East Village Eye

by Claudia Eve Beauchesne

Leonard Abrams grew up in a small town in upstate New York. He couldn't stand the small-mindedness of the people there; couldn't wait to move to New York City, where there was art all over the streets and "people didn't care," which was OK with him. After going to college and spending some time in Denver and in Boston, he finally moved to New York for good in the mid-seventies and started working as a bicycle messenger.

At first, Leonard lived up on West 63rd Street, but soon, he moved to the East Village, where a one-bedroom apartment cost as little as $120 a month. New York City was near bankruptcy at the time, and almost everything was in ruins below 14th Street, with many landlords abandoning their buildings or hiring professional arsonists to burn them down in order to collect insurance money. "There wasn’t a night when a building wasn’t going up in flames," Leonard remembers, "particularly east of Avenue A, which was the red line. But a lot of people didn’t know that it wasn’t as dangerous as it looked.” Yes, the East Village's streets were full of homeless people, junkies and drug dealers, but there were also a lot of Polish, Ukrainian and Puerto Rican families, and a growing population of young artists and misfits who, like him, had escaped their stifling hometowns to look for freedom and for each other.

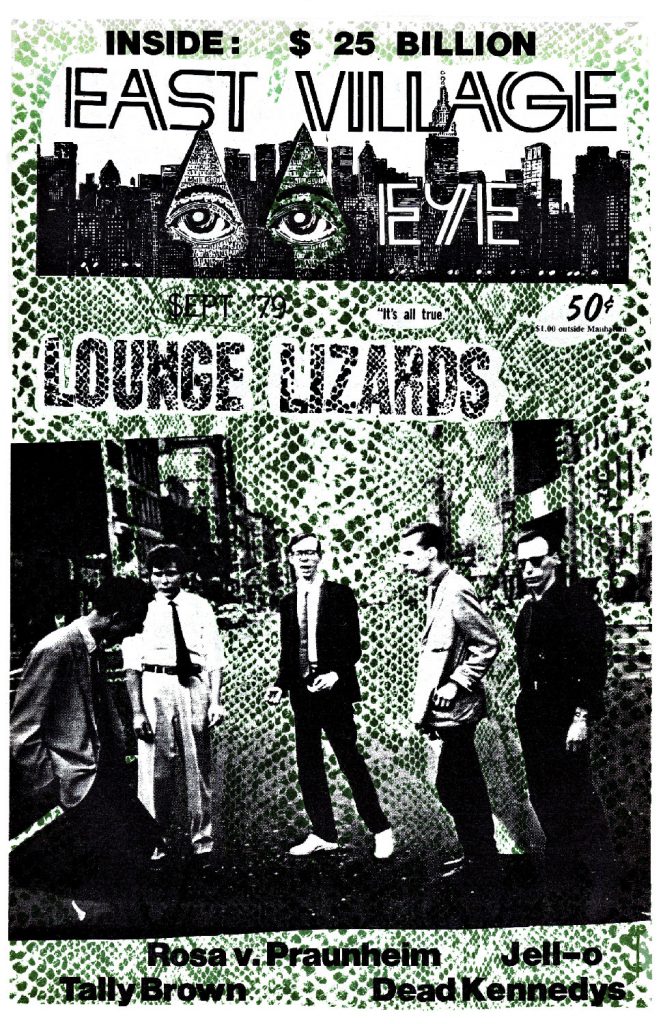

"Even the artists weren't making art at the time, says Leonard. "They were making music. People were turning away from anything that could be commodified, making stuff that could never be sold, starting art bands, conceptual bands, avant-pop, whatever." Everything happened between midnight and five A.M. at clubs like CBGB, A's, Tier 3 and the Mudd Club. That was where music, art, fashion, cinema and theater converged, generating raw, hybrid performances that reflected the city's chaos.

