The Office of Culture & Design

Clara Lobregat Balaguer With Audrey N. Carpio

Clara Lobregat Balaguer is an artist living in the Philippines, and to call her such is to consider the term in its most multidimensional form. She works out of her antiques-filled home office far from the city center, designing books, editing films, writing poetry, and tending to her plants. In 2010 she put up the Office of Culture and Design, an outfit that enables social art projects such as Kaid Ashton’s Home School, the Zamboanga Hace workshops for students in the conflict-ridden south of the Philippines, and other visual literacy events that engage with underexposed or marginal communities. She frequently collaborates with other artists who share a “common sense to know that finding new solutions involves throwing common sense out the window from time to time.” In collaboration with Carlos Casas, a Spanish documentary filmmaker—and a young Danish graphic designer turned Director of Photography, Stefan Kruse Jørgensen, Balaguer recently completed an experimental feature film called Lupang that tells the stories of an Ayta community displaced by the 1991 Mt. Pinatubo eruption. Clara talks to us about her film, her fascination with Filipino kitsch, and her own sense of displacement. And her bald head.

ANC: You recently shaved your head. What have you discovered about yourself baring your scalp?

CLB: I have discovered that the shape of my head appeals to people, that gay men dig women with bald heads, that femininity and hair are intricately linked but that the relationship can be supplanted with posture and movement, that I have a mole on my head and that most of the sensation of grime at the end of the day comes from having dirty hair.

ANC: It must be liberating, especially since we live in a long-hair-obsessed society. Has this affected your fashion in any way?

CLB: Not really. Maybe I wear more make up because it’s really easy to look like you’re terminally ill when you’ve a shaved head and have odd sleep patterns.

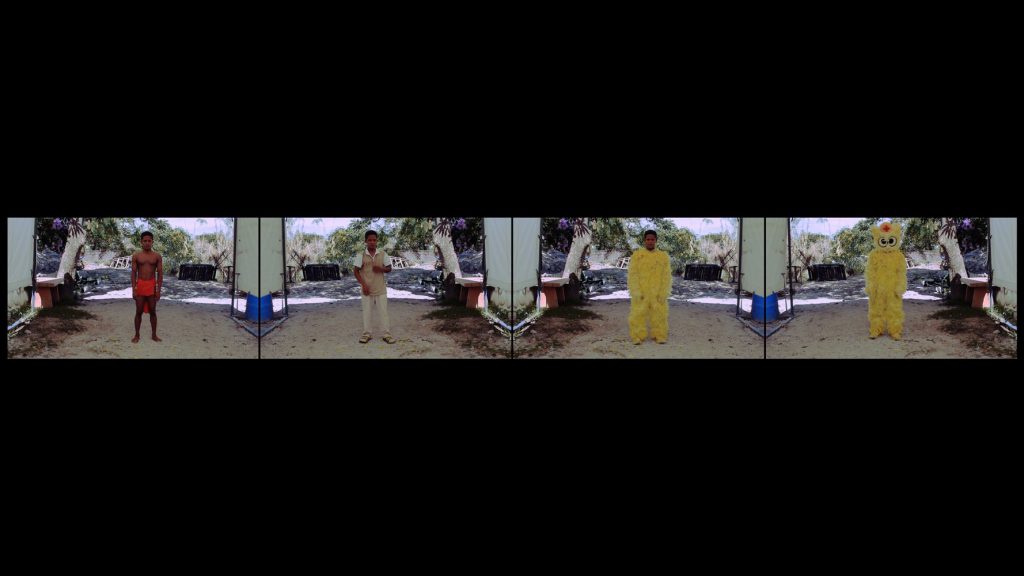

ANC: Let’s talk about your film, Lupang (The Land That), which was funded by the Earth Observatory of Singapore. It shows some surreal moments of touristic exploitation, honest karaoke, and personal, almost sacred instances of spirituality. What were some of the things you decided to leave out of the film?

