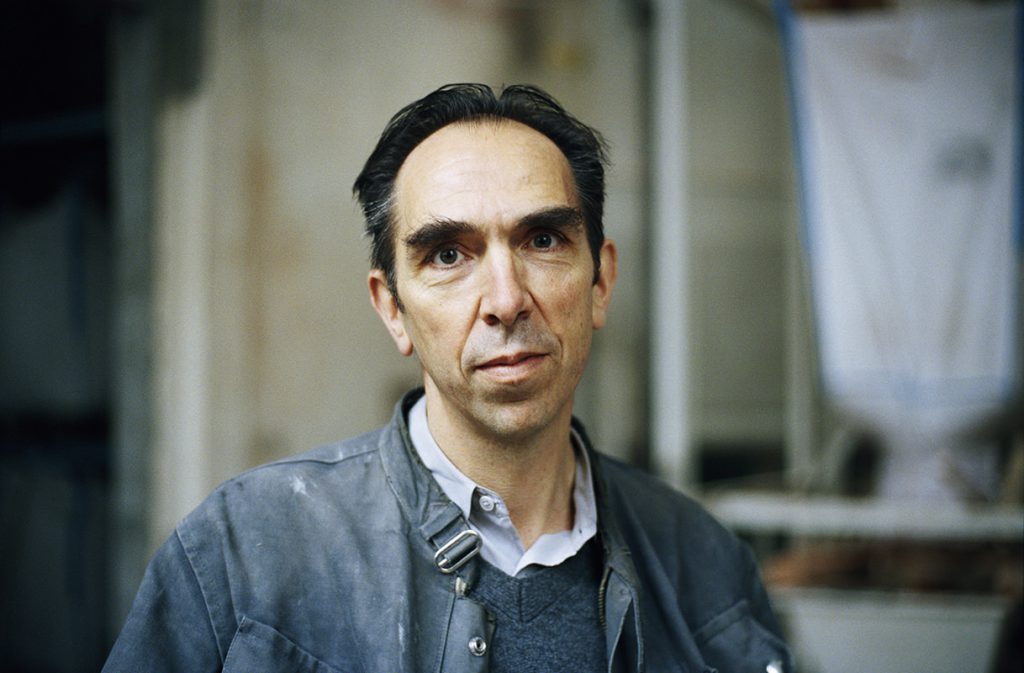

Felix Lehner & Kunstgeisserei

Interview by Melissa J. Frost

Kunstgiesserei is a center for the ancient craft of metal casting, yet it’s anything but antiquated. Dedicated to the making of art, they are as experimental and innovative as the field they serve. They are also equally expansive, working in a global art culture with a full spectrum of materials and methods. At their complex in Switzerland, they have a foundry, digital milling center, photo center, library, archive, gallery, and artist residence. They also have an outpost in a Chinese foundry. While they are clearly as skilled as any Swiss craftsperson, they collaborate with artists because above craft, they understand the priority of concept, poetics, meaning and experimentation.

M. There is clearly a lot of pride and attachment between Die Kunstgiesserei and the large scale works it has produced. How does the relationship between the art object and the person who creates it differ from that between the art object and the person who conceives it? Energetically, emotionally and logistically?

