Matthew Connors

CK: What drew you to a revolution

LB: …to which you did not fully belong?

MC: It’s a little difficult to articulate in hindsight. At the time, the events in Egypt felt tectonic. It was a moment in history that seemed impossible beforehand but inevitable afterwards. A torrent of imaginative energy was pouring out of Tahrir and I felt the need to immerse myself in it. I went in not knowing what I was going to see and not sure I would be able to take any pictures that made sense for me.

CK: The way you photograph the people in Fire in Cairo is very similar to your other series, General Assembly. Why did you choose the same approach?

LB: When and why does Fire in Cairo break away into its own language?

MC: It wasn’t my initial intention to approach them the same way. General Assembly had a momentum of its own and was guided by Occupy’s spirit of radical inclusivity. I made the portraits over the course of a year in the most comprehensive way I was capable of doing. The pictures flowed from relationships I made with protesters, our exchange of ideas and my understanding of the social landscape of the movement.

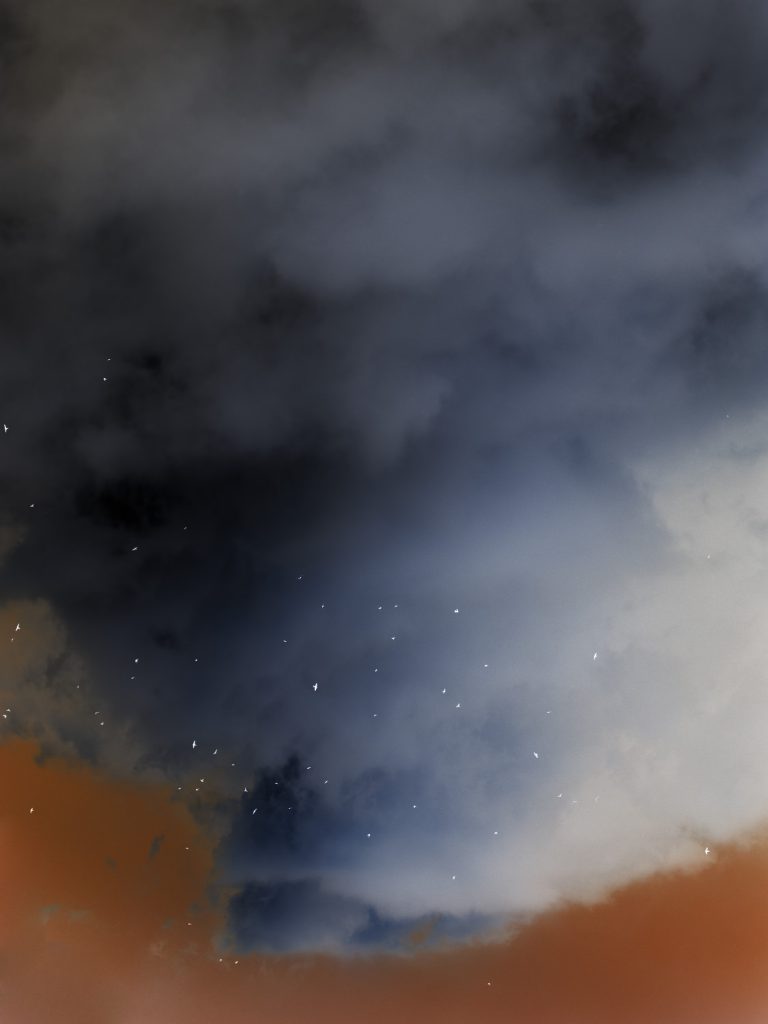

When I arrived in Egypt I knew I could not replicate General Assembly there. The complexity of the situation and my relationship to it resisted that approach. At first, I wandered Cairo with a kind of aimless vision that evolved into metaphorical speculation. The city started to present itself as an enormous studio for social change, rife with visual, sculptural, and atmospheric residues of resistance emerging from the political violence.

