or more of, for every batch we approach it as a tweaking of the production method, refining the mix or mold, continuously making adjustments to our methods to improve the quality of product.

ZF: So a sort of industrial production system to meet a “design standard?”

YP: But you wouldn’t consider that selling out?

CC: Like I said, I think design is about problem solving, and that was solving a problem; I needed to think of a product that could be scalable.

MK: I think we have this notion that art is more valuable and design is more commercial, when in most ways it's exactly the opposite. I don't think anything interesting comes from considering the boundaries, but I do think ignoring them is fine.

LT: I remember Elise, you had a teacher who said something like “Every time you make something for yourself, that is a revolutionary act.” Remembering those good-hearted things is nice when questioning the role and purpose of the artist or designer.

EM: Yes, that was John Dunnigan. He is poet and furniture designer. This thinking helped me feel comfortable taking on these roles, the idea that simply providing for yourself is one way to combat an acceptance of monoculture. I also think that the term “selling out” is not actually applicable anymore. We are no longer in the ‘90s where everyone has piles of money and can be above self-promotion or working within “the system.” Independence is the real goal, even if working within the system helps achieve that.

MA: There is a line that is crossed when I make a functional thing, to enter that designer role. I am kinda creeped out by it. I am just so worried about consumerism in general; a lot of my art is on the other side of the fence, “I think this society is somewhat fuckkkeddd…” you know, trash economies, environmental collapse, so on... so whenever I make something that is too easily devoured, people wanting more of something, that creeps me out. I also am uncomfortable with "do good" design that says “Smart design will save us.”

AB: It’s funny that you are uncomfortable making a design object, since your objects included here started out as functional and then were altered, actually making them less functional, like the electrical cord vessels that wouldn’t actually hold water or the toilet paper that has been dyed…

YP: It’s interesting that you’re creating these non-functional, almost waste objects. You and I have talked about this before–this idea of necessary sacrifice as a concept specific to art–sacrifice of material as well as comfort in order to generate an alternative or to counter an object that has been refined, perfected, cleansed. Like here, the amount of destruction and waste that happens in order to make a symbolic gesture with that dyed toilet paper roll is a fraction of the waste that is made in the production of millions of usable rolls, just so that we can take a shit in the way we do. It’s just not the way that civilization has shat forever–this is a pretty new thing. In many ways, this is where I actually find that artists can have a really important voice in problematizing objects and the constructed world–but who really knows where problematizing things get you?

EM: Maybe that’s a difference between the roles of a traditional artist and designer; whereas maybe a designer would be more interested in convincing someone to purchase a product as a solution, an artist is hopefully inviting you to consider alternative ideas of your own by proposing an alternative of their own. Like, the difference between “This is my solution” or “What is your solution?” But of course, this is not every artist’s agenda.

TC: Well it speaks to the void for an artist to be poetic or a designer to be more concrete.

LT: It’s the difference between designing away a problem in our society, like access to clean water, instead of ideologically getting everyone up to speed so that anyone could potentially provide for themselves.

YP: Well, you’re moving into different aesthetic realms when the scale changes. Designing water system infrastructure, or sustainable recycling, cannot be aestheticized in the same way as a small object that looks like a similar object, but way grosser.

AL: Well these systems are not privileging aesthetics over functionality. It’s not about how it looks–there is an aesthetic to it, but it is not the priority.

EM: But then the difference is, I would happily use up all the toilet paper I bought at the store, but your toilet paper I will put on my shelf at home, look at it, and tote it around with me to any living space I inhabit for the rest of my life…

YP: ...and then if the apocalypse happens you will luckily have some toilet paper around.

EM: Yes, then I will be like, “Thank Gawd for this Art!”

MA: So, what’s trending guys?

AB: Sincerity is trending...

EM: Yes, I am happy about that, but what about that awkward sincerity when someone discusses “craft” or “makers.” I think those words can make people uncomfortable with making functional things.

JW: Yeah, the word “maker” makes me not want to make things.

YP: Well, these words are used as tricks, and in this case “makers” is being used in a very branded “Brooklyn revival” sort of way. I am not comfortable with being called anything that could help a government official get elected.

CC: Yes but also, those words just mean handmade—having gone to school for industrial design, crafting was not something that we were that interested in, but starting out, you don’t have the ability to hire a factory to produce your things, you have to make everything yourself. I guess that is “craft.”

ZF: But if the term "craft” implies a traditional system of making, and you are inventing your own production systems, you are taking yourself out of the the “craft” category.

TC: To be a maker has an assumed independence, the power to make my own world/things–that’s why I’m interested in if people actually use and live with their handmade things. Like, do you use your own knives or shanks Chen?

CC: Well that project started because we needed some sharp things made for studio. We made a machete because we had a backyard where you could get to the water if you hacked your way through the trees.

YP: Weren’t you tempted to just order it off amazon?

CC: No, we were having a BBQ and wanted to get to the water right then, so I just welded a couple pieces of steel together and sharpened it…

AB: Even, still. You could have just used Amazon prime.

