Larissa Lockshin

Text by Antonia Marsh

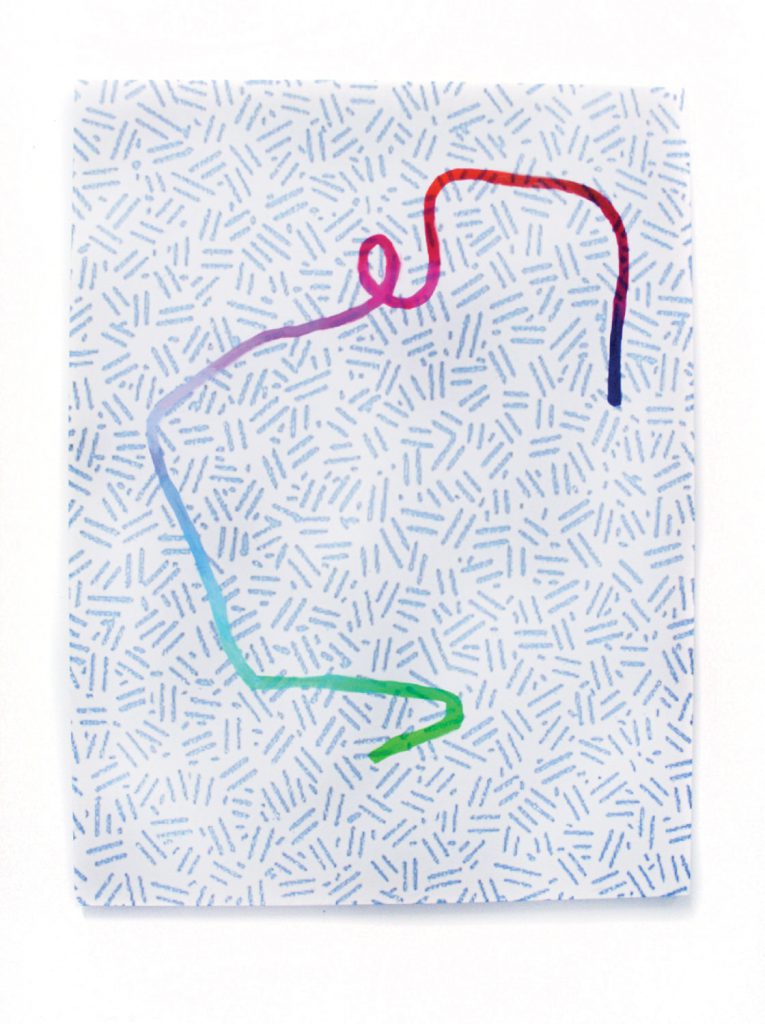

Arriving at recent Parson-graduate Larissa Lockshin’s live-work studio, little abstract paintings are stacked by size from right-to-left along a white wall-edge. While Lockshin’s practice might be restricted to painting, her choice of medium resists limitation. From colorful outbursts of wholesale printer ink, to crushed mica, acrylic, oil stick, latex paint, enamel, and chalk, her canvases contain a cacophony of sugary color. Incorporating a multitude of materials, she sheds the dated connotation that might accompany one material or another, allowing Lockshin to reach closer to her abstract objectives.

By framing her paintings either only on two opposite sides of the canvas, or with painted wood, Lockshin furthers her attempts to separate her artwork from sustaining what she believes to be a limiting categorization as purely painting. Founded out of a frustration with the emphasis in her undergraduate years at art school on performance and conceptual art, Lockshin insists that creating objects remains a prodigious priority. Not just images hung onto a wall, Lockshin’s canvases reach outward and exist in the liminal space situated between painting and sculpture. Lockshin maintains her concern to create paintings that can exist as objects, and not just vessels for pictorial content. If, therefore, a wall-based artwork is to exist as an object in this way, does this collapse a distinction between painting and sculpture, or even suggest its ultimate futility? When asked to what extent she feels this distinction remains valid, Lockshin responds that while the art market still demands a distinction, perhaps brought about by a loss of the context in which an artwork exists brought on by image-sharing platforms; in relation to her practice, the distinction remains defunct.