As a collection, these pictures felt too removed. I was dealing with only signs and symbols and needed to directly incorporate aspects of lived experience. I began making the portraits as a way of connecting the oblique pictures of struggle to those who were propelling the revolution. On some fundamental level, all the protesters I encountered came to the streets to demand their dignity and recognition as agents of positive change. For most people, the form of the portraits carries those associations. Very rarely did someone in Cairo decline to have their picture taken after I showed them examples of similar ones I had made.

The language of Fire in Cairo rests at the intersection of these ways of photographing and the experimental fiction I wrote. They come together to heighten the tensions between beauty, threat, and historical consequence.

I like how the portraits link this book to General Assembly. Someday I hope to complete a protest trilogy that includes the two, but can’t say yet what the third volume will be or what language it will use.

CK: It was in 2013 that you shot the images for this project, and it took over a year to do the final selection. What are your main difficulties and consideration in selecting the images?

LB: Are your processes for constructing narratives usually this time-intensive?

MC: Yes, I am slow. People close to me will tell you I spend an unhealthy amount of time editing and reworking material. I lack a certain amount of innate talent for it, so I labor over edits, sequences and, in some cases, individual pictures. It stems from my belief that photography is a practice as close to writing as any of the other visual arts and demands a similarly rigorous editing process. With the images and writing in Fire in Cairo, the main difficulty was exercising restraint. There were many elements I considered to be strong that had to be excluded in order for the book to work.

CK: The object configurations or Cairo readymades: you have called them "residues of resistance and forms that emerged from political violence." For me, these are some of the strongest images in the series. And the way you have described them is so poetic,

LB:…as are the images themselves. What led you to aestheticise the conflict rather than simply portray it photojournalistically?

MC: The simple answer is that I’m not a photojournalist. It’s field of photography I don’t have the training or experience to work in. Before I arrived in Cairo, the events had been well-documented by both professionals and citizen journalists. I did not see what I could contribute by working within those conventions. They would not have been a comfortable fit for me.

What photojournalists do is imperative to the health of societies at large, but that does not alter my view of the slippery relationship between photography and the real. I was more interested in seeing what other images could arise out of contemplation and proximity to that moment in Egypt’s history. My goal was to navigate between reportage, poetry and surrealism to find different visual idioms that could express the emotional urgency of Egypt's aspirations.

CK: Most of the images in the series are in portrait (as opposed to landscape) format. Why so?

LB: Though this seems like a photographer to photographer question, as a writer I wonder if photographers attach any symbolic significance to portrait or landscape or whether it’s just a preference in terms of composition.

MC: Most of the pictures I took in Cairo were vertical. It was a way of seeing I fell into that offered some measure of distinction from pictures one might expect to see from that experience. In some rudimentary way the idea of making a book was also in the back of my mind while I was shooting, and the book I envisioned had a vertical format.

CK: Why the diptychs?

LB: There doesn’t seem to be much difference in the portraits on left and right. It made me think of seeing things in (political) stereoscopy, of the left and the right perhaps not being too far apart, or perhaps being too close, rubbing uncomfortably together until fire begins.

MC: It’s important to me that the diptych portraits are different images. In some cases it is nearly imperceptible, but there is always a gap in time between the photographs. I like the idea of the pictures creating a kind of friction between political identities but can’t claim that as a motivation. Though I had some other reasons for arranging them this way, it is probably best to say that I did not feel the layout worked any other way.

