What matters to Printed Matter

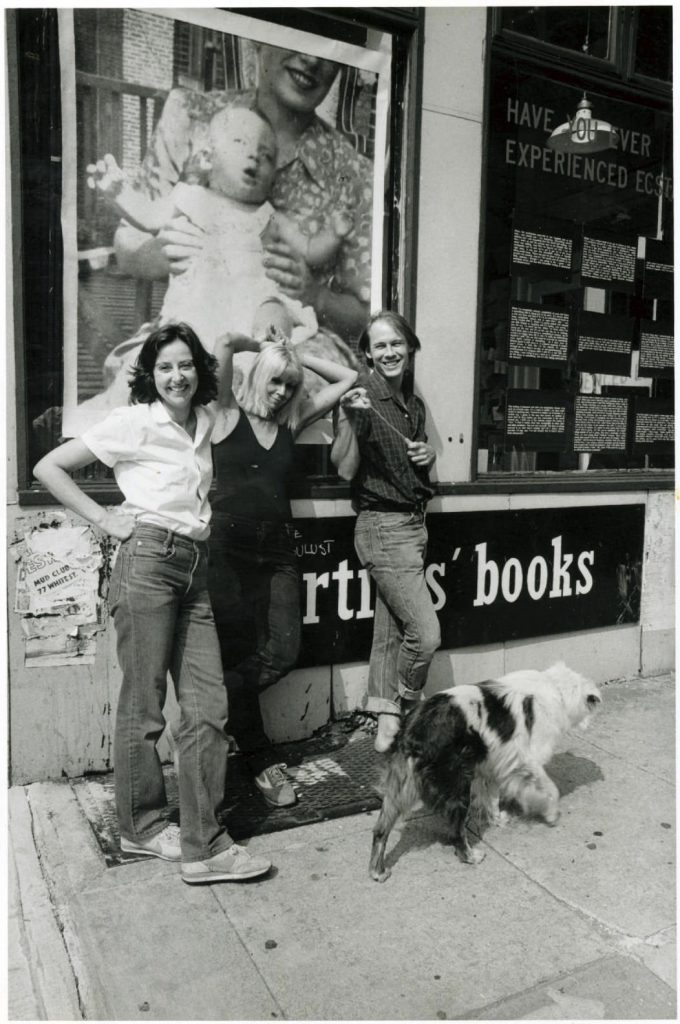

Printed Matter is the art bookshop by which all other art bookshops yardstick their success, whether they know it or not. A pioneer in the field of artists’ books and a nerve center for New York’s alternative arts world for four decades, Printed Matter's history was the subject of an exhibition and publishing project at NYU’s 80WSE gallery in December of 2015, entitled ***Learn to Read Art: A Surviving History of Printed Matter.*** The archival show was articulated in the form of a timeline that charted the organization's history, which is analogous to the history of artists' book publishing and the most important contemporary art currents from the 70’s onward, such as the alternative space movement, downtown NYC counter-cultural scenes and artist activism.

Learn to Read Art was a somewhat poignant show, as it exhibited only the portions of Printed Matter's archive that survived Hurricane Sandy's floods in 2012. As if to fill the void left by the loss of over 9,000 books and many other priceless artifacts, the exhibition was also made generative. A publishing residency complemented the visual installation, fully equipped with a bookmaking studio where artists Mary Ellen Carroll, Jesse Hlebo/Swill Children, Juliana Huxtable, Red76, Research and Destroy New York City, and Josh Smith produced publications on a photocopier, a risograph, silkscreens and letterpress. A satellite bookshop and chronologically arranged reading library were set up on-site, allowing people tactile ownership over their exhibition experience. And a panel discussion at Judson Church saw Printed Matter's founders dispensing wisdom and shooting shit valuable in equal measure to publishers, art historians, cultural actors, anarcho-zinesters and feminist leaners.

The words of Jonathan Berger—director of the 80WSE Gallery, assistant professor of Art and Arts Professions at the NYU Steinhardt School, and co-curator of the exhibition—frame the windows of conversation and tiny pictorial histories that follow: "Printed Matter remains unique in its ability to democratize the field of contemporary art. Where else in NYC does an artist book by Ed Ruscha sit next to a zine by a teenager from rural Ohio?" More than just a bookshop or a set of art book fairs, Printed Matter was, is and (soon at its fancy new location in Chelsea) will carry on giving the most elegant of fuck-yous to the high art world and its exclusionist tendencies. So elegantly executed it sounds more like a you're-welcome. So resoundingly necessary the art world has practically said, "Thank you kindly."