CLB: Cooking lessons. An elder Ayta posing an open question to scientists that was so guileless and earnest it brought tears to my eyes: he asked how far the human eye could see, because from hunting knew he could only aim a certain distance with his bow, but then at night he could clearly see far, faraway the stars in the sky. The bulk of an intimate conversation with our neighbor, Marisa, on what women usually talk about when they get together at night, which is men. Twelve-minute long story telling exercises about the Aytas memories of the volcanic eruption in 1991, the one that displaced them from their ancestral lands and forced them to live near urban centers. The one that accelerated the process of their culture’s dilution. As is usually the case, leaving things on the proverbial cutting room floor is difficult. There were some moments that were very meaningful, but we either had to respect privacy, move away from stereotypes or keep to the focal themes of the film we had chosen to make.

ANC: As a poet, how would you describe Lupang?

CLB: Mindless noontime show / not a drop of shame, just

APPLAUSE / [blink] / APPLAUSE / [blink]

more more more of this dancing / more more more of this tourist attracting / more more more of your wealthy fat sexy rubenesque korean dollars / less less less human than they were / before before before you asked them to dance / like dolphins or bears or shamu / sham(eon)u / men of action, burning their fields / to spit(eyo)u / because they haven’t your permission to fight you.

APPLAUSE / [blink] / APPLAUSE / [blink]

Roman King has an exquisitely crafted vocabulary / and he only reached the third grade / Bert sings a song that could be written by the Eraserheads / and he also knows a few verses of the dororo prayer.

APPLAUSE / [blink] / APPLAUSE / [blink]

it was a delicate balance / on the weakest of finest of lines / between stupid flippancy of outsider / and profound frequency of time you did not set / and not knowing a single thing / and drones and beats and rhyme / without actually rhyming / without actually having anything to say / to make it better.

Let them eat patani. / Let them eat cake.

APPLAUSE / [blink] / APPLAUSE / [blink]

ANC: Having lived with the Aytas for close to two months, what can you say about the filmmakers’ (you and Stefan Kruse’s) relationship with the community?

CLB: I had never felt like so much of an alien as I did at the beginning of the shoot in Monicayo village. I was in my own country, but in some sort of alternate reality. At times, both Stefan and I were almost ashamed at feeling, keenly, the exoticity of living in a tribal village. It looked almost like any other village in the Philippines, but it wasn’t. Even though we built relationships with the people we filmed (and I hope that trust and respect comes across on screen), standing behind a camera creates a distance. Perhaps we didn’t spend enough time, on shoot, in order to become invisible. There was an awkwardness, a performative element, a lights-camera-action feel. It wasn’t dishonest, it was just a feeling of preamble to deeper relations.

Those deeper connections began after shooting, and generally happened off camera. The film was only the beginning, a shoehorn for us to enter the community. Also, the tactical character of the filming process was conditioned by the budget’s limitations. After shooting we continued our relationship with some of the Aytas as the project moved into the next phase, a cookbook of tribal recipes and a future livelihood project. Now I can say that I am starting to feel familiar (at times maternal, filial, or fraternal) with the community. I don’t know yet if I am an insider. That takes time. Trust is built and earned, not given away in front of a rolling camera. We are working on it, and the Aytas are thankfully being generous with their favor. (It’s my birthday tomorrow, and the Aytas are already texting me like crazy to wish me a happy birthday. Not even my dad remembers it's my birthday tomorrow.)

ANC: The head of Red Cross told me that the Pinatubo disaster, which happened in 1991, was worse than typhoon Haiyan, in a way. From your experiences what do you think we can learn and apply in terms understanding and rebuilding a stricken community?

CLB: The non-expert lessons I have learned from Pinatubo and other disasters large and small:

1) Ask before giving. Listen and observe before asking.

2) Nobody is oneself when they need and have lost. Giving of yourself is often an unromantic experience and ripe for mistakes and misunderstandings, in this context. In any context, actually.

3) Immediate disaster response requires people with a “muscle memory” that comes from have been in the field before. Situations are volatile, and acting with inexperience often adds complexity instead of solving. The urgency draws inexperienced people (like me) who, despite a lack of disaster muscle coordination, feel they need to help. We do not, however, have to help all at the same time. The same way that people have to get in line to receive aid, people should get in line to give aid in a scaled manner. As someone who reacts too viscerally to other people’s pain, I am perhaps not well-suited to the front line. The lesson I have to relearn constantly is that a natural disaster has an arc as long as it is tall. Response efforts are as crucial in the long as in the short term, contrary to what some humanitarian models have led us to believe. There is room for patience. And there is something to be said about finding places where crisis has become ingrained in way of life, where there is no logo visibility or media presence, where journalists kind of yawn unless it’s the 30th anniversary of something.

