Wickerham & Lomax

Wickerham & Lomax are a Baltimore-based collaborative started in 2009. Their practice is based on the accelerated exchange of frivolous information, gossip, and codified language that crystallizes into accessible forms in hopes of giving dignity to that exchange. Recently, they appeared at NADA NY with American Medium, where they will be exhibiting in September.

In this roundtable discussion, they field questions from Petra Cortright (artist), Ginevra Shay (Program Manager at The Contemporary), Eliot Glass (promoter), Daniel Wallace (Co-Director at American Medium), Kentrell Searles (muse and cast member), Amelia Szpiech & Hunter Bradley (Owners of Springsteen Gallery), Ilia Ovechkin (artist and filmmaker), and Sebastian Demian (gallerist).

Petra Cortright: What is a typical day like for you?

Malcolm: Fully digital morning, engrossed in the soup of social media and blogs. An hour to hour-and-a-half gym session for my body before my brain is swamped by emails and the studio. Then I'll make lunch, avoiding all of my “It's Complicated” vegan options. And in between every head/heartache, a cigarette. Then I'll set myself up to work on projects till exhaustion.

Daniel: It starts with coffee and ends with vodka. The middle is sprinkled with cigarette breaks at the studio or on the front porch between Blender render sessions. Each day is spent punishing myself for playing God.

Petra Cortright: Do you have any beauty secrets you would like to share?

M: I have this one beauty secret. I've been hiding it from this guy that frequents a local bar here in Baltimore. It makes your skin taste amazing. If delicious is the aesthetic paramount for taste then somehow this is a beauty secret. I don't know if everyone wants to hear, "You taste really great," but I do.

D: Yes! Don't have our typical day.

Ginevra Shay: Your working methods are pretty mysterious. I know you do a lot of research, planning, writing, thinking. You're always in the studio. At what point do you decide what the work will be? What thresholds/borders do you think about? At what point are things fluid/expansive? At what point are they compartmentalized?

M: I think Daniel and I still believe in something quite old fashioned, which is mystique. I try to withhold new work from being posted or shown online until it's actually finished. Then I seldom put anything up unless it’s a highly removed supplemental. I think the work's general form or makings come to us in a flash we know all at once, and then the particulars are trial and error. This is when it’s expansive. The thing that usually stops a work from coming to fruition is feasibility: Can we make a lightweight wall work out of a metal that can hold magnetic gossip? Can the window for people's browsers fully be a circle instead of a rectangle? Will this bulletproof glass be able to have printing in its cracks?

Petra Cortright: What do you like about living and working in Baltimore?

M: The lack of business cards one receives and the extreme reality distortion that happens on a daily basis.

D: New Yorkers think you made a mistake.

Eliot Glass: Given the socioeconomic climate of Baltimore, and its racially polarized "self," in what ways do you feel that maintaining this base informs the nature/topical matter of your work?

M: Baltimore is this common ground from which we both can speak. A space that we both can negotiate in a very present and in-the-moment way through engaging certain realities and politics. In a sense it creates this erasure of our past, even though part of our understanding of the city is filtered through this past. Choosing Baltimore as a base is important because every place needs vigilant human resources to speak of their present—creative or otherwise.

Petra Cortright: What food do you like to eat while making work?

D: I like this question because it assumes we have choices. Our studio is located in what has been called a food desert. And they’re not wrong. On the chance encounter of an oasis I hope to find Doritos and Zebra Cakes.

M: I would prefer to eat what Daniel eats which is nothing but a cute donut with bacon. That sounds good... and candy—tons of candy.

Petra Cortright: What do you do to take care of yourselves?

D: Seeing Malcolm is good for the soul. If I stop working, everything dims, so I keep working.

M: I typically recall the last time I cried. It’s a question I ask myself every so often. When was the last time you actually cried versus wanting to cry? I think it helps to keep my humanity open, and it allows me to really sync myself with the world.