10 QUESTIONS FOR MAX SCHUMANN

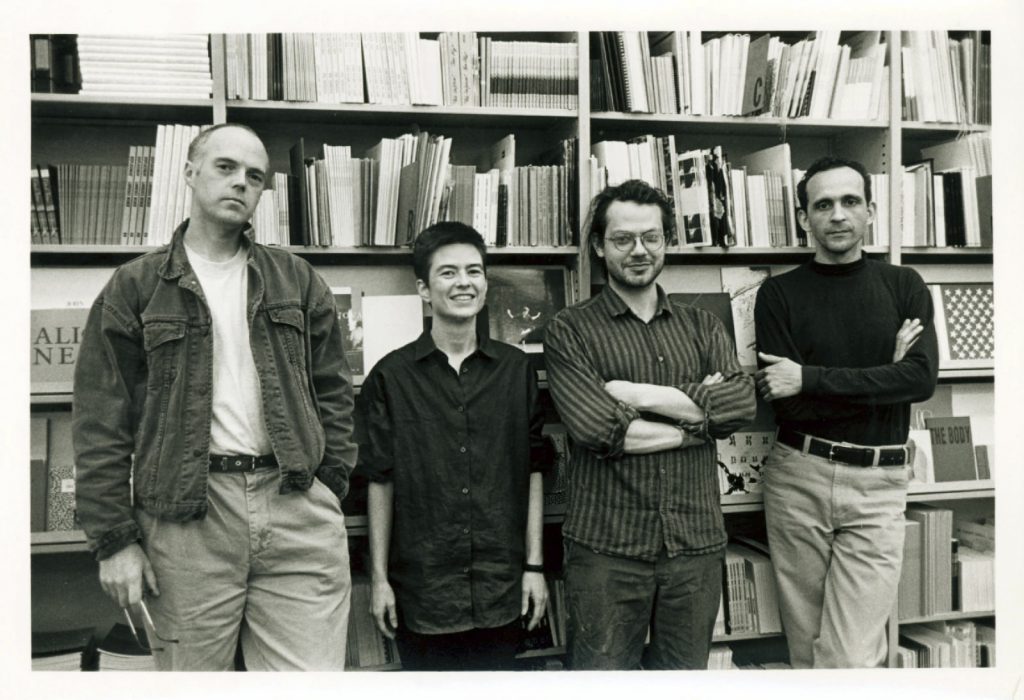

Max Schumann is Acting Executive Director of Printed Matter, where he has been working for the past 22 years. He is also a working artist.

(1)

LB: You have said that the retail portion (bookstore) of the Learn to Read Art show at NYU is implicit and integral to the purpose of the artists’ book itself: the search for an alternative profit structure for artists. Printed Matter, as a retail outlet for these publications, has struggled with the fulfillment of its initial goal to be a self-sustaining company and has embraced its identity as a non-profit that relies on external support. Where does the relationship between self-sustainability, profit politics and your brand of social practice stand for Printed Matter?

MS: When Printed Matter was founded it was set up as a for-profit business. Not that the founders had any expectations of getting rich off of inexpensive, (relatively) large editioned artists’ books. They rather hoped to create an economically independent model for the production and distribution of experimental art in published form. Within a year they realized that this was not the case and filed for non-profit status.

Originally established as both publisher and distributor, Printed Matter was confronted with the reality that contemporary artists were not economically self-sustaining. As Lucy Lippard lamented in an essay she wrote around 1978, the problem with artists’ books being an affordable and accessible form of contemporary art was that they were “contemporary art,” much of which is highly specialized and really of interest only to a narrow, educated, privileged class. Printed Matter still has boxes filled with some of the artists’ books published in the 1970s, and some sell at the rate of maybe a handful a year at their original prices of five and six dollars, meaning they will be in print for several hundred years to come! Affordable and accessible, yes, but if they are not desirable, then what’s the point? This is an internal contradiction that will always be partly true of contemporary artists’ books.

But I say that this contradiction is only partly true, because relative to the “high” art market, where singular works sell for exorbitant sums, artists’ books are extremely successful. Some are selling through editions of 500, 1000, 2000 or more, reaching a much broader public than the high art-buying class. It remains mostly true that artists’ books do not automatically provide an independent economic model for cultural production. For many of the hundreds of artists’ book publishers at the NY Art and the LA Art Book Fairs, this enterprise is a labor of love. Many are paying out of pocket or finding other subsidization to support their passion. At the same time, many of the new generation publishers are exploring and honing the economic models of their publishing practices towards sustainability.

