Gaspar Noé

HS: When I saw Enter The Void, I unfortunately saw it from the very first row in a movie theatre and I went to a bar after and ran straight into Nathan Brown who I knew—at the time—through mutual friends. The film was such an immersive experience that I remember seeing him and just being like, “Thank god, you’re okay.”

GN: I met him maybe 20 days before we started shooting. And two weeks before that, I introduced him to Paz and then I came back to Paris. Then, it was one week before shooting that I proposed to him to be in the movie. He had no agent, of course; he was working, selling t-shirts at American Apparel in Brooklyn. But he said, “Okay, I’ll do it, I’ll come.” Then he told his boss, “Well… I’m the star in a movie shot in Japan.” (Laughs) And—for sure—the guy thought, “What’s this bullshit? Stop lying to me.”

HS: Yeah, Nathan was not really an actor before that so I was curious about your relationship to actors or your relationship to acting in general and why you choose to sometimes work with people that don’t have any acting experience.

GN: I would say—in the case of Enter The Void—I knew that I would have problems if I ever proposed the main part to a professional actor or a wannabe actor because, with the main character, we see all the film through his point of view as a POV through his eyes. During the POV shots, Nathan was not holding the camera but it was me doing it. But he was sometimes behind me to answer to the other characters that were in front of the camera. Then, during the flashback scenes, the camera follows the main character from the back of his neck. And any actor who would have wanted to succeed in the film industry by showing his face onscreen would have been seriously frustrated (most of them are very narcissistic). So—since the beginning—I knew I should not consider casting an actor for that main part of the movie: I needed someone charismatic who would want to become a director or an editor. When I met Nathan, he said that he wanted to direct music videos. So I said, “Oh okay, I’m going to propose to you an accelerated film school course: you’re going to be the actor in a movie filmed from the back of your head.” (Laughs)

HS: How do you first conceive of a project?

GN: Sometimes images are the thing that comes first. Sometimes they’re memories, sometimes it’s a crime story you read in a newspaper, sometimes it’s a book you read or some old film or documentary you’ve seen. As most directors, I briefly thought of doing remakes of some movies from the 60s or 70s. In this case, it’s easier to feel self-confident; you know what you liked in the movie and what you did not like in it. And you replace those weak parts by something that is going to be stronger.

For example, right now, I’m watching documentaries all the time and I know that I want to do a documentary even if I haven’t found the subject. But I know which kind of documentaries are interesting me and which ones are more playful than others and which ones mix real footage with recreated footage.

HS: I had actually planned to ask you if you ever considered doing documentary films.

GN: Yeah. Also, the good thing with documentaries is that you have fun doing the research. You have fun shooting the images... And you can also have fun reinventing what existed but hadn’t been filmed; you use special effects or handmade photomontage or whatever. True stories are in many ways more touching than recreated stories and if, on top, you want to add music onto footage of real violence or whatever else, of course you can do that. You can use all the tools of narrative or experimental cinema.

HS: The reason I was planning to ask you that actually has something to do with the sense of truth you hint at in your films. You know, you have this 10-minute rape scene with Irreversible or a 10-minute sex scene in Love. These things are sustained and in real time, so I had wondered if you had an interest in capturing reality. For me, I don’t necessarily view your films as shocking or pornographic, etc. Instead, there is something honest about them. You hint at honesty a lot of the time, even with improvised dialogue or the desire to look at true emotion within in a constructed world.

GN: Yeah, probably I was raised (in the 70s) in a context that was much more open-minded than nowadays. When I would watch French TV at the age of 14, they were playing Taxi Driver, Deliverance or The Night Porter at 8:30pm on a state channel. And there were also all these erotic movies playing in theaters. Even if you were underage, you could still catch them in one way or another.

