Anna Sörenson

"The Order of Things and All That"

With Lia Forslund

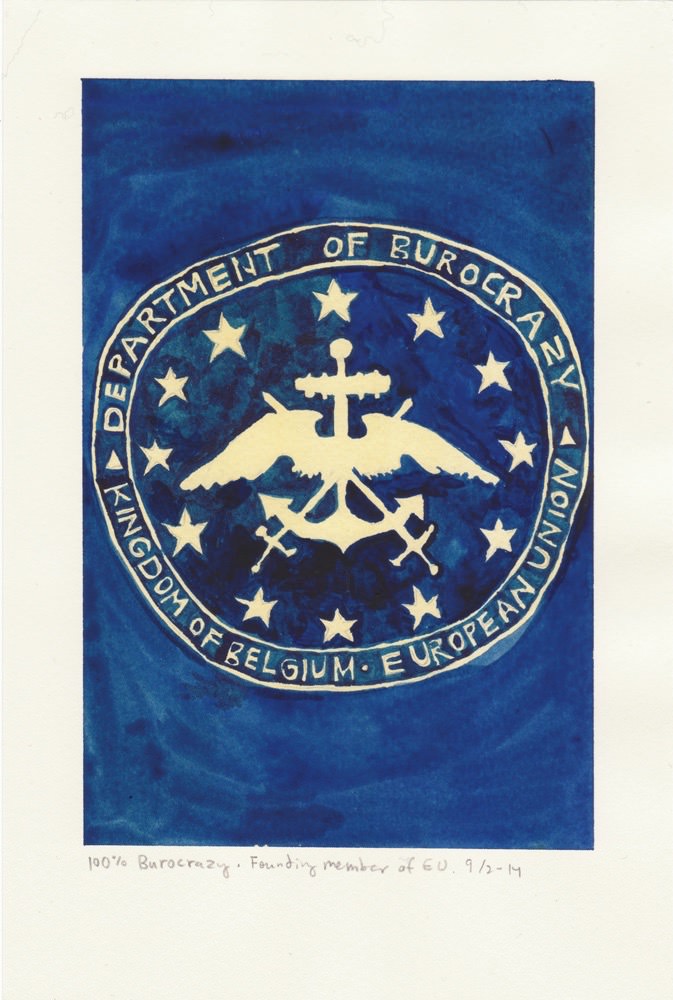

Anna Sörenson is a conceptual artist, a child of the 80s, a constant traveler and a nomad. When I was invited to her current home in Brussels, I envisioned archival desks and shelves filled with objects from her escapades around the globe. Surprisingly, her working space is quite the opposite of what I expected: twelve-foot ceilings and emptiness, apart from two plants, a computer, and a few sketches neatly lined up on the floor. Her work reflects her travels, but not the way in which you expect. She is a serious collector, but she is not collecting memorabilia; she collects to understand—articulating politics, philosophies, and values. Following her work from the early years in Northern Sweden to her graduation show in New York, I began to see a neatly composed pattern of ethics. From the well-pronounced paintings in “Valence in Everyday Objects” and “The Neverending Book,” to the rules of power and bureaucracy in “Your Application is Pending” performed in Stockholm, Brussels and Miami, Anna captures the complexities of our time through her own political systems, in what could be seen as a chaotic traveler’s journal of order, organizing and reorganizing the essence of her everyday practice.

LF: How do you think the extensive traveling in the past years have shaped your relationship with your work?

AS: When I was little I traveled a lot with my family and became accustomed to a constant shift in environments. Both my parents are writers, so they talk a lot about what they see and what they perceive. When I was young, I started to process what was around me, how one country was different to another. I think experiencing that as a kid, my notations became a way of understanding the world around me. I constantly try to understand how we behave in different contexts. The benefit of being a conceptual artist is that I do not necessarily need a studio to work in. I just work with my notebooks and my pencils.

LF: You have a piece of work titled the “The Neverending Book.” Why is the book format so important to you?