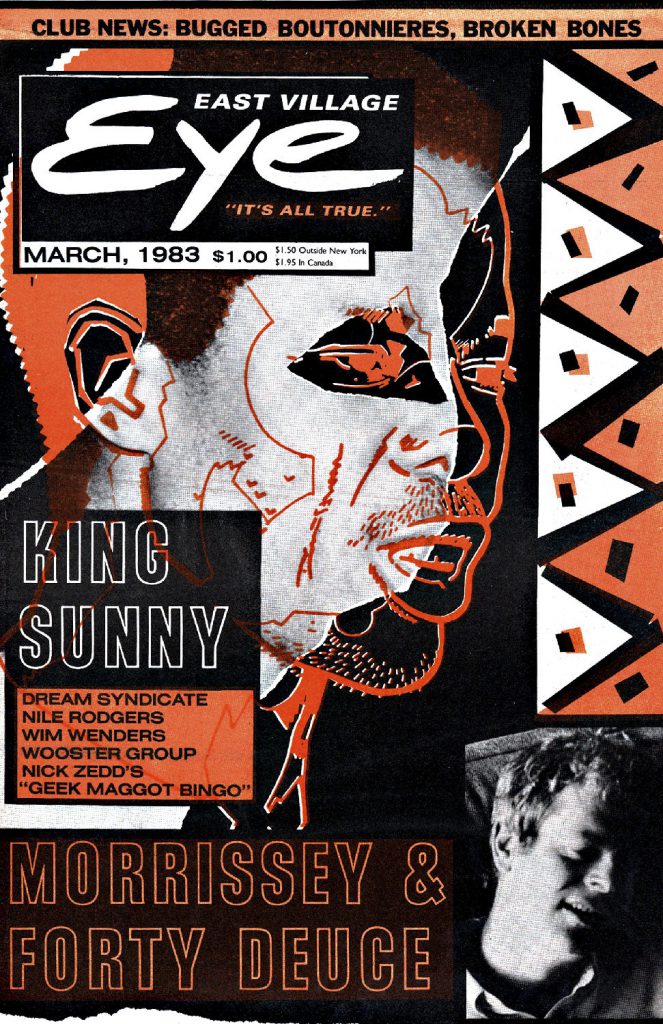

Leonard had always wanted to start a newspaper. He had started one in high school, and then another one when he lived in Denver but it had been a flop. In early 1979, at the age of twenty-four, he finally did it. He rented a basement on Ludlow Street, got some friends together, and started working on the first issue of a monthly paper that he hoped would reflect his neighborhood's gritty grandeur, The East Village Eye.