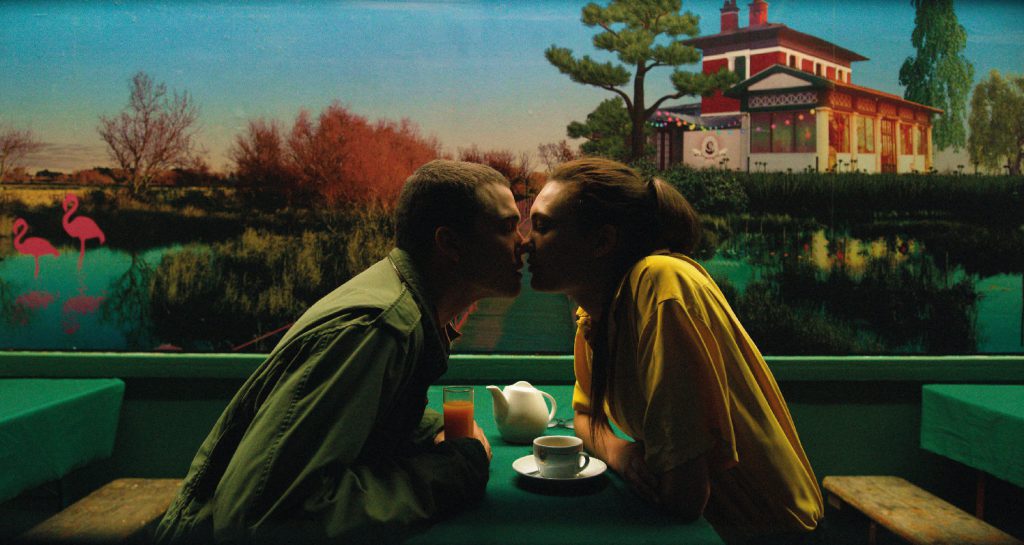

Also, there is one thing. For example, in my last movie, there were no love scenes that seem far from what relationships are in real life. I never wanted to do a pornographic movie. I just wanted to do a movie with a 70s feeling containing the kind of moments from life that my friends or I enjoyed or suffered. When it comes to the shocking images I’ve done, certainly the film people think most about is Irreversible. In that case, I wanted to do a violent, kind of retro movie. But also the whole movie, in many ways, was kind of a joke. I was doing a conceptual B-movie, a kind of mix of Harold Pinter and Death Wish. I never pretended I was doing a serious movie. Probably my last movie, Love, is far more serious.

HS: I read the interview you did for Twitch. In the interview, they ask you a couple questions and, in your responses, you give a great description of love. You also say that you had just wanted to do an honest movie on a central subject, which is being in love and what it’s like to be in love.

GN: I would say the movie is about falling in love, not love because falling in love is the first part of a long process. Sometimes when you meet someone—for a few years—you can be madly in love with. But then—once you get used to the person—it switches into something more brotherly. More quiet. You have more empathy. You’re less desperate to possess the person and you’re less desperate to want that the other person to want to possess you. Being in love is a situation that is very exhausting on an everyday scale. You cannot be in that love-passion for more than two or three years without screwing your whole life around. So what happens in a best-case scenario is that it switches to a more calm form of love, with kids or without kids, with an apartment or with other common projects of all kinds. But that crazy fever that sometimes burns during the very first period is very exhausting.

HS: You describe it as an altered state.

GN: Yeah. (Laughs) It can turn into a hardcore, but all-natural drug. There was a funny thing about my movie: I don’t think many people really got aroused during the screening but many, many people told me that they cried watching the movie and that they felt like getting into a love story again. You know, we all have been love junkies... All people that I know, including myself; we all have sentimental scars that still hurt when you reconsider them.

There many are books (like Hellen Fisher’s) about the chemistry of love and all the molecules that your brain produces when falling in love, the additional amounts of serotonin and endorphins. It’s like a natural drug; your brain makes up a natural mix of heroin, ecstasy and cocaine. You fall in love and you’re obsessed with one person and vice versa. It’s not a natural state of the mind or of existence. Hopefully, after a long while, you can switch that unusual molecular balance to something closer to everyday’s perception.

HS: Were you intending to make such a melancholic film with Love or did you originally intend for it to be a film about only intimacy that then naturally became what it was with improvisation.

GN: Actually- everybody is always raving about In the Realm of the Senses, saying, “It’s the best art movie containing love scenes,” etc. And it’s a good movie but I never enjoyed the fact that it ended with an act of violence and the girl cuts the dick off the guy. That was not relatable at all to my own perception of what sex is and what love is. That was a strange case of a movie that was shown on French TV all the time although it was very violent, probably because of the castration of the male character. In my case, this time I wanted to do a movie without any scenes of physical violence.

I was very surprised by some reactions to my last film. Probably the most puritanical reactions people had to my movie were coming from Anglo-Saxon countries in which people often ask me, “Why did you need to show a penis?” as if there was a problem with showing a dick. I very seriously don’t see what’s dirtier in a dick than there is in a hand or in a face.

HS: Why did you choose to experiment with 3D for Love?

GN: I guess there is something playful and intimate with 3D because you pretend that you’re making something that is closer to life and then, at the same time, you know that it’s not. That whole vision—you have to recreate the depth, the space… You have to perceive it with artificial glasses if you go to see it in the cinema or if you’re watching it on a TV screen. But, still, there is something weird about what comes out that makes it different from flat images.

When you see them talking from above, it just gives it the feeling that it is more intimate than a flat image. What I heard from people that were attending the movie in the movie theatre is that putting the glasses on makes you disconnect form the people that are around you because you’re more focused on the screen. For example, for its American and English distributions, the movie was shown without subtitles and that space that 3D screens create is very much destroyed by having subtitles floating on the space. So, that’s one of the reasons why I also wanted to do it in English; I wanted to reach a bigger audience.

HS: I had read that you were originally going to make the film with Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel.

GN: At the very beginning, no… At the very beginning, I had said that I would shoot that movie in French, in 2D with a young unknown couple. But one night I ran into Vincent and he said, “What are you preparing?” And I was not yet able to put the money together to do Enter The Void—which was a very big project—so I told him I was going to do this erotic movie, or this cheap, sentimental movie, in Paris and he said, “Oh, you know, I’m free, Monica’s free, too.” And they were this magic couple of French cinema at the time. So he said, “Do you think we could do it?” And, at the time, they were much older than the characters I had in mind. But so what? I couldn’t resist trying to make it with Vincent and Monica. Why not? So we started looking for the money and we found producers that were willing to do a sentimental, erotic movie with Vincent and Monica, of course. We had the money on the table. But then they finally read the short script and they saw more clearly what the project was about so they said, “Sorry, we have something left in our lives and that’s our intimacy and we don’t want to overexpose it.”