Daniel Wallace: This is more about the two of you than the work, I find people are curious about how collaboration, especially over such a long span of time, (since 2009?) functions. What is the process you all have developed? Is there collaboration without consensus? Do things ever get competitive? How does compromise affect the final outcome? For instance, in the work I wanna steal your shit, I wanna take your vision, Where did the idea for the purse come from? Are both of you taking turns adding images and objects to the work? Is the image traded back and forth or are decisions made in collaboration and then the painting gets executed by one of you? Are each of the paintings in the recent series made in the same way as the next?

M: The creative vision is carefully curated beforehand as we move towards execution. There may be a point in the continuum of production that we stop the execution process to reevaluate, but we do it together. Even if we work on separate CGI components, we know how they have to nest themselves back into the framework we've established through the checks and balances implied by the ideas.

Petra Cortright: Do you consider yourself busy people?

D: It’s been our guiding principle. Keep working, let them decide if it’s good or not.

M: I always want to be less busy, but I find so little satisfaction in it. I took a week off to just think about the next show and I felt miserable and empty. I have this farm boy mentality, that if you aren't busy, there's no spectrum; you're just lazy—which is harsh and unforgiving and will probably result in some form of Mariah Carey's Glitter exhaustion in 3–4 years.

Ginevra Shay: I know that in some of your work is the creating of seasons/series. Could you talk about that? Do you ever feel like you’re directors of a world that you're building?

D: Seasons and series were the obvious way to split up bodies of work that are involved in telling a long narrative the way TV shows like The Wire work with storytelling. We are using TV as a form to create a network of information by focusing on the forms supplementals. We have focused on dissolving the distinction between roles of character, actor, author, and fan. It’s like trying to be all the eyewitnesses at a crime scene. Nothing adds up and everyone thinks they saw what happened.

Sebastian Demian: What can the BOY’Dega universe tell us about our future? What advice can the cast give us about how to proceed?

D: Nothing overtly will be learned from the cast—maybe as much can be learned from a TED Talk, but when engaging in the BOY'D world of choice and navigation, a viewer is reminded not of a goal-orientated system but of the mere present.

Daniel Wallace: The video, sculpture, and print are all coming out of what you have called "world building." The quality inherent in digital renders leads one to find links to fantasy and escape, relative to gaming and animation—both often associated with being youthful and, at worst, frivolous. While some elements in your work are certainly fantastic or "unreal," others are truthful representations of "real" spaces, objects, people, and events. How does the conflation of the fantastic and representational become a critical tool in the work across the various media used to visualize your world?

D: The manner in which the work is presented becomes a way to inform the fiction of these items, to provide them with a logic structure that could lead towards reality. The "fantastic" is the real in the world we build. I think the criticality falls somewhere outside of this conflation between real and fantastic.

Ginevra Shay: How do you approach editing and authorship in your work?

D: Editing is additive with the attempt at refinement, but subtraction is not usually in the equation. We live in each other's brains intimately. I think it takes great trust to share equally in a vision. Authorship is also a subject in the work because we have an ensemble cast that authors the experience of our main character BOY'D, who essentially is a ghost.

Amelia Szpiech & Hunter Bradley: Your exhibitions are always super involved presentations that are layered with image, material, and language. At this point, you have definitely created your own language and methodology that is consistent and specifically yours, using recurring themes like abundance and conflation. Can you talk about these methods of communication, or any others that you intentionally utilize in your practice?

D: As I’ve said, we've been trying to take the supplementals of a TV show and allow them to be centrally located or to stay marginalized with greater dignity. Our world building exists online through the BOY'Dega web project to allow viewers full-time access to its evolution. Each addition is meant to add + stretch that world, to undermine its own previously established language and to reinforce its previous position. Each new show is an opportunity to rewrite the codes so that the viewer is really placed between bodies of work, negotiating the shifts presented. The idea is a mutation over the course of generations (or bodies of work).

Amelia Szpiech & Hunter Bradley: In your show with us, Girth Proof Vol. II, and throughout your practice in general, you consistently use your friends and intimate social circles as subjects. Can you talk more about how they inform the work, what role they play, or what you find most crucial about them?

D: We use Baltimore as a material, and its ready-made characters we try to splice with fictions.