And if you compare that model to the high art economic model, I would argue that the former is much more of a real economy then the latter, based on the costs of raw materials, industrial production and distribution. A painting being valued at one million dollars has absolutely no relationship to its social-use value. So high art is much more of a fantasy economy and is, also, or more so, largely subsidized.

(2)

LB: The flood that occurred after Hurricane Sandy destroyed much of your archives. How has the organization responded to the crisis?

MS: The Hurricane Sandy flood was an eye-opener for us to become more self-conscious of our (institutional) legacy. Part of how we got to this realization lies in the tremendous outpouring of support, humbling and at the same time vindicating. The extraordinary generosity of individuals, the non-profit arts community, the commercial art gallery community, foundations, and even the government made our full recovery possible.

When we started pulling the inventory that had been stewing in floodwaters, we quickly realized that stored behind it, in the basement, was Printed Matter’s archive. While the books were ultimately replaceable, in that other copies existed elsewhere or ultimately could be reprinted, the archive was not. It encapsulated close to forty years of our institutional history in the form of documents, correspondences, administrative memos, financial records, and so much programming ephemera. It is the archive that really tells the story of Printed Matter, not just as part of the history of artists’ books but also that of contemporary art itself. It is furthermore a documentation of New York City’s cultural memory.

While we frantically tried to secure an emergency conservation company, which was not easy as they all were contracted with big institutions and responding to their conservation needs, I set up a triage area, probably about thirty feet of sidewalk where we laid out all the material from the archive. Because the conservation fees were so expensive—I think over $200 a box—I was told to identify about thirty boxes of the most important material from what had been more than sixty boxes before disintegrating in the floods. This was like a life-and-death crash course through Printed Matter’s archive.

Because I’ve been with the organization so long and was familiar with much of the material, we were able to identify the most important stuff. But we did end up throwing a lot away, the stuff destroyed beyond repair, material we identified as duplicates, stuff that just seemed less interesting. It’s the latter I’m most worried about because after going through the surviving archive, we’ve realized that it was sometimes the little incidental pieces of ephemera that really told a bigger story, sometimes in relation to each other.

(3)

LB: Any particular items that you wish had survived?

MS: Probably the saddest disappearance, in my opinion, had the lowest dollar value. We lost probably over 10,000 of our Artist & Activist pamphlet series (on top of approximately 9,000 other book casualties). Initiated by former Printed Matter director AA Bronson and funded by the Gesso Foundation, this series of 20 pamphlets were distributed for free and thus were not technically considered inventory. The 20th volume, the Zone, by Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, was completely destroyed in the flood except for one desk copy I had upstairs. I had met the two artists in Ramallah, where I did a series of Printed Matter presentations, and had invited them to do the last booklet in the series. The pamphlet had just been printed and we were waiting on shipping arrangements to send half the edition to the artists for distribution. So all of the boxes were in the basement, except for that one copy.

(4)

LB: And the most interesting archaeological finds?

MS: There was an old rebuttal written in response to Printed Matter not being awarded a grant for the window installation program because they did not have receptions for the artists. In the letter, both Lucy Lippard and then-director Nancy Linn emphatically stressed that the installations were intended for the working class public and pedestrians of that area, not for art-world schmoozers (in so many words). There was a folder full of newspaper and magazine clippings, dated just a few years later, about major art philanthropists—leading industrialists, entrepreneurs and other assorted capitalists—with names encircled and mailing addresses and phone numbers penciled in. These two bits-of-pieces are quite articulate on their own.

(5)

LB: Lippard, who early in Printed Matter history was in charge of curating the window displays, has said that these storefront installations were not conceptualized to attract customers but to communicate politically and socially oriented messages. Is this still part of the curatorial guidelines for the window-installing artists, or has the social element been reduced to the window as a parcel belonging to public space (not necessarily even for the working class, since the gentrification of Chelsea)?

MS: The public window program that Lucy curated from 1979 to 1989 was a remarkable survey of political and activist art of that period. Specific social themes such as nuclear disarmament, gender stereotyping and misogyny, real estate and gentrification, the system of incarceration, US involvement in Central America, and police brutality were specifically addressed. Other windows were more conceptual. Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince—some of the leading artists of what’s come to be known as the Pictures Generation—all did early-career window installations. Julie Ault, one of the founding members of the Group Material artists’ collective and a member of Printed Matter’s board, curated the windows briefly after we moved to Soho. These also had political/critical content.