And we did this other movie instead with the money that we had found for the project (which was called “Danger” at the time; it was not called “Love”)… We did Irreversible instead. And many years later, I thought I would restart this project with an unknown couple but I did not find the couple. But I ended up doing the movie with a boy and a girl that I found without going through the traditional casting process. I didn’t care if they were professional actors or not. What I cared the most about was that they’d be intelligent, daring and touching. The screen doesn’t lie about charisma. A very few have it and most people don’t. Sometimes, in movies mixing professional actors and unprofessional actors, you can tell immediately who’s who. Sometimes the mix doesn’t work and sometimes it absolutely works. In my last movie, I think they’re absolutely great.

HS: You wouldn’t be able to say whether you prefer working with professional actors or non-actors.

GN: No, you work with people. I was just watching a movie this week called Edvard Munch by Peter Watkins about Edward Munch, the Norwegian painter. All the faces are so incredible and not one of them had been an actor before. But they are all perfect in the movie. Even the main character was a young man that the director found. Acting in a movie is not like acting a theatre play on stage. That requires real memory, you need very particular skills to repeat every day of the week the same sentences and words over and over. In movies, it’s far easier to manage working with people who are not used to being in front of the camera. Once again, it’s very hard to create the charisma when it’s not there. And new faces of people found in real life are very often far more exciting than the faces you’re used to seeing onscreen.

HS: Was film what you always wanted to do or was there ever another path in your mind?

GN: When I was a kid, I was going to watch movies almost every day. I was also watching movies every night on TV. And I was reading comic books all the time. I was obsessed with Robert Crumb and some other comic book artists. But doing comics is a very lone experience. I don’t think I could be a writer or a comic book artist because you spend a lot of time alone in front of your pen or your computer… The good thing about arts like cinema is that they are created collectively and you enjoy sharing the experience with other people. Even if you are the director, the writer, or the producer of the movie—in the end—you know you’re just like the captain of a football team and if anyone in your team does not play properly, you lose the game. For sure, I enjoy the collective experiences more than the lone experiences.

HS: Can you cite any films as inspiration from when you were growing up that you maybe still hold as influences today?

GN: I guess the first movie that really impressed me was when I was maybe four-years-old. I saw Jason and the Argonauts on TV when my parents were living in New York and the vision of skeletons fighting with swords in a Greek temple screwed my mind. Then, when I was seven, I saw—on a big screen in Buenos Aires—2001: A Space Odyssey and I’ve seen that movie every year—or every two years—since. That was the shifting point that made me want to become a director. The next one was probably Eraserhead- that, I saw when I was 15. At 18, I saw Deliverance and Pasolini’s Salo.

HS: You’re from Argentina. Why did you come to France?

GN: My parents had to move for political reasons because they were both left-wing and it was a dictatorship and some of their friends were disappearing in torture camps. It was much safer to escape than to stay.

HS: And you ended up in film school in France?

GN: Well, at first I went to secondary school then to a film school. I finished my film school at the age of 19 and then I went to study philosophy for two years but I was not very focused on that.

HS: I also studied film in school. I just found it to be so hard to financially stay afloat while you try to come up with funding for projects.

GN: I would say now what makes things easier for the new generations is that you can really shoot with cameras that are very cheap—and with the cards you can reload all the time so you don’t have to buy negative film stock. You don’t have to pay the lab for every image that you want to turn into a positive image. You don’t have those negative splices that make the movie that could be projected onto screen… What I remember when I did my first feature is that probably 40% of the money that I was spending on the movie was dedicated to the Kodak film stock at the lab and I had to borrow an editing room, etc. So now, you can do all that with your computer and your Canon 5D camera and there are some movies that are absolutely great that are shot with no money at all. Even the cheapest movies from the 50s or 60s are not as cheap as the ones you can make today.

HS: Have you ever studied acting at all?

GN: No, no. I just went to film school for camera operating. I’m very obsessed with the image; I operate the camera all the time. But I let my cinematographers hold the lighting, etc., because you cannot be focused on the project or the lights and the actors at the same time. It’s too much work.

HS: Are there any unifying themes in your films that you see yourself coming back to a lot?

GN: There are many red tunnels in my movies; they come over and over. Then there are often unlucky, pregnant female characters; maybe there’s a fear of paternity. There is a very animal perception of the human kind. And there is some artistic need or intention to build my movies out of a structural concept.

HS: Do you enjoy watching more conceptual films personally?

GN: No. But if the structure of the movie is too conventional, I get bored-in-advance as a viewer. And also, as a director, you’re more excited to go to the set when you know you’re trying something that is different—or at least partly different—and not something you’ve seen before.