Barney Bubbles

Text by Ben McKernan & Vanessa Nunes

Barney Bubbles (b. 1942 - d. 1983), was one of the key figures in design world during the 70’s and 80’s creating both beautiful and original albums covers that had a huge influence on how people thought about album art. In spite of his prolific output, he managed to remain both illusive and enigmatic throughout his career. One reason for this was that design in the music business was still in it’s its formative years and its influence and significance had really not been established yet. Today a medium all in its own, design itself lacked a sense of ‘history’ and narrative. But Barney Bubbles is also to be held somewhat accountable: not only did he refuse to sign his work, his name was another way for him to underline his desire for anonymity. Born as Colin Fulcher, Barney assumed his alter ego whilst traveling and working in San Francisco in the late 60’s creating psychedelic light shows using bubbles.

After studying at Twickenham College of Art, Colin Fulcher landed a job at the then prestigious Conran Design Group in 1965. At 23 years old, he cut his teeth at projects like the catalogue for the Habitat homeware stores and the D&AD exhibitions. In spite of a bright future in commercial design, Fulcher left all that behind to join London’s underground scene.

He started to collaborate with indie magazines Oz and Friends (later Frendz). Existence is Happiness, the foldout poster that Bubbles designed for Oz’s 12th issue (1968), shows bold blocks of color together with highly decorative images. An example of his love of appropriation and reinterpretation brings together influences of Pop Art as well as Art Nouveau.

It was during this period that Bubbles met Hawkwind, for whom he designed the cover for In Search of Space (1971). Although this early work is to be considered a precursor to his more influential post-punk design, In search of Space is a masterpiece of what can be termed a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, or a total work of art. A hawk-shaped, two dimensional spaceship design that opens to reveal a poster layout with the band’s portraits. It was an amazingly ambitious design. Although the general concept for the album art came from Hawkwind, they gave Bubbles full freedom, and he acted upon it by taking control over the band’s visuals, applying his motifs everywhere from their communications materials to their equipment. Unrestricted by the physical space of the record sleeve, he created a cohesive and unified picture that translated the bands own mythology.

Bubbles moved to Ireland around 1976 and took this opportunity to fill in the gaps of his Art History education by researching early twentieth-century art. Constructivism, Cubism, Dada, and anything else that caught his attention became a part of a renovated visual vocabulary.