EM: Moving away from traditional crafts into a newly-invented manufacturing system is something a lot of people are exploring right now. Like Misha with his sewn vinyl cement molds, or me with the powder-coated tinfoil. Combining the desire for efficiency while maintaining that each object is unique–the artist factory, or something–it comes at a time when more and more new contexts are surfacing for viewing and experiencing art. I appreciate that these artist-generated project spaces inherently can not be as sterile a context as a traditional gallery because the human presence and interaction is encouraged and necessary within the content–like some of our own projects, HandJob, Petrella’s, UpfrontNight, LMO. Jon, with ZeZe Hotel, you are playing with these things by allowing people to rent the exhibition space as an Airbnb apartment. Could you talk more about that context?

JW: I wanted to create a “comfortable” exhibition space where you could spend the weekend with a painting or a couch, take a nap with a sculpture, or kiss a countertop. Everything at Zeze from the bathroom tiles to the cat toys are conceived and created by artists and everything is for sale. "Zeze" is an informal japanese term for the state between sleep and wakefulness. It's about anesthetizing the lines between art and furniture, domestic space, and retail space…napping and shopping...

TC: The balance of art space to interior design experiment is interesting in this context, and how it is understood may come down to the documentation. If someone comes in and documents it as an arts space, the authorship is in the arts space–and the opposite as an interior design magazine spread. It’s funny that it can go in all directions and it is your role as manager/curator of the space to influence how it is digested.

EM: I find it exciting that within the role of the orchestrator or curator, you get to manipulate the entire relationship of producer to consumer, object to user.

ZF: Me too! Within that curator role, I’d like to think one can provide a context and also therefore project a certain value system on the works. In the case of CHILLZONE we decided on a faux living space to be that context. Therefore, all the works were intended to be “lived with,” touched, and used. The value of the works in the space became not only aesthetic and conceptual as with a typical gallery setting, but also semi-functional… or faux-functional...

MA: Maybe it’s unhealthy but I would be most comfortable with my art just being in a white box… I have drank the Kool-Aid so hard.

EM: Well isn’t that the ideal—someone just loves your piece so much that they buy it and install it in a white box wing of their home.

MA: Yes and within that white box the viewer didn’t even touch the floor, they hovered over the floor… I know, it’s insane, it’s not healthy.

EM: So how do you go in another direction, where you feel comfortable with the people who can afford to purchase your work, putting your work in a setting you don’t have control over?

ZF: Or a curator putting your work in a setting like the CHILLZONE–among so many other works?

LT: Or what if they are trying to match it with their green couch?

AL: Historically a white space is only a relatively recent context for art. I mean, it would be interesting to try to innovate more of a vacuumed space. The White Wall–I don’t see it as a context without meaning, it’s just what we absorb to be standard at this moment.

MA: A piece of art emerging from an ether or a piece of art in heaven, a white homescreen heaven...

AB: There is no pure sensory deprivation tank for an isolated viewing experience–and even if there were, you’d have to talk to and pay the guy when you walk in the door. I think about how much art viewing happens on my phone, on Contemporary Art Daily or Instagram, another white box. With Instagram for instance, if I’m looking at a painting, I’m looking at it through the context of who has posted it, and among a slew of vacation pics, selfies, breakfasts, dogs, memes, etc. Everyone posts for a reason: to promote themselves or a friend, to say “I am here at this show!”, to align themselves with the work/idea/aesthetic, to express excitement. If John Berger were here, he’d be blogging “Ways of Scrolling.”

MK: I think many of us prefer our work to be found in that rare unsuspecting moment, half delirious and stumbled upon, no? Seeing something in a gallery or museum can ruin everything with expectations, baggage, and uninteresting comparisons.

Z- Personally, this is actually one of the most exciting things about art–the post-production and post-consumption life of the art object, where it ends up and how it is used/displayed. My ideal would be a space that is full and lived in with a closeness to the object–tons of artists, tons of objects, some touched and lived in, others remaining precious (on a white wall or pedestal)

MA: My paradigm would be to potentially exist with only one piece of art in your house, everything is white, and there is that one piece on the wall.

YP: Well, you don’t have control over that.

TC: So wait, what happens when that one work doesn’t strike you the way it used to? Do you break up with it?

MA: Oh like, you chose the wrong marriage? That would be like having a kid and putting it up for adoption in its teen years…

AB: Or you just put that kid in storage...

YP: That also comes from a very different value system. I think especially for younger collectors, value is not so speculative, it’s much more an appreciation for the actual thing. Which seems a little more accessible with design actually. Like, “oh I got this thing, I like it, it relates to me and my life, I have curated it into the way I move about.” Whereas an art collector will likely put it in storage and then maybe put it up for auction in a few years.

EM: I suppose that is why I value these functional objects: including something into your life to an extent that it wears down with use, and couldn’t be sold at auction; defining your personal space and lifestyle; influencing daily activities to become as potent as performance.

ND: What I always like to say is that the chair might not be art... but sitting in it is!