Oriol Maspons

Interview by David Garcia-Casado, Coordinator Jordi Segura

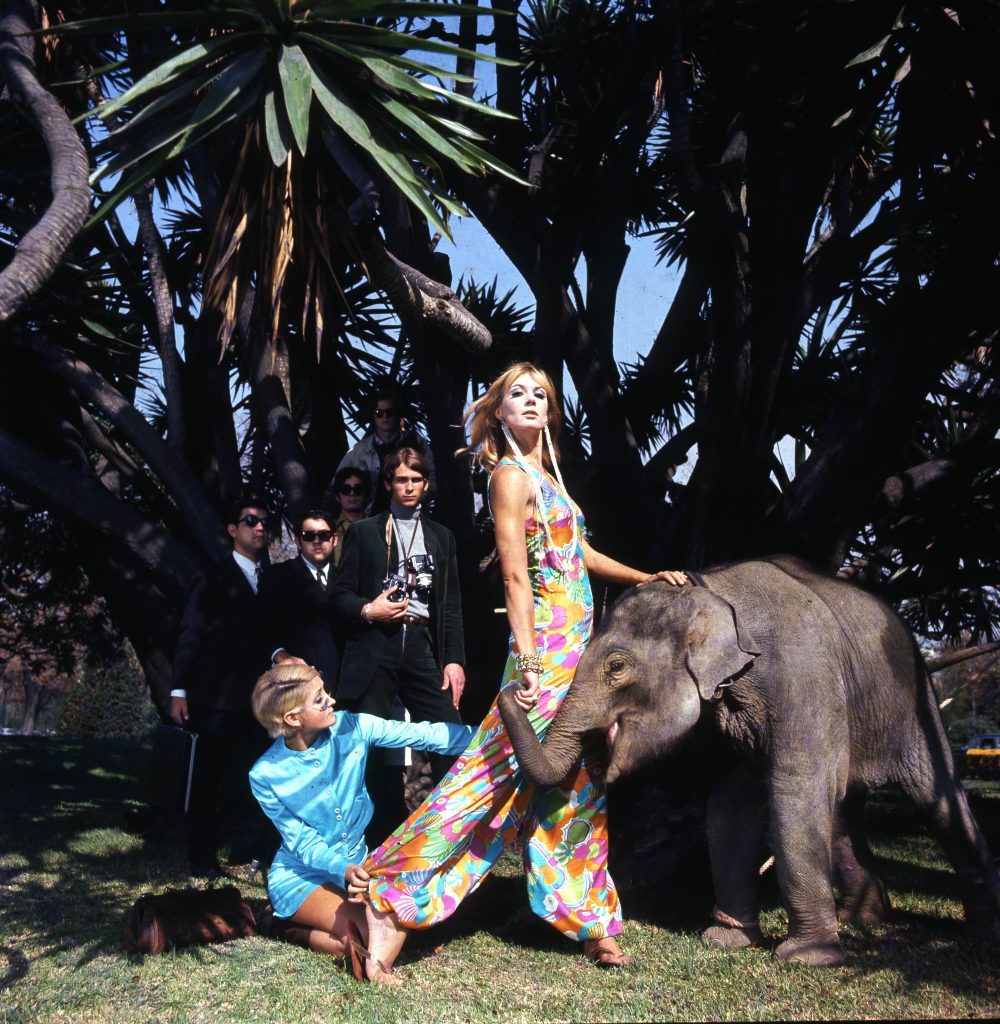

Oriol Maspons is a photojournalist from Barcelona, Spain. He developed his work in the 50s, the golden era of editorial photography, when he worked for international fashion magazines with other photography masters like Brassai, Cartier-Bresson or Doisneau. Simultaneously, he documented through very suggestive images the slow but fascinating modernization of Spain in the Franco era, which was sped off by the death of the dictator in the seventies. Together with a group of artists and intellectuals from the time he was considered part of the Gauche Divine movement and Bocaccio, exploring a new world of personal and creative freedom that his work still invokes and provokes.