Currently, Printed Matter’s window installations are mostly curated in conjunction with other programming, usually in tandem with an artists’ book exhibition or newly launched title. So sometimes there are clearly identifiable politics, but sometimes not.

(6)

LB: Clive Phillpot mentioned something in the panel discussion of the Learn to Read Art program that was quite suggestive about the aesthetic of the Printed Matter store itself. It was something to the effect of the store being “a jungle of leaves, a texture of excess” that evokes a sense of the space belonging to a large and extended community. The community’s ownership manifests in its members being able to leave their own mark on the space and perceive the presence-marks of others who have gone before. Romanticism aside, there is an obvious need to provide ample space for Printed Matter’s growth within your new Chelsea address, designed by Handel Architects. To what point is that signature textural universe described by Phillpot—in some ways a protest against the hallowed white walls of art institutionalism—something you and/or the architects have taken into consideration for the new space?

MS: I think that architectural design can only go so far. Mark Krayenhoff, who designed our current space, did a brilliant job, using common, inexpensive industrial material in innovative ways. Handel Architects are basically following those utilitarian principles, which are also Printed Matter’s, but ultimately what defines Printed Matter is the content, the books themselves, as in you can’t judge a book by its cover! Here’s a snippet I wrote about visiting Printed Matter in 2009 while I was on a sabbatical, which kind of sums it up for me:

“The first time I came back down to the city I headed out to Chelsea to pay a visit to Printed Matter. On my way, I leisurely stopped in at a gallery to check out an exhibition of an artist whose work I admired. It was conceptual, politically-themed stuff, stuff that I usually like, but somehow the experience felt remote—the gallery was inhospitable, and the work felt inaccessible, both symbolically and materially. And then a few blocks later, when I entered Printed Matter it was like a full body experience. The place was buzzing: books, posters, prints, ephemera were exploding out of the shelves and off the walls. There were a healthy number of visitors, some poring through books, others talking amongst themselves, responding to the books, each other, the environment. I thumbed through some new arrivals, so much stuff to see, so much information to take in. Here was a real art practice, an environment where the consumption of the material is a social and collective activity, where there is both a physical and informational exchange between viewer, artwork and artist.”

(7)

LB: Given that the history of Printed Matter and that of artists’ publications is intertwined, it would seem like a natural progression to see Learn to Read Art’s archival archaeology translate into a book of its own. It’s important to consolidate and disseminate this knowledge while Printed Matter’s founders and gatekeepers are still very accessible and involved, right?

MS: During the preparation of the Learn to Read Art exhibition at NYU, we actually started cataloguing a lot of the material as we do want to produce a publication on our history. We are also seeking to travel the exhibition internationally.

(8)

LB: You have said that publishing original content is going to be a priority on Printed Matter’s agenda in the coming years. What is going to be your strategy for selecting books to print? Is it going to be for consolidated artists or are you looking to include the voice of the little book maker?

MS: Right now, we are concluding our latest Emerging Artists book series of six new titles. We had an open call for proposals from which the final publications were selected by a jury. We are seeking funding for a second round, to be implemented on a similar model. In addition, there are several backburner publications related to past exhibitions that we need to complete.

Outside of this, we publish artists’ book by invitation only. We do not accept unsolicited proposals, in contrast to our submission policy for already-published artists’ books (for potential sale at Printed Matter store and website) which does accept unsolicited material.

We try to identify both artists with a longstanding or active publication practice, as well as artists who might be less well known but whose work we think might translate to book form in an interesting way. It’s also a priority for us to have a mix of young and old, established and emerging, etc.

(9)

LB: What is Printed Matter’s position on the biennale-fair trend as an overly globalizing force in the art world?