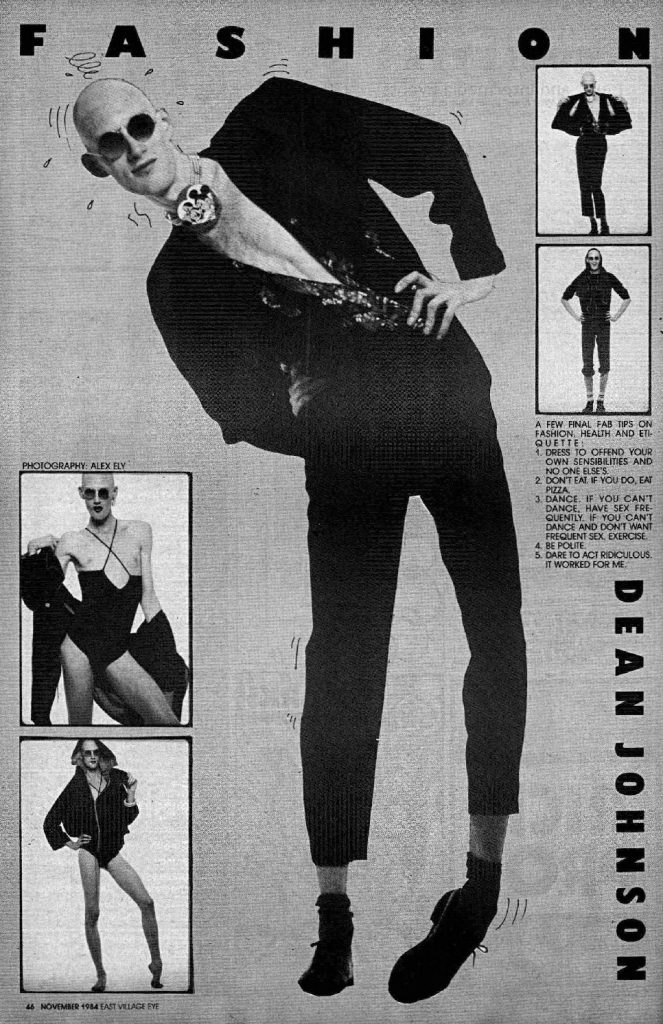

"I wanted to create a community in print; that was my idea," Leonard recalls. To him, culture was more about participation than about consumption, so anything that was happening in the East Village or the surrounding areas was fit to print. Serious issues and hearsay were given equal play – “It’s All True” was the Eye's watchword. The paper incorporated local news, art, film, theater and music coverage, literary fiction, comics, fashion spreads, a centerfold featuring the work of local artists, and plenty of gossip about downtown stars like style icon Anya Phillips and time-experimenting artist David McDermott. And the design was as expressive as the content—instead of following a consistent layout, art director Christof Kohlhofer combined photographs, illustrations, text and splashes of bright colors in different ways each month. Even the logo kept changing. The Eye strove to be "a wellspring of information and a source of inspiration" that told the neighborhood's overlapping stories "insightfully, intriguingly, and incessantly."

The winter of 1979 was a short one. By early March, spring was in the air and everyone who was anyone was going out every night. Club impresario Rudolf remembers coming across the first issue of the East Village Eye that May. "All the trendies on the second floor of the Mudd Club were talking about it! Everything was so unpredictable, including the fact that you never knew when it would come out. A total surprise! One used to buy it at a newsstand on 2nd and St. Marks after a royal dinner at the Old Kiev, when the first lights of the morning were approaching and all the bums were stiff-cold-asleep. Then, one would go home, preferably with somebody, and lay the paper aside to read it for breakfast at five in the afternoon."

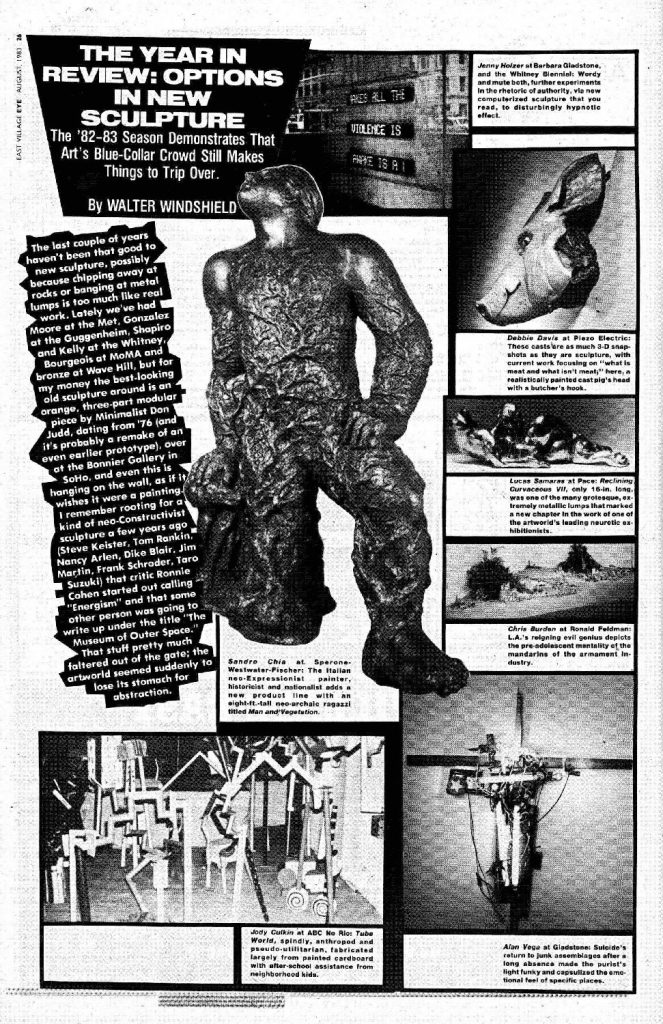

At first, the Eye was mostly about music and performance (it was the first publication to mention the term "hip hop" in print), but the visual arts section eventually grew, reflecting a shift towards painting, sculpture, and installation as the economy improved. After documenting seminal group exhibitions like The Real Estate Show in 1979 and The Times Square Show in 1980, the Eye began to chronicle the proliferation of small, artist-run galleries in the East Village, starting with the Fun gallery in July 1981, followed by 51X, Gracie Mansion, Civilian Warfare, Nature Morte, Piezo Electric, New Math and the dozens of others that opened and closed constantly over the next five years. At its peak, the paper sold 10,000 copies per month, not only in New York but also to subscribers all over the world.