M: We tend to utilize the intimacy and those places of exchange as a device in the work. Those things go through distortions to segue our friends and social circle into a kind of raw material that can be exported or sent out into the world. What we want people to know is the value of the people we've selected and their ability to generate various plausible narratives. We tend to leave their characterization or representation at an open-ended state, not aiming to over-determine them, because we're working under this idea that the whole city is a medium. As tastemakers they’re all fluidly extending themselves into others.

Sebastian Demian: What kind of feedback are you getting from the people regarding your latest works at Terrault Contemporary?

M: The feedback is mostly shock. I think people have this expectation that we will always do installations. That there will be some small object that wouldn’t sustain its legitimacy of being art in another context, and with this show we shitted on that. We wanted to make paintings in the way we knew would work for us as people. We loved gagging them on their own logic. But people love paintings—which we’ve always known—and people like these works.

Kentrell Searles : Is there any specific event or relationship—doesn't have to be romantic—that resonates with you as the source behind your recent work? There's a lot of sexual innuendoes and moments of almost fetish-like references. Is that something you're interested in, or is it actual events/men you've encountered?

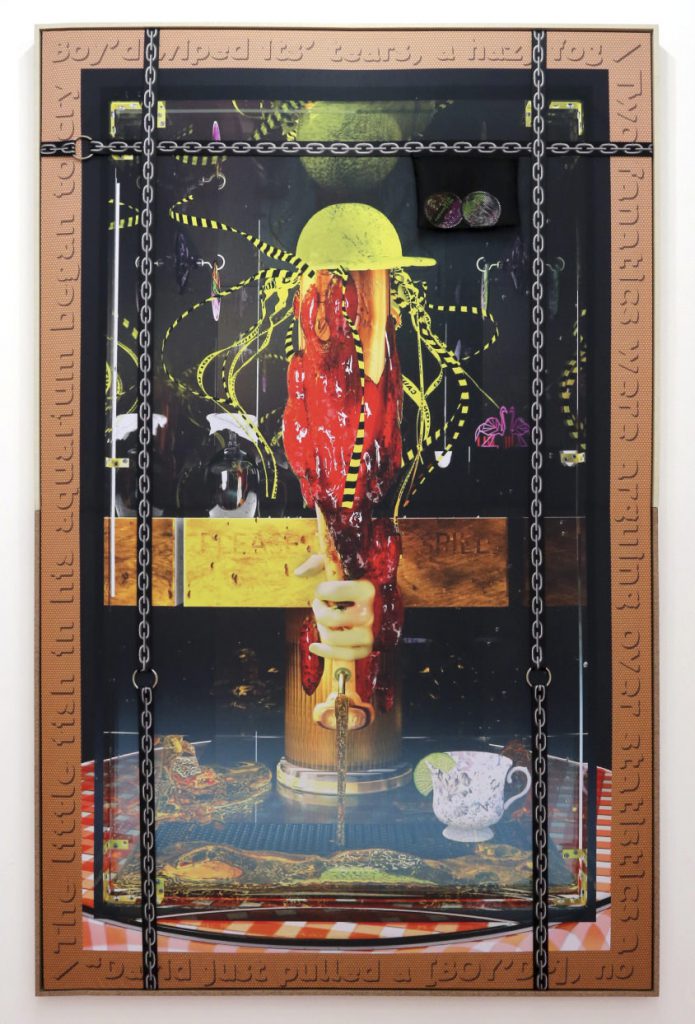

D: (Referring to the Uncool show) The empty coin purses with charms? The deflated Roman column? The beer tap flowing with yellow piss? The butt purses? The dildo that looks like an Angler fish? A glass chest filled with earrings? What innuendoes are you speaking of? (laughs) The only hard-and-fast rule for these paintings were that they had to be in vitrines. This created a window context or storefront vibe that could feel voyeuristic. When you put a girl in a box, make sure you shine a spotlight on her. That might have been erotic tension. In the past we've aligned ourselves with subcultures not our own and used their clichés like mesh and body hair to address (or undress) them.