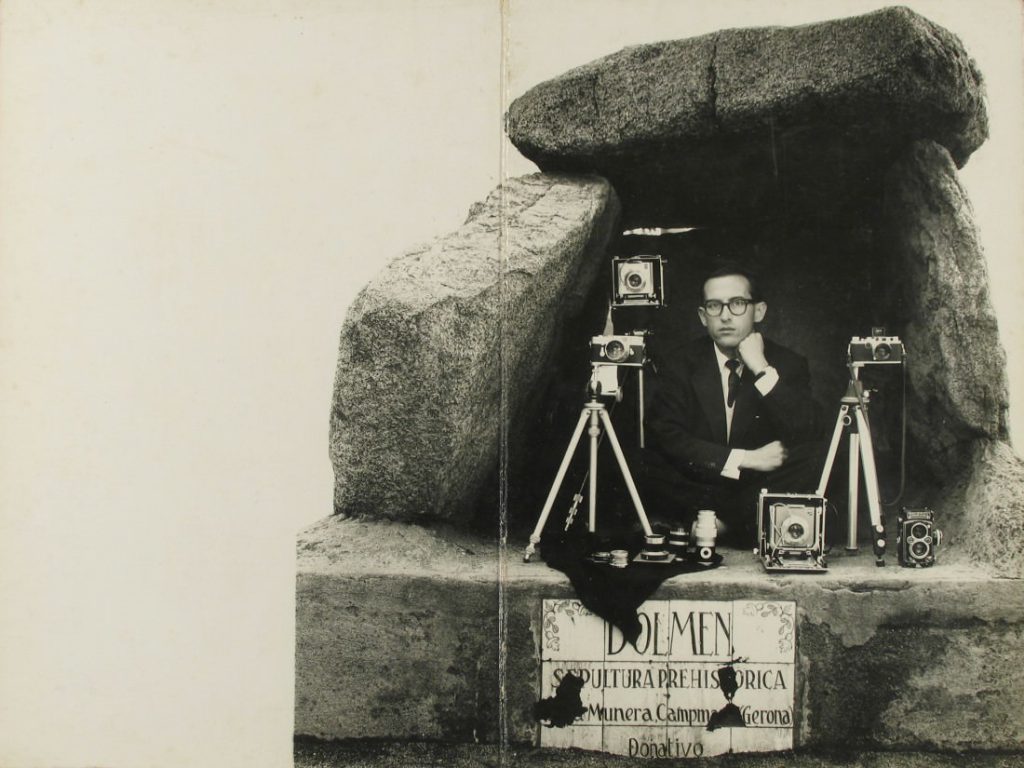

D. In an old self-portrait you pose, together with an amazing collection of photographic cameras, inside a dolmen, a prehistoric tomb. Looking at it now, it seems to me like an ironic instant on the disappearance of old analog techniques. I'd love to hear what the original purpose for that picture was?

O. That picture was a Christmas card I sent to a friend, it was taken in Gerona, Spain in an old burial dolmen. I did it with my partner Julio Ubiña.

D. It seems unavoidable to ask you about digital photography. I read in an interview that you “hate” digital cameras. Do you still think the same way?

O. I don't use digital cameras and I never have. Like they say, if it's not broken, don't fix it. Analog cameras have always worked well for me. Basically, I am disconnected with this new technology because it came late in my life. The only digital camera I owned, my son took from me (laughs).

D. I have heard that you have mostly worked per assignment, is that right? Do you also take pictures other than commissioned ones?

O. I was paid only for published pictures, which was very common and probably still is. So, consciously and unconsciously, my colleagues and I created images with the purpose of seeing them printed in the media. In that regard, there is not such a division for a photojournalist, we are at all times alert to images that can be used and constitute our work.

D. Do you think that a good picture should shock the viewer or suggest?

O. For me a good picture has to inform the viewer. Give them a sort of information that is new in a certain way. Also, depending on the assignment, you look for one effect or another.