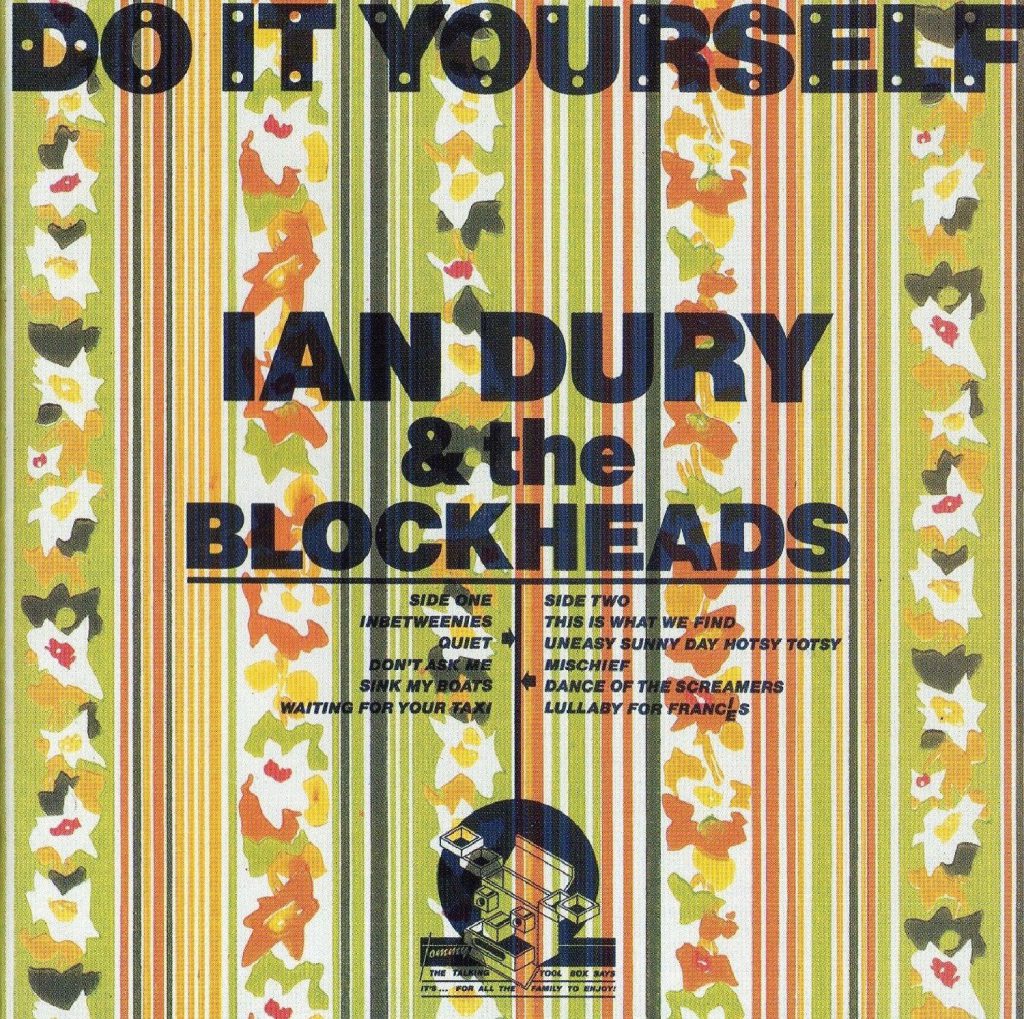

Jake Riviera, a friend and co-founder of Stiff Records, begged him to return to London and offered him total control over his bands’ image. Bubbles was to follow him from Stiff to Radar and later on to F-Beat, always creating original artwork that had a perfect match in Post-punk’s urgency. In this setting Bubbles found a new home, leaving his hippie days behind and embracing the post punk scene.