ANC: Last year OCD started a publishing house and design studio called Hardworking, Goodlooking with Brooklyn-based designer Kristian Henson. Tell me about some of the printed matter you’ve been working on.

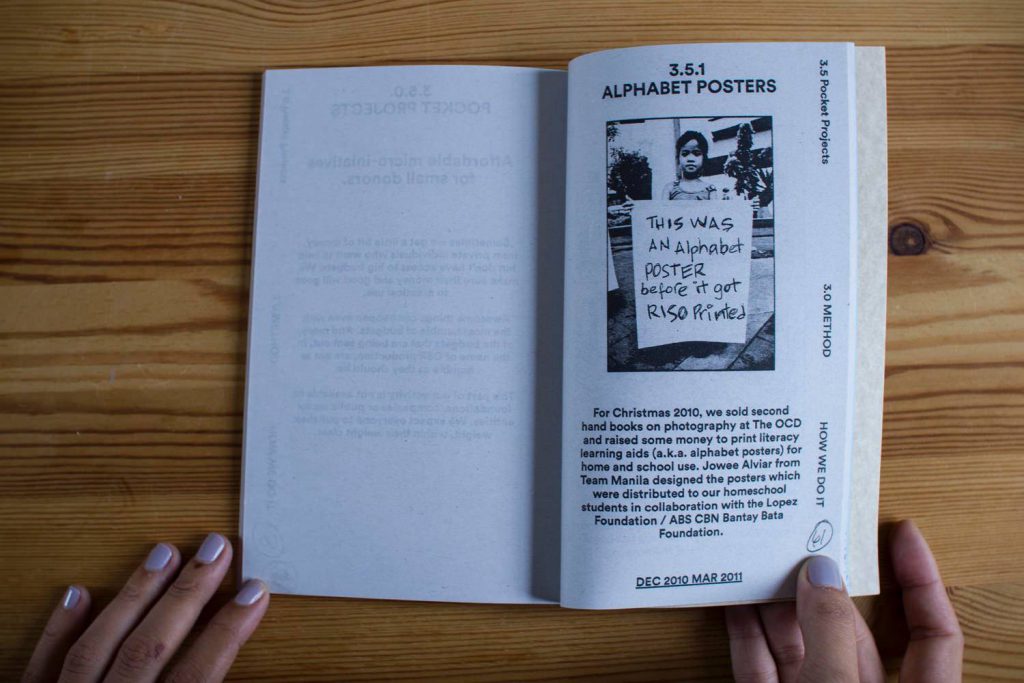

CLB: We recently printed the second edition of our RISO readers. I decided last year that all the projects completed at OCD should live on in printed format afterwards. While we’re getting all the material for each project together, we’re printing small project primers at “backyard” printers and copyists around Metro Manila. There’s a really interesting cottage industry around printing in the Philippines. Professional printing is too expensive and uncompetitive compared to the rest of Asia and the world, but itty bitty printers are more affordable as well as more interesting. It’s a learning curve for them to do this sort of book, but one that also gives our readers an edge when laid on a table next to any old Western publication. Not all of our books will be printed this way of course. We are now preparing issue number 3 of Edit magazine, and are set to print a book for Filipino artist Wawi Navarroza. Those we will do in offset and with a push for quality. But not all that glitters is offset, especially not in the Philippines.

ANC: SAIAO (Selected Artifacts in Alphabetical order), your product line inspired by the rural Filipino lifestyle, is set to launch this year. What kind of goods will you be selling?