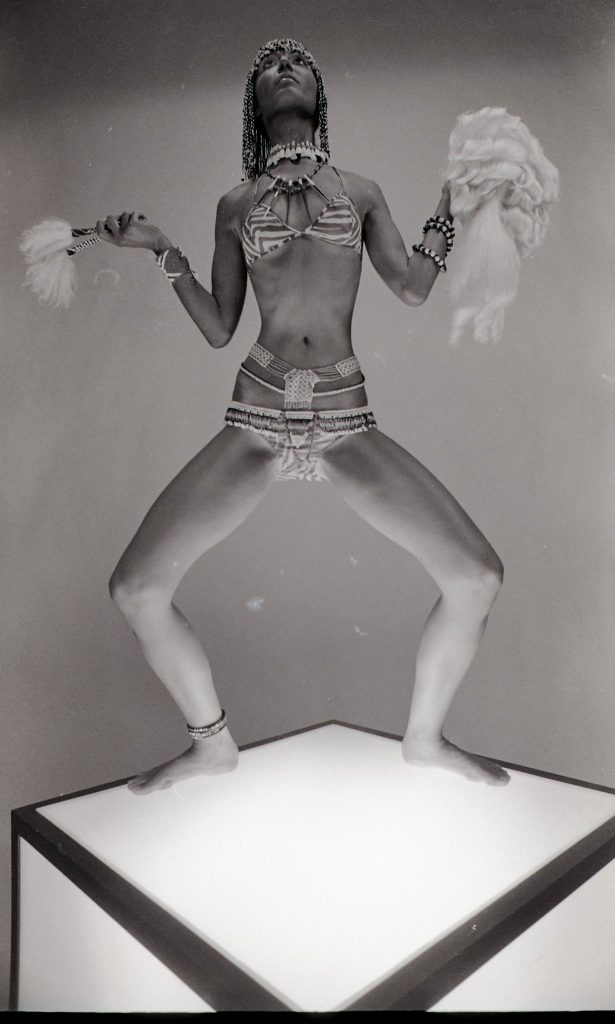

D. Usually, when you think about photojournalism, you think in terms of black and white photography. Why do you think black and white pictures look in a way more “real” to us?

O. Honestly, I think it's just because we are used to them. It's part of the collective memory since so many great photojournalists have worked in black and white. Perhaps because it is easier to develop...

D. To be a photojournalist, is is better to be unnoticed or to make yourself visible?

O. Well, I think most times it's better to be unnoticed (laughs).

D. Nowadays, some photographic prints reach very high prices in the market. What do you think of this commoditization of the copies?

O. This is a result of a tendency in the art market to balance the natural possible multiplication (and hence the devaluation) of the image as opposed to the uniqueness of painting. It is a way to balance the value and keep selling art.

D. New York, where I live, is a city that seems to be made for being photographed. Do you think some cities are more interesting for taking pictures, or is it more the people who live in the places that make them more interesting to take pictures?

O. New York is a fascinating city that I love, one of my favorite cities. The energy of the people who live there creates a unique atmosphere. The creative heritage of places is also very important. It is not the city itself what creates the energy, but the cultural influx and history which can support creativity in the right environment.

D. Can you speak a little bit about the cultural life you lived in the metropolises of the 60s and 70s: Barcelona, Paris, Rome, New York…?

O. In those days, the creative life in these metropolises was interconnected. We all knew each other and collaborated in projects together, sometimes out of friendship. For example, you would see Antonioni walking into my house and asking me to take some pictures...and I would do it. In my time, many photographers simply couldn't afford to be cinematographers, so we had to specialize in photography and make a whole movie in a single shot... (laughs)

D. What are you working on right now?

O. One of my latest projects is an anthological exhibition at the MENAC, curated by David Balsells, who is in charge of my photography archive in collaboration with Elsa Peretti.