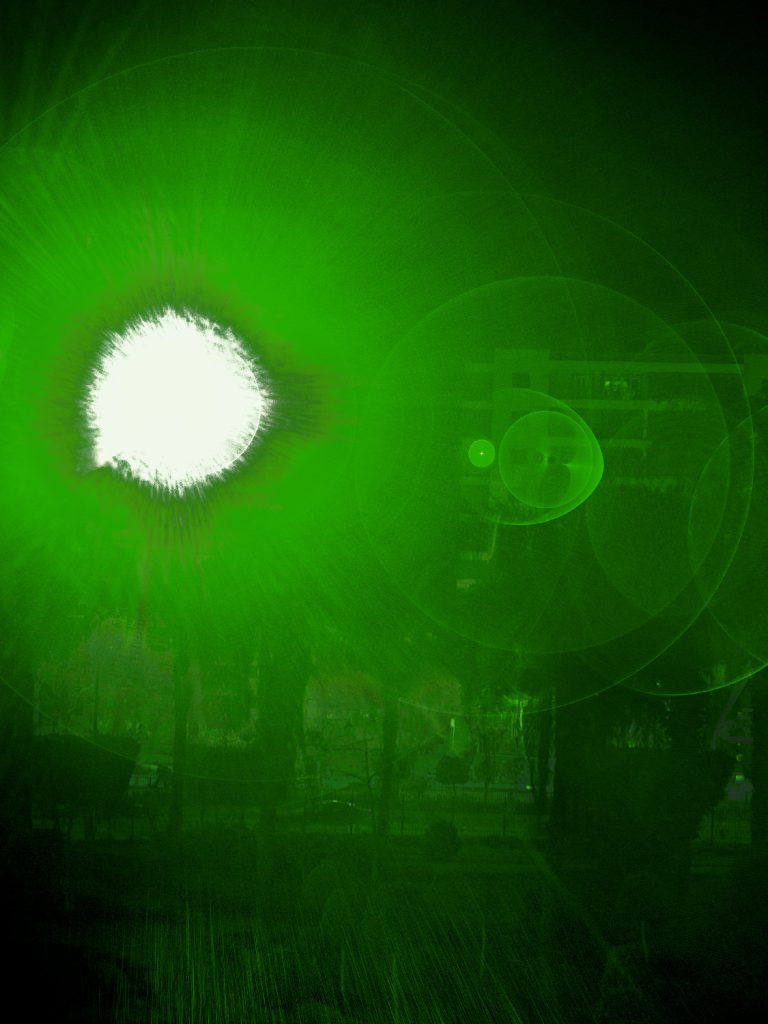

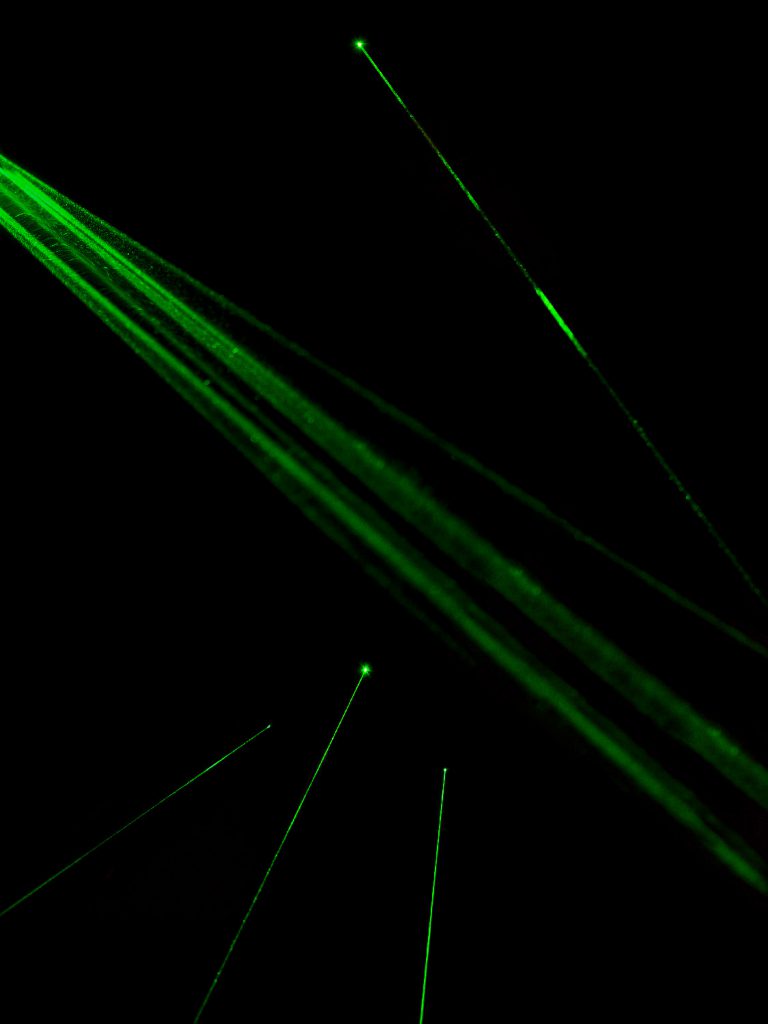

CK: Visual protest = laser

LB: The laser collages are particularly striking. As a continuation of question #6, did it ever become problematic for you, as an outsider bearing witness to a foreign conflict, to “manipulate” images (reality) into aestheticised abstractions?