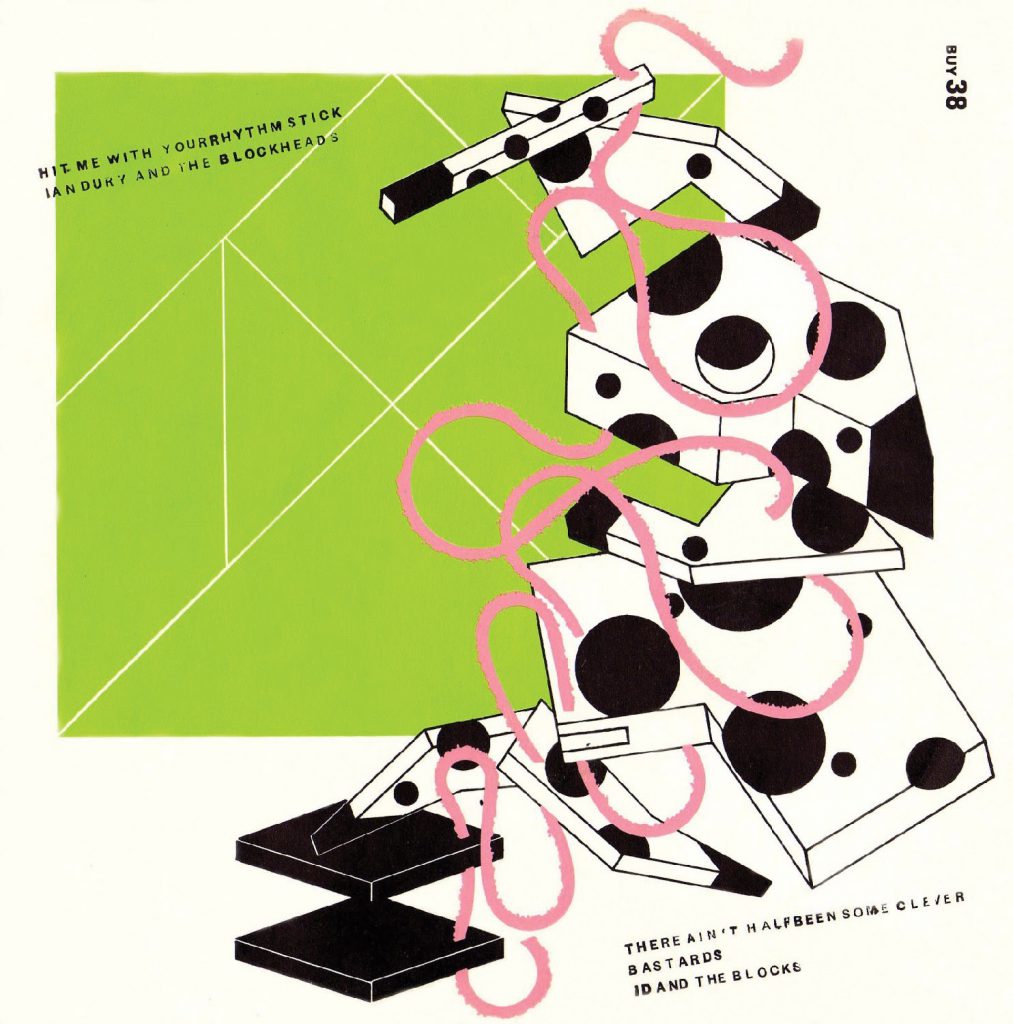

The Damned’s 1977 album Music for Pleasure is an appropriation of Kandinsky with hidden portraits of the band members, while Generation X’s Your Generation makes a direct reference to the work of El-Lissitzky. Elvis Costello’s 1978 album This Year’s Model plays with design’s work process by showing CMYK color bars and an apparent misprint of the album’s name. There is a lack of preciousness and an energetic eclecticism that characterizes Bubbles designs. Not recognizing boundaries between high and low culture and always trying to merge them allowed him to avoid being pigeonholed, as was the case for many successful designers.

Looking back at Bubbles career, it is hard to understand why he did not wish to be recognized. Although the fans knew the covers, they were most likely unaware of the man behind these. A rare interview published in 1981 in The Face magazine sheds some light over the subject with Bubbles displaying a strong sense of professional ethics. As a designer he saw himself as an interpreter of his clients wishes: “I feel really strongly about what I do, that it is for other people, that’s why I don’t really like crediting myself on people’s albums – like you’ve got a Nick Lowe album, it’s a NICK LOWE’s album not a Barney Bubbles album!” When asked about the attitude of young designers who saw their work as Art, Bubbles expressed nothing but disappointment. “All that to me is highly suspect because you’ve got to wait, hear the music and meet the guys, and they tell you what they want and then it’s up to you to deliver that.”

In the last few years of his life, he did less and less work as a graphic designer and committed more time to working as an artist and painter. In his final years he had spent some time dealing with a nervous disorder and finally, in 1983, at 41 years old, Barney Bubbles decided to end his life. In many ways Bubbles modesty was a double-edged sword that allowed him to perpetually grow as a designer without getting pompous and never stale. Yet, it was also this modesty that allowed him to completely under sell and under promote himself and so allowing his contemporaries to take center stage.

With more recent attempts at wider recognition, his work has been included in exhibitions and retrospectives, press coverage and a book (Reasons to be Cheerful: The Life & Work of Barney Bubbles, Adelita, 2008). Although Barney Bubbles went to great lengths to make himself anonymous, we can see today how his designs keep influencing new waves of young designers.