Freeing her work from the pictorial constraints of painting, exhibition in the gallery space emphasizes the object-hood of Lockshin’s artworks; separated from the walls either suspended from the ceiling or freestanding. Deliberately devoid of particular content, Lockshin’s abstractions therefore exist in their own context as their own individual units of display. The decision to delve into abstraction stems from a conviction that the extreme over-abundance of images we are confronted with in quotidian visual culture drains any value from the image itself. Consequently, in her attempts to raise the object value of her paintings, Lockshin chose to distance her works as far from a recognizable image as possible. Replacing image content with object-hood as her major priority signifies an attempt to frustrate the viewer, a response reflected in Lockshin’s dissatisfaction with the perpetual conundrum for artists working since the Internet: how can artworks maintain value as physical objects rather than through their image content when they are most often viewed online? As if by mirroring the behavioral tropes of an image online might provide some kind of catharsis towards this problem, Lockshin insists that she seeks to create works outside of any context whatsoever.

Aside from these object-paintings, Lockshin continually collaborates with artist and friend Georgia Cronin on a series of latch-hook rugs. Varying in size and suspended on the wall either framed or unframed, these furry entities are the result of extended, almost torturous twenty-hour-plus sessions over numerous months, of hooking wool thread through netting. While this endurance denotes a feeling of discomfort in any viewer, the contrast of this emotion with the irresistible desire to stroke each tactile achievement is perplexing to say the least. As if through naïve wonder when faced with the largest rug piece, I instinctively turn a corner over to reveal the side flush with the wall, a state that apparently was considered a potential method of display. Accompanied by a list of sentences the artists composed together while working, when read aloud alongside these rugs, it becomes easy to enter into a not dissimilar trance- like state to that Lockshin and Cronin found themselves in:

“The rugs are about silence. The rugs are about time. The rugs are about intersections. The rugs are about connections. The rugs are about softness. The rugs are about hooking with purpose. The rugs are about sitting for an extended period of time. The rugs are about craft. The rugs are about journeys. The rugs are about learning... The rugs are about cutting strips, controlling your physical movement. The rugs are about reaching down and smoothing over. The rugs are about aging. The rugs are about making your eyes hurt.”

The repetitive nature of this text, twinned with the recurring action of hooking each piece of thread through becomes almost performative, as if chanting a mantra or manifesto qualifying their draining labor. As well as denoting the core aims of creating these rugs, The List equally makes evident precisely what the works are not about. Through the absence of engagement with certain discourses, namely theories of domesticity and female labor, it becomes clear that Lockshin and Cronin are deliberately avoiding association with the dated connotations that link craft and womanhood. When asked about these potential implications, Lockshin agrees that weaving can unfortunately prevail as an inherently female activity in the popular mindset, however the rug works enabled her to cathartically draw attention to this discrepancy precisely through their lack of engagement with it. The List chimes in: “The rugs are a question of artist or artisan, ” and this point remains crucial to Lockshin: what might be considered painting or sculpture for a male artist, might still be considered craft for a female artist. For Lockshin and Cronin, the difference between the art object and this craft object definitely lies in gen- der historically: an associative trope that requires imminent redefinition.

This desire to articulate her concerns through a definite clarity in what she rejects, ignores, and abandons, almost as if a conceptual process of elimination, recurs in the impetus behind Lockshin’s individual practice. Often beginning from a lucid awareness of how she does not intend her paintings (or objects) to exist, Lockshin seems to work backwards, where what began as limitations, become opportunities, and vice versa. What lingers after our visit is particularly clear: for Lockshin, exploring a balance between the material and technological limitations—whether related to the object-hood of a painting or the context in which it exists—propels her practice forward and into a realm where dated associations and categorizations are no longer useful or productive in defining an artist’s work. III