CLB: We will be selling goods that I have found in my travels around the Philippines, for starters. The idea is to respect the products as much as possible, repurposing them just a tiny bit, but only to adapt the goods for “first-world” lives. Like there is this aluminum stove we have combined with 3 fighting cock leashes (cock as in rooster) to turn into a hanging planter. Eventually, we would like to work with the local manufacturers to come up with designs in collaboration with all kinds of people, but for now we want to keep it simple. It’s what we hope will keep our operations sustainable, and will become the added value that we provide to communities that we encounter. In four years of working on OCD projects, my grand realization has been deceptively simple: social challenges inevitably boil down to livelihood and the lack of it, for any group of people. So to truly contribute, I want to be able to provide an avenue not just for cultural experimentation or catharsis, but also for economic opportunity.

ANC: What draws you to native folknography, accidental design, the aesthetics of working class, and rural life?

CLB: Maybe I’m drawn to sariling atin [uniquely native or a concept referring to Filipino culture] because I have always been an outsider and insider in my country. Unfortunately the environment that I was born into was not necessarily Filipino-proud. In the first grade, I remember we would get fined 25 centavos for every Tagalog word that we spoke inside the classroom. Supposedly this was meant to encourage command of the English language. There were always veiled comments of criticism towards Filipinoness within earshot. I grew up with a sense of entitlement, superiority and otherness that was shameful. And that somehow could not be helped, or at least that’s what I tell myself. The Philippines was a volatile country when I was a child in the ‘80s and a teenager in the ‘90s. It was normal to live in fear of being kidnapped. It was normal to have school suspended because of a military coup. It was normal to feel that, outside of your air-conditioned bubble, people wanted to take advantage of you. And I suppose I processed all that post-colonial information in twisted ways, because I was not in the habit of contrasting information with adults. When I was older, I had the seven-year opportunity to make a life for myself abroad. It was that experience that taught me an important lesson: the feeling of otherness was not limited to living in the Philippines. It was endemic to me, and rejecting my heritage was rejecting myself. I belonged less abroad than I did at home. That’s where I began to look at my Philippine experience in a different light. Where I used to see negative and unremarkable, I saw sublime and brand new. I returned to Manila feeling almost like a tourist. I loved the city in exactly the way that I was learning to appreciate myself. You know how tourists look up all the time to observe a new place from all angles? That’s what I did when I came back home. And the sense of wonder remains, even five years after I moved back home. I cultivate it by moving as much outside of my comfort zone as much as possible.

ANC: You’ve shaved your head, obviously. What other things outside your comfort zone do you feel you need to do next?

CLB: I don’t really know. Life naturally progresses into discomfort zones without us having to help it along. Will wait for the next step to be revealed while walking in that general direction.

ANC: Having had past lives in television and advertising and what not, when did it coalesce for you that this—”to make art to write or design with the intent to contribute to the well-being of others”—is what you wanted to do with your life?

CLB: When my mother died. I had returned to Manila, sort of lost and wanting to be with my mother when it was confirmed that the cancer was going to win. When the battle was finally over, I don’t know... the umbilical cord had been broken for the second time in my life. And there was no going back to my old life. I can’t say exactly what it was, or when it was, but a feeling began to creep on me. The feeling that life was short and that the sense of otherness was my own fault. In my naiveté, all I could think of was to “help” people I thought were in “need.” It was rather “stupid” of me to assume I could “help” or that I was “needed,” but alea jacta est. There was a guy in the Astérix comic books that always used to say that when the pirate ship he was on inevitably sank in each episode. It means the die is cast. It’s been a strange journey on an often sinking ship, but I’ve committed to it, my ignorance notwithstanding, in every episode, book, project, life lesson. I always say that if I were a plumber, I’d be trying to put myself to good use through that. I’m nowhere near as handy as a plumber. All I can do is this sort of stuff, and I operate in that incomprehensible no-man’s land in between ideas and aesthetics and cheerleading and soapboxing. It may not be the most conventional approach to serving others, and working in the creative or artistic or literary field most definitely has a component of self-service. It’s not classic altruism, but it serves others and me better than where I was before, peddling phone plans and luxury cars and spirits and the dubious catch-all of lifestyle. Not that my former occupations were evil. They just for some unexplainable reason stopped being enough after I became a motherless child. Melodramatic and Piscean perhaps, but it is the truth as far as I can tell.

ANC: By the way, happy birthday dear Pisces! What’s your birthday wish?

CLB: Can’t think of an answer that doesn’t make me sound like a douchebag. lol. III