In the summer of 1983, Walter Robinson, a painter, writer and former publisher of the influential magazine Art-Rite, became the Eye's art editor, enlisting the 22-year-old college dropout-turned-critic Carlo McCormick to help him cover the art beat. As Leonard remembers it, these key contributors came on board by chance: "We had this art editor, Eric Darton, who was leaving so I said to Walter at a party, 'I don't know what I'm going to do for an art editor.' And he said, 'I'll do it.' I said, 'Do it! Great!' I knew that he was a heavy hitter... Then Carlo popped up, this neo-hippie with a carrot red, bowl-shaped haircut and love beads." The two would go on to have a huge influence on the Eye's tone and content.

Walter shared Leonard's democratic approach to journalism: "I wanted the art section to reflect the social reality of the Village–including bad art by losers, which is edited out of the regular art magazines. They falsify history. WE were the honest ones!" He often wrote under the pseudonym Walter Windshield (a reference to the legendary gossip commentator Walter Winchell) and liked to subvert the conventions of traditional art criticism. One time, he reviewed an exhibition that he hadn't even seen: "I just went by and looked in the window during the opening. It was real crowded so I wrote a review from what people had said." Another time, in an incident that became known as "Waltergate," he wrote a column using material borrowed from a press release without crediting the gallery, and attributed a quote by the famous surrealist artist André Breton to a local art critic. "It was very post-modern," he thought. "You just construct this text that purports to represent an art scene from the signs that are circulating." In response to complaints, Leonard printed an apology, stating that Walter had been suspended without pay, which was a joke, of course, since nobody at the Eye got paid.

Carlo brought the same irreverent attitude to his Art Seen column, exhibition write-ups, and the gossipy quizzes that he put together for the Eye. "I would write lies about people, you know, misinformation; I loved that. I'd talk about somebody's drinking problem more than about their art or something... just pressing buttons, seeing how people would respond." He also made a point of interviewing the non-white, female, and/or queer artists who had found a home in the East Village and who made unclassifiable things like wall shelves encrusted with fake pearls (Arch Connelly) or life-size transgender dolls (Greer Lankton). His writing mirrored the ironic, pseudo-anti-establishment stance that set the East Village scene apart from the "real" (i.e. elitist, profit-driven, humorless) art world embodied by glamorous Soho dealers like Mary Boone and her all-male stable of white, middle-class painters.

Walter, Carlo, and the Eye's other art writers (including Jane Webb, Nina Garfinkel, Yasmin Ramirez-Harwood and Sylvia Falcon) brought the East Village scene to life for readers, creating a neo-bohemian aura around it by reviewing not only the artwork but also the scenesters' outfits and hairdos, the inter-gallery romances and rivalries, and the drinks served at openings (one gallery had "refreshing gin and orange," another "a vodka punch jam-packed with healthful fruit.") They were "snickering and giggling through the art scene" but also essentially creating the scene by seeing every show in the neighborhood and writing about it all as if the East Village was the center of the universe because, to them, it was. "We didn't care about the rest of the world," Carlo remembers. "If you were famous in our world, you were famous." The Eye's art critics made fun of a lot of people, but they were genuinely devoted to the neighborhood's artists. "I could have been writing for a fanzine," says Carlo, "except that the stakes were higher. I was basically a fan."

For Leonard, the role of the cultural underground was "to create a network of people who help each other to deal with the profit pushing commercial structure... by producing stuff that is alive, that says something, that breaks people out of vacant TV test-pattern consciousness—that brings them back into the human race so that they're more than just walking dollar bills for the benefit of con men." But as mainstream art magazines like Artforum, Flash Art and Art in America began to publish enthusiastic articles about the East Village scene (one of them penned by the Eye's own, Walter Robinson and Carlo McCormick), the neighborhood became known worldwide as a pleasantly risky avant-garde playground where a discerning collector might discover the next art star before everyone else. By 1984, the art market was booming and the East Village's artists, once so opposed to making "stuff that could be sold," were becoming willingly (and irretrievably) entangled in commerce.