MS: Similar to the internal contradiction I discussed in the outset—that artists’ books simultaneously fail and succeed as an accessible and more democratic form of art—I think that Printed Matter has been on an inside/outside position in respect to the art market since the very beginning. In 1976, when Printed Matter was founded, many of the artists’ books being published at the time were by commercial galleries. Many of the artists were well on their way to establishing successful careers, Sol LeWitt among them. LeWitt’s success never conflicted with his interest in the artists’ book form. While he did make some deluxe limited editions, he continued making large editioned, affordable books for pretty much his whole career. Likewise, I think Ed Ruscha provides another interesting model. While his artist’s books are now highly sought by collectors and fetch high to very high prices, for several decades while the books were in print, a majority of them were sold and circulated affordably. It was not uncommon in the 1980s and 1990s to come across classic Ruscha books in the sales bins of used bookstores for five dollars or so. So while, in the case of Ed Ruscha, market fetishism triumphs in the end, that does not negate that, for a while, the books did do what was intended: widely distribute his artworks through a system other than the art marketplace and in the manner of everyday commodities.

Printed Matter does participate in some of the contemporary art fairs because that audience is one of our constituencies. But we also have many other constituencies outside of the fair crowd. In the NY and LA Art Books Fairs, the participants range from blue-chip galleries like Gagosian and established commercial and institutional presses (like DAP and MIT press) to decades-old independent artists’ book presses and startup zine collectives by twenty year-old anarchists. It is this diversity and inclusivity that is unique to our book fairs in the contemporary art fair landscape.

(10)

LB: I hope you weren’t annoyed by that last question, which comes not from a place of antagonism but from a real exhaustion with the posturing that dismisses, without categorization, any work that actively critiques neoliberality or proposes horizontal access to art as ineffective. Because the works, as art actions, belong to the system or market being criticized. I understand, of course, that the posture and the questions it raises are legitimate.

We are far from the 70s, when Printed Matter was born and artists were full of utopian hope in art’s ability to effect social change. I asked the question because I came across a Frieze Magazine review of an exhibition you did in 2005 at Taxter & Spengemann. Among other propositions in the show, one of them was pricing the works in affordable tiers, a nod to the Cheap Art movement initiated by the Bread and Puppet Theater group in 1982.

Nearly ninety years after progressive modernism and its pitfalls; thirty-odd years after the activist turn of arts in the 60s and 70s; forty years after Printed Matter’s birth as a response to elitist art insiderism; twenty-three years after the Cheap Art proposition, and ten years after that review of your show, critique of socially engaged art projects has not progressed much from that initial exposition of the basic quandaries of art market meets social agency. It seems we have not moved beyond stating the problem, but rather are wallowing in it, or simply not proposing convincing enough answers. I was hoping you might shed some light on the matter, from where you stand as an artist and curator.

MS: I was not at all annoyed by the question. I think we need to be honest about our relationship with the powers, including our complicity in privileging exclusionary hierarchical structures.

I guess what bothers me more than the critiques of critical/political art work being problematized by the very fact of its being art, are the critiques of non-critical/political art that doesn’t examine how highly political/ideological that work actually is by what it (and the critique) doesn’t address. There is a healthy suspicion, even antagonism, between outsider activist art and insider critical art. The former are too idealistic and reductive, and the latter are too inaccessible and institutionally beholden. No matter how “radical” the critiques are, they are essentially part of the bourgeois intelligentsia.

The stuff that’s in the middle and that shifts between those positions is where interesting things are happening. A lot these activities, actions, and collectives are not necessarily identifying themselves as art to evade the pitfalls of that association. I think the Occupy Wall Street movement is a fascinating example of this. Some of the founding organizers were artists, former artists or contemporary art educated people. It was a social, political, economic and cultural uprising that broke through the corporate media induced hallucination that class doesn’t have consequence, especially in the United States. Whatever the problems and contradictions of the Occupy Wall Street movement, it was a threat to the elite, as manifested by state violence and repression. Occupy was only the U.S. iteration of an ongoing revolt against neoliberal corporatism, which is international in scope. The problems that cultivated this remarkable outpouring of activism and intervention have not gone away. There are and will be plenty of opportunities to make real political and critical “art,” “cultural work,” or whatever you want to call it, in the future. I think that artists’ publishing has a critical role to play in how this unfolds.

7 QUESTIONS FOR SHANNON MICHAEL CANE AND JORDAN NASSAR

Shannon Michael Cane and Jordan Nassar have been running both the NY and LA Art Book Fairs as co-curators and coordinators. Cane previously worked as an editor and publisher for the queer art zine They Shoot Homos Don't They, which he put forth from his native Australia whilst writing for other magazines such as BUTT, Little Joe and Straight to Hell. Nassar is a Polish-Palestinian artist from New York who uses needlework, heritage textile patterns and Photoshop to recontextualize manifestations of place and identity in a post-internet world.