Amelia Szpiech & Hunter Bradley: To build on our last question, you've also included references in your work to fraternities and other types of social groups that you aren't necessarily involved with. It seems there's something about the way people self organize or identify that has always been present. What is it about these tendencies that interested you?

M: We are interested in the coded languages these groups develop, the social spaces they share, the intimacy that is seldom shown of these groups because they typically get turned into a finite set of images and practices. What we want to do is have the individual and the group influx to push towards a third, seemingly out-of-control thing but hopefully present an insightful proposition.

Daniel Wallace: While the narrative you are constructing is convoluted and sometimes confusing, it seems like it is very important that it finds its way into the work in very concrete ways. The language both in the videos and found in the recent paintings are at times incredibly revealing and honest and other times, much more like poems, or strange translations. How do you see the use of language functioning in the work? How much is the text meant to illuminate? Is there a conceptual function to having the text shift between exposition and abstraction?

M: We think of narrative in our work not as building stories but as an exploration of its various components and devices. We are using as a metaphor the dismissal of the central narrative for its surrounding attributes to talk about a city like Baltimore, flanked by the “US cultural capital” of New York and “US political capital” of Washington, DC (this is a generalization). We aren't trying to confuse the viewer through the various forms of language or modes of speaking but trying to have the maximalist approach of the visual not be overly articulated by didactic text. We want them to seem to live in the same invented space, distant and familiar all at once. There is a shift in the language to challenge the singular voice.

Sebastian Demian: Have you seen any of your radical design ideas adopted in real life by others in any way? Or do you have any intention of making these worlds or more of their constituent parts physical for the audience—in the way you're bringing the belts and the handbags to life in your recent work?

M: I think the ideas and presentation have this density that makes them difficult to co-opt. I think some of the newer works, which are object-based, will be easy to take visual themes and details from, which is part of the legacy and life of any image. We are moving towards physical shows in tandem with the website moving forward, so the vision begins to become more clear for a viewer.

Ilia Ovechkin: Is there a gay mafia?

D: There is a gay Baltimore gang called the Pink Stars. And another one called The Dolls. I see them out a lot.

M: If we agree on the term, yes. And if we don't agree, yes.

Petra Cortright: Describe your dream studio.

D: Ideal situations are never good for artists. But in an ideal situation, the speed of production would match the speed of our ideas.

M: Oh my god! Now this is the question! First-floor studio, huge windows, garden out back (cute but not quaint), and some way it can morph into a private jet or yacht. It also would be great to function as a fashion atelier; we've become more interested in using those techniques for producing objects moving forward. Actually, any place I can work with Dan is a dream.

Ilia Ovechkin: What is the best/worst purchase you've ever made?

D: These highly powered computers for rendering/These highly powered computers for rendering.

M: An arts education.

Petra Cortright: What do you do to relax?

D: I'ma Read

M: To relax? I don't know what that is and I find it suspicious. This is definitely not a Baltimorean question.

Ilia Ovechkin: Do you remember a specific time you had an epiphany?

D: No.

M: Whenever I dream about celebrities, I wake up with a bestowed sense of knowing.

I dreamt about Anna Nicole Smith, and through my experience with her, I knew so much about fallopian tubes when I awoke. I don't recall knowing much about fallopian tubes prior. Maybe these dreams are kinds of epiphanies—knowledge culled out of thin air.

Petra Cortright: What breed of dog do you most identify with?

D: The ones at the top of my feed. Magnet @projectlamar

M: I love animated dogs. I identify with their hope of trying to fully embody "the real."

Petra Cortright: Describe your dream life?

D: Don't let them write the pages of history without you. To make a worthy contribution with humility and grace (which also happen to be my two drag names).

M: I'm a romantic in certain ways, so my dream life is to be boundless and fully adaptable. I'm trying to avoid articulating this in a way that leans towards materiality (homes, clothing, trips, and social cachet). I'm trying to make sure my dream life is something that's carried in my personhood. Something I'm never without. I remember this girl being really shocked that a black guy could answer chemistry questions in our high school groups that she could not, and it’s primarily been my aspiration to stunt on people who I never wanted validation from in the first place. I'm working on the ego, but I'm living in the dream.