In October 1985, in a full-page article entitled "East Village, R.I.P.," Carlo McCormick declared the East Village art scene officially dead, a victim of the media hype that the Eye had helped create. Leonard was reluctant to publish this bold statement, but he ran it anyway because that was what the Eye stood for: voicing opinions, no matter how unpopular. By then, local artists and dealers had been featured in People magazine, Life magazine, and in a 13-page fashion editorial in Italian Vogue. Tour companies were leading busloads of visitors on "urban safaris" through the neighborhood, stopping to pose for pictures in front of rubble-strewn lots and graffitied walls. Carlo thought that the scene had become a parody of itself, a tourist attraction. “We, who were the first to take credit for the birth of East Village art, now want to be the first to take credit for killing it," he wrote. "After two years of intense coverage of the scene, the Eye has officially run out of gimmicks to repackage the same old drivel."

The locals were flabbergasted by this unexpected East Villification. “I don’t know what the heck he was talking about! I didn’t feel dead at all!" exclaimed the artist Rhonda Zwillinger twenty-five years later. "He published that because everybody wanted to be a spectacle. Unless you’re a spectacle, you won’t have an audience so you need to create a spectacle.” Carlo admits that his statement was totally flippant, just like almost everything else that he and Walter wrote for the Eye: "I knew that I was shooting myself in the foot but I was pretty sick of the scene by then... I was tired of the hype... I believed that the scene was over, to some degree, but I didn't mean to thrust a knife into its belly and twist it." Still, many people felt betrayed. One gallery owner didn't speak to him for months after that.

The obituary may have been premature, but Carlo had seen the writing on the wall. By mid-1986, the term "East Village" was being thrown around like a brand name to sell everything from T-shirts to cocktail glasses, blue chip galleries were poaching artists from small East Village galleries, and rents were soaring in the neighborhood, forcing many galleries to close or relocate. The East Village Eye tried to adapt to these changes by becoming somewhat slicker, switching from a tabloid size to a magazine format and introducing a glossy cover. That fall, it also broadened its scope by changing its name to The Eye, and then to The International Eye, but its advertising revenue was plummeting as galleries, clubs and other small businesses were priced out of the neighborhood. In January 1987, the magazine released its last issue, a collage of previously-published articles that read like a who's who of the East Village scene and summed up the paper's eight-and-a-half year run.

Both in form and in content, the East Village Eye mirrored the rise and fall of the East Village art scene of the '80s. A subculture that glorifies irony, nihilism, and a perpetually festive atmosphere is bound to be ephemeral, but Leonard Abrams' newspaper managed to encapsulate more of what was unique about that particular time and place than any other print publication. So what if the Eye was a party paper? The paper was a public party. "To have presented so many idiosyncratic voices in such a deadpan manner, as if what they said was as obvious as the weather... that was fun."

Sources

1. -Leonard Abrams. Letter from the editor. East Village Eye, September/October 1980.

-Leonard Abrams interviewed by Jim Cornwall, 2000.

-"Q-and-A with Leonard Abrams, publisher of the East Village Eye." EV Grieve, Dec 6,2012.

-Liza Kirwin. It’s All True: Imagining New York’s East Village Art Scene of the ‘80s. PhD diss.,University of Maryland at College Park, 1999.

-Carlo McCormick. “East Village, R.I.P.” East Village Eye, October 1985.

-Alan Moore, "50 Big Ones: The Rest is Yet to Come." East Village Eye, Dec 1984/Jan 1985.

-Tiernan Morgan. "The East Village Eye: Where Art, Hip Hop, and Punk Collided." Hyperallergic, November 12, 2014.

-Rudolf Pieper. "Night Journeys Many Years Ago." East Village Eye, May 1984.

-Walter Robinson, "Spiritual America: An Introduction." in Spiritual America: The Catalog,1983-1984. by Sandra Schulman, 2015.

-Rhonda Zwillinger interviewed by Claudia Eve Beauchesne, July 2011.