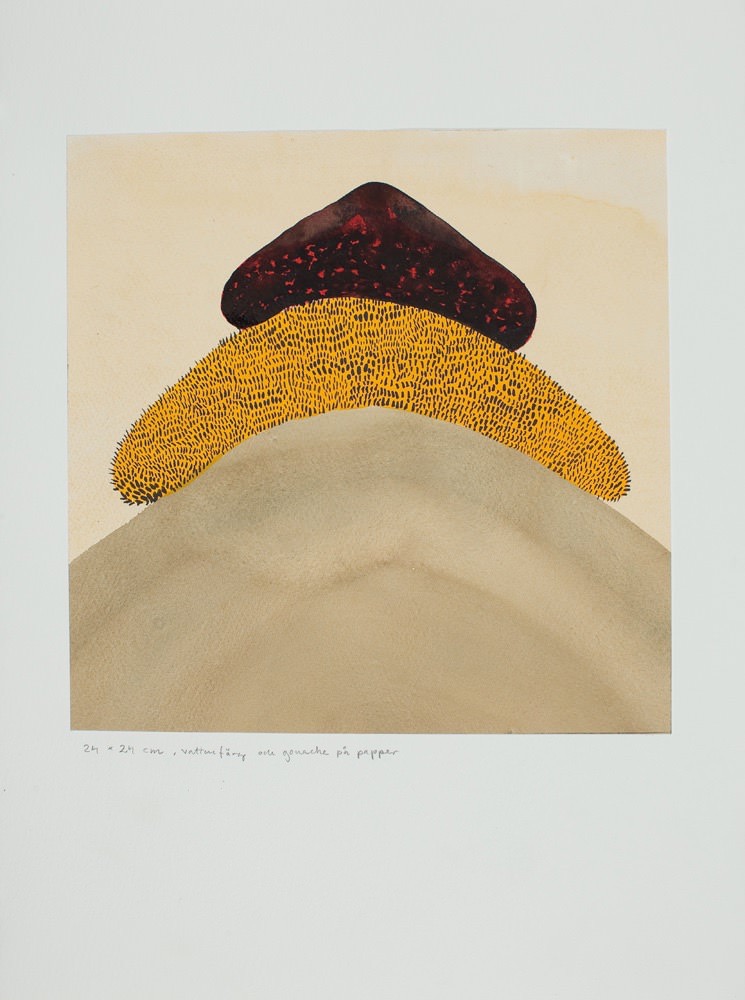

AS: When I think of it as a book, I think of the relationship between the reader and the narrator and the fact that the relationship is constantly unfolding, it is about all the shifts in time. Some of the images in “The Neverending Book” are repetitive, and others are random. For me the notations of time become the way to connect to the imagery. I am interested in the idea of the book as something you share with someone. There is something with the flatness too, the layers, on top of each other. It’s a very clear image for me—time, space, memory, and experience all layered in our body and minds. A beautiful word I use is palimpsest, the way in which experiences creates layers over time. To try to record constant change is an impossible task and that is also why the book is never ending, I can never complete the work, it will go on until I die.

LF: What does your workspace look like in relation to these layers? With “The Analog Database” and “The Neverending Book,” I imagined stacks and stacks of paper.

AS: In many ways I perceive the world as a very confusing and chaotic place. Ever since I was a kid, I have really enjoyed creating order. My desk is very neatly organized. All the pens are sharpened and lined up; even the pushpins are lined up symmetrically in a grid. Sometimes when I buy a bag of mixed nuts I can take an hour just to organize them by shape or color. This way of organizing, systematizing, and examining what I have around me is a way to find the potential in the shifts in between the objects themselves. There are so many ways of going about your life and I am simply not aware of all the possibilities.

LF: Looking at your work, the object is often central. Can you tell me more about your relationship to the objects themselves?

AS: I always collected things with great seriousness. As a kid I collected stickers, bookmarks, and stamps, but I also collected strange stuff, harder to organize, like the shavings you create when you sharpen a pencil—the little fussy things. I put them in jars to see what it looked like when it was organized, almost like a laboratory. I also had pet fish in different sized fish tanks, small fish in small tanks and large fish in large tanks. I do not know anyone else who thought it would be a good idea to have different tanks as it’s a lot of work to clean a fish tank, but the different tanks was a way to organize the species.

LF: After the performance pieces of “Your Application is Pending” you created “The Analog Database,” collecting material from the interviews conducted. Would you describe that as a lineup of people rather than objects?

AS: It’s a lining up of people, but it’s people in a specific context. They meet me at a performance in a format that they all have to relate to. There are set questions, following the regular format of bureaucratic interview. I did this performance in different countries and in order to keep a record, to see what happened, I used the analog database as a parameter. For me the notes let the interviews become visible. I have a much clearer understanding of things when I can see them.

LF: When conducting the interviews, do you notice the difference when people are lying from when they are telling you the truth?