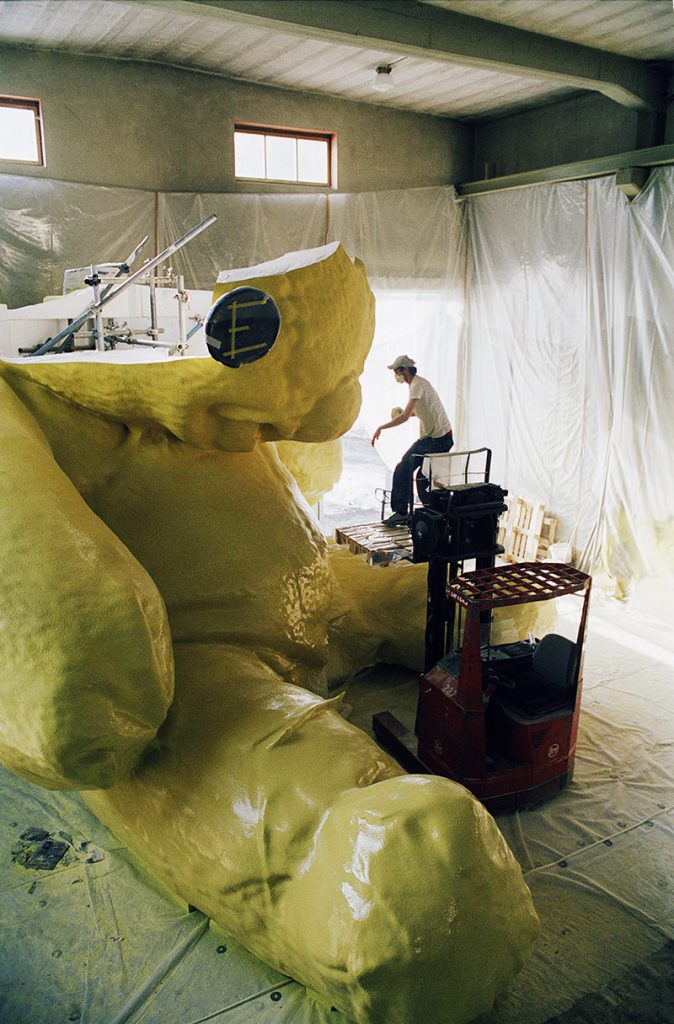

F. We are happy that we were able to realize many challenging and complex works for artists. Large scale, but also small ones. With the large scale pieces, it is a great pleasure to see people from all different backgrounds and with various talents work on one idea, on one thought of an artist, often over years. This can add to the density of a work. At the same time, I don't believe that important works of art solely depend on diligence or will or financial possibilities. For me, the artist is always the author of a work, no matter if he or she executes it by her/himself or if a whole production company is behind it. At the end, it is important that it is in the world and the artist has to stand behind it.

M. In so many other fields and for much of art history, the mastery of a craft was the making of an artist. Where is the line between artist and artisan in contemporary art?

F. In my opinion, mastership should not be reduced to manual skills and technical things. Important and beautiful artworks are often not the ones that are technically the best made. Masterpieces are not necessarily without flaws. In the Renaissance, creation, technical performance and manual work were tied together much more firmly. When I look at technically virtuosic sculptures and casts from Benvenuto Cellini or Lorenzo Ghiberti next to clumsy casts from Donatello that are littered with mistakes, it is still the work of Donatello that moves me more. In contemporary art, there is not a rule for this and every artistic position has to stand for itself.

M. How does Die Kunstgieserei navigate that place between delivering a service and creation? Are craft decisions often independently made in-house or by the artist advised by the foundry? Is there a level of renouncing authorship or no?

F. Each artist has his or her own method. What presents itself for one as ideal production conditions can be distractive and stressful for another. There are no rules—we solely try to set up an ideal climate at the Kunstgiesserei and the Sitterwerk, where the artist can include changes, detailed definitions, specifications during the technical transformation of a work, or have space to include them at a later time.

M. Because you're working with a practice that is six centuries old yet also one of intense innovation and advanced technology, Die Kunstgiesserei feels like a special place of concentrated time, both looking back and forward at the same time.

F. Thank you, I'm happy to hear that. Concentrated time is a beautiful term. By all means, we are not artists but craftspeople, or maybe collaborators, who embrace and sometimes apply artistic approaches within our work. That is sometimes more, sometimes less successful, but always challenging. That's what makes our work so exciting.

M. The non-commercial knowledge-based facilities are beautiful elements to the commercial practice. Were they developed to be an aid to the foundry's craft or as a way for the foundry to share it's knowledge?

F. Both elements are mutually dependent. Die Kunstgiesserei, the Sitterwerk and other workshops attached like the photo lab are conglomerates that should provide the best structure for artistic work and its realization.

It was always important for me to be involved in the creation of art and to be a part of it. For the making of art, technical devices such as an industrial furnace or the most up to date milling machine are just as important as an exceptional material sample, a library or unoccupied space and time in one of our guest studios. The uncommercial Sitterwerk with the library and the material archive, that sees itself also as a research and development center, grew out from this idea.

Through our 30-year-long collaboration with artist Hans Josephsohn, a big exhibition space was built ten years ago. It hosts many plaster originals and casts right next to the foundry. In order to be able to carry the costs for storing, presenting and establishing a catalogue, we received the right to deal with his work directly from the artist. For nine years, we also function as a gallery for Josephsohn. For the international perception and recognition of his work, many artists and curators are frequent guests here, such as Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Udo Kittelmann, Paul McCarthy, Markus Raetz, Hans Ulrich Obrist and many more who have made important contributions. Artists are often the best agents for unnoticed and forgotten positions. Four years ago, a very pleasant collaboration started also with Hauser and Wirth, who helped to increase the radius for the perception of Josephsohn's work.

M. Is the archive intended to be more of a living collection to inform your present processes or more protected for the future as documentation/preservation?

F. The material archive has many different directions and is not solely carried by the Kunstgiesserei. It works within a network of five other material archives in Switzerland. In relation to Kunstgiesserei, the meaning and duties of the material archive have changed over time. From its collection, inspiration and methods of resolutions for totally new work of artists, architects and designers can be found. At the same time, it delivers essential information years after the completion of a work for restorers and art historians.

M. The breadth of fabrication and production is so wide yet so specialized and specific. You're practically in a position to create any art object that can be made. In that, are you at all selective about the larger projects you take? If so what are the qualifiers?

F. After everything, we are a foundry that works with metals and many other materials, mostly going from a liquid to a firm state, taking new forms. In our company, there is a great appetite and interest to solve the most diverse technical problems in relation to art. With some works, we also have to start at zero. The collaboration with an artist often starts with very basic questions such as how to translate an idea into a material.

M. Have you ever turned down a project for philosophical reasons? For stylistic or aesthetic reasons?

F. We were lucky to always have enough work in the last 30 years. For a good collaboration, mutual trust is crucial.

(figure: 5718_04_HR.jpg)