MC: It didn’t. The alternative seemed far more problematic. It wasn’t in me—as an artist or outsider—to make a book that professed to be an authoritative account of the revolution, its underlying causes, and the competing interests involved. I felt the need to signal that I was approaching the situation with a high degree of subjectivity. The laser collages were one way of doing that. Those green beams of light were such an incredible aspect of the protests. For me, they represented Egypt’s attempted rupture with the past and became an important motif of the book.

Manipulation has been a feature of conflict photography since its earliest incarnations when Roger Fenton rolled cannon balls in Crimea and Alexander Gardner dragged the bodies of Confederate soldiers. Both were attempting to convey emotional truths that conformed to experiences of war they weren’t able to capture otherwise. I’d say my motivations were similar, but the only things I ever moved were pixels.

This is not to say the precedent is the resolution to the problem, but I don’t operate under the assumption that photographs have anything more than a tenuous connection to reality.

CK: Why are you interested in subjects that strongly suggest traces?

LB: Negative space as opposed to positive. Silence as a suggestion of noise, of upheaval.

MC: I think traces generate a different kind of identification, one that can be more palpable and experiential when narrative contours are not complete. This is something I absorbed reading a lot of early 20th century fiction in college.

CK: In an interview, you said your goal is the same as that of a novelist,

LB: …and that you take the same liberties an author might. What might these liberties be?

MC: It’s all the things we’ve been discussing, but essentially the liberty to refine and reorder experiences until they achieve a form that resonates with my sense of what it is right. Much of this takes shape in the voice of a body of work and the understanding that—like a narrator—that voice can be distinct from an author’s and potentially unreliable.

CK: For the audience to immerse and the desire to participate in political activity.

LB: Do you think it is too idealistic to think that a work of art could effect palpable change? Is it enough to just make art for this purpose? Or does the artist have to go further, organizing with communities rather than just creating art? Do you think that, once this line between creating art and immersing fully in a conflict is crossed, that the artist is no longer an artist but an activist? Are the roles more fluid? Seems like a simplistic binary, but I’m constantly surprised at how many people in the art world subscribe to it.

MC: The roles are fluid and depend on how individuals choose to engage with the world at specific moments in their lives. Some keep these spheres distinct and others attempt to merge them. You’re unlikely to hear me prescribe what an artist has to do, but that doesn’t mean I think they should be exempt from serving anything other than the constituencies contained in their minds.

That said, I believe art is ultimately a product of history and not a cause. While I think images can represent a key instrument of political participation by engendering emotional identification, I’m not convinced they can directly effect palpable change. But there is beauty and meaning in the struggle.

Fire in Cairo emerged from Egypt as an oblique and fragmentary document of revolutionary struggle. The book charts Connors’ uneasy engagement with the political turmoil that gripped the nation during its rapidly unfolding history. The complexity of the situation resisted comprehensive explanation, but invited metaphorical speculation. In his images Cairo reveals itself to be an enormous studio for social change, ripe with visual, sculptural and atmospheric residues of resistance.

He weaves these together with portraits of Egyptians from across the political spectrum and his own experimental fiction. The result is a book that careens between reportage, poetry and surrealism to heighten the tensions between beauty, threat and historical consequence.

The publication won the International Center of Photography Infinity Award in 2016.

Matthew Connors (b.1976) is a professor and Photography Department chair at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston. He received a MFA from Yale University and a BA in English Literature from the University of Chicago. His work has been exhibited internationally and can be found in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Yale University Art Gallery. He lives and works in Boston, MA and Brooklyn, NY.