(1)

There was an exponential jump from forty exhibitors in the first year of the NY Art Book Fair to 120 in the second year. The growth has been consistent since. In 2014, the NYABF counted 360 exhibitors from twenty-nine countries and an audience of 36,000 people. In 2013, the first LA Art Book Fair opened to similar success. In what ways has the popularity of the book fairs been a tipping point for Printed Matter's expansion or sustainability? Has it brought the organization closer to the elusive goal of self-sustenance?

Of course the NYABF and LAABF are, in part, fundraising events for Printed Matter, and every bit helps in bringing us closer to the goal of self-sustenance. That being said, the NYABF and LAABF are far more influential in achieving other missions and goals that Printed Matter has had since the beginning—namely, the dissemination, understanding and appreciation of artists’ books. As a result of the fairs, the community of publishers, artists, distributors, collectors and artists’ book fans has been both increased in size, as well as solidified as a real community of people working together and appreciating each other’s work. The growth of the fairs in both the number of exhibitors as well as the number of attendees speaks to this phenomenon, and the fostering of this community is absolutely the most precious fruit of our labor, with regards to the fairs.

(2)

Printed Matter and, by extension, its book fairs are a democratizing force in the art world, juxtaposing unknown and established artists on the same platform and allowing an audience affordable access to buy and consume art. What kind of feedback has this posture generated from the more institutional contemporary art community, whose iconic venues you trespass yearly and elitist ideals you openly decry?

There’s no negativity here. We are constantly welcomed and supported by our friends at commercial organizations and institutions. People in the art world who truly appreciate the artist’s work are always enthusiastic about what we’re doing and what we’re showcasing, as we are in what they’re doing and showcasing. We are so supported by galleries and institutions, especially those that work with the same artists that we do.

(3)

The Printed Matter fairs have had global effects, spawning a host of homage art book fairs all over the world. What curatorial advice would you give to those thinking of putting up their own art book fair?

Curatorial vision should and does vary depending on who is doing the curating, and that’s to be expected. The only recommendation we would give is to be firm with the definition of what an artist's book is. Catalogs, monographs and literature need to be kept separate to help the visitors understand how artists' books differ from other publications—how they are works of art in themselves, as opposed to publications about or showcasing artwork.

(4)

The Norway Country Focus section of the 2014 NYABF fair was put together with a conscientious on-location research period fully supported by the Norwegian diplomatic corps in NY. How different was this process from other country-focus experiences in the past? Is this the model you would like to follow in the future?

Each Country Focus room we do differs depending on the organizations that happen to get involved. For the Norway Focus room, yes, we were lucky to have generous support from the Norwegian Consul General in New York, and we were able to go to Norway and meet with artists and publishers so as to curate the room. However, this is only one of many ways that a Country Focus room can come together. Others, such as the Swiss Focus a few years ago, come together naturally due to a tight-knit community of publishers in that country. The Country Focus rooms tend to be a natural development each time they happen, with the potential for a constellation of government, non-profit, public and private groups to get involved around each room.

(5)

Aside from your work within the Printed Matter store and the fairs you organize, your travel schedule is hectic with trips to other fairs such as Paris Photo, Art Basel, Art Los Angeles Contemporary and Material Art Fair Mexico. What kind of insight have these experiences as exhibitors brought to your position as organizers, or vice-versa?

It’s always good to experience fairs as an exhibitor if you yourself organize a fair. It does, of course, help us provide for our exhibitors as best we can, being able to preempt their needs and wishes. And, vice-versa, we hope we’re gracious exhibitors, knowing what is to be expected from participating in a fair, and what is out of the organizer’s control.

(6)

How does the democratizing ethos of Printed Matter come to terms with active participation in the trend of large-scale art fairs?

At the end of the day, it’s all about the dissemination, understanding, and appreciation of artists’ books. So, if a large-scale art fairs offer us the chance to have a presence there, then it’s another step towards achieving that primary mission. These fairs have large audiences, and maybe even visitors who aren’t aware that their favorite artists featured on the walls of the fair also have publications on our table. So we see this as an opportunity to educate about and spark interest in artists’ books in a mainstream visual-art-world context.

(7)

Are there any program details of the 2015 fairs that you can share?

We’re still in the planning stages of a lot of the content, but one thing we’ve confirmed and are super excited about is the exhibition we’re planning for NYABF15—a retrospective of Paper Rad publications and ephemera.