AS: I can tell when they are lying or when they find something hard to answer. The cultural impact plays a large part in how you deal with authority. Miami for example, is the largest point of immigration in the United States. There is an evident formalized format of political language. We all have to obey it, it is super rigid, everyone knows that. When the Miami audience recognized the format and realized they were allowed to play with it, they expressed such joy to do so. When I performed “Your Application is Pending” in Brussels, the audience was almost too aware of the context, as most people in Brussels have worked with bureaucracy in some form. When they answered, they knew how to organize the information according to how important it was. It was much harder to tap into their production of fantasy, to make them want to play with the format. In Sweden, most people have a more subtle relationship with bureaucracy. With a small population, very close to the power, the Swedes have more friendly or familiar ways of talking within the bureaucratic setting. After the formal conversation people would continue, off the record, creating small talk or asking me to adjust something, almost as if there is some kind of general understanding—it’s boring yes, but it is probably boring for her too, so let's try to keep it sweet.

LF: You make it sound like a game: if you learn the rules you succeed. Do you really see it as a game?

AS: It is less painful if you see it as a game, but I am a privileged white woman and not everyone has the liberty to view bureaucracy as a game even if they wanted to. Having said that, I find it hard to play with authority, even though I have nothing to hide, I always get a little stressed, I am always afraid that I will do it wrong. I like to view people in bureaucracy as water in an espresso machine. You have to become steam, travel through the pipes, pass the curves, pour through the coffee and through the tiny pipe, you come out as another type of liquid, but you are essentially the same substance. This ability to transform yourself and push yourself through a labyrinth and still come out as good coffee in the end—it’s a skill.

LF: Your work with “departments” is clearly political. How political are the other projects in your full body of work?

AS: I think all my work is political. I believe the choices I make as an artist are extremely related to different philosophical, political and ethical conceptions. You are invited to complete something with me, like “The Neverending Book.” You need to be the narrator, you need to flick the pages. To me it’s a political choice to make the viewer take part and complete the work with me. I am not presenting a solution, but to act as a facilitator of the game, the play or the score—that is how I see myself as an artist.

LF: The way in which you organize your objects, pets and people, could the hierarchies and value systems in your work be seen as your own political system?

AS: There are always value systems when you organize something; I take the need for me to organize things very seriously. I value and organize materials in front of me to gain knowledge; however, I do not think there is one way of lining up in order to succeed. You can organize, organize again, reorganize and I think the potential lies in the constant flux. It’s a western conception that organizing things is about time, anticipating the speed of things. This idea of efficiency is really interesting, as the opposite often occurs; the system involves so many people, that people within the system do not know what the other people in the system are doing, so you cannot speed up the process. This grandiose idea that the western culture has, with one truth, one god, one way of organizing things is a fun conception, but it is not working, the system was so carefully designed, it does not apply to people anymore. I find this both funny and tragic, but it also says a lot about how we try to invent systems in order to understand the world and how difficult and misleading it can be.

LF: As a person who invents systems to understand the world, are you more fascinated by the system’s structure, or the time it takes to create them?

AS: I think it’s important to visualize the shifts, to show how crazy it can be when you try to apply the same kind of organization to many different things. If I applied the same kind of rules as I had to my stamp collection as a child, to the rest of the world, it would become evident how crazy that idea is. The made up systems often stem from the ideology or the idea that this system will make things better. That kind of absolutism is interesting to me, because we submit to it quickly. It goes back to Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish”–what will happen if you don’t follow the system? I am critical of how easily we submit. To obey the system, without questioning, enslaves people and creates hierarchies. This is probably the scariest course that the world can take. I think nothing good or humanistic comes out of that.

LF: Do you question your own systems, the ones you have created?

AS: Yes, all the time, because being an artist is a kind of privilege. As I get time to investigate these things, I constantly evaluate my responsibility to society as a person as well as an artist. With regards to my own system, no system has ever been constant; when a system is done it’s always time for reorganizing. As soon as I have organized all the stamps in the stamp collection after country of origin, I go on to reorganizing them again after motifs. No system can ever be representative in and of itself. It is the reorganizing that makes things appear for me.

LF: I was picturing you in a room full of paper and here you are with a computer and a few sketches. How do you envision your imaginary office?

AS: I have a clear image in my mind of what my dream office would look like, file cabinets and workstations. The office would be based on material, because I have to pick up and look at things. It needs to be three rooms though, one for the meeting, one for the organizing, and one for archiving. The audience is as relevant as my organization; therefore a meeting room is needed. My actions formulate the way I speak to my audience and how they perceive me. What I do and what I take agency for is the platform for our conversation between myself and the audience, and that relationship is what makes my